By Guanxiong Qi, Florida State University

On July 13th, 2021, with collaboration from the Frogbear project, Professors Imre Galambos (Cambridge University), a Dunhuang manuscript scholar, and Michelle C. Wang (Georgetown University), an art historian of the Silk Road and Buddhist art, together held a summer workshop on ninth- and tenth-century Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings with students from various academic disciplines and continents. After the introduction in the first two hours, Galambos and Wang each gave their lectures and held Q&A sessions. In the last hour, students were divided into six groups with different assigned images of manuscripts or banners to make some hands-on analyses, and received valuable feedback from the two professors.

Imre Galambos (Cambridge University) and Michelle C. Wang (Georgetown University). Screenshots courtesy of Carol Lee (UBC Frogbear). Republished with permission.

Before the start of their lectures, the two professors stated the goal of this workshop and raised some methodological concerns. By examining different formats of materials produced in the same period and the same cultural context, the workshop aimed to put manuscript studies and art history in dialogue from a multi-cultural perspective. By highlighting the relevance between the processes of making manuscripts and paintings, the workshop illustrated that these materials share certain common functions and practices, such as venerating gods and assisting the dead. With alerts on the limitations of source material, Wang emphasized the importance of having physical, instead of virtual, access to the objects of our studies, since color, size, textile, and many other aspects of the Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings cannot be fully inspected on our computer screens. Despite the current difficulty for international traveling, these materials are better examined in person rather than via online media. Galambos then briefly explained the textual approach to manuscript studies that previously dominated the field of Dunhuang Studies. Students need to be aware that earlier textual scholars typically only examine the text, inscription, or colophon of a manuscript or a painting to make their assessment and analyses of the object without paying any attention to their physical features, material aspects, and iconography. This workshop aimed to overcome some drawbacks of earlier scholarship, by developing new methodologies and approaches to the study of the Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings.

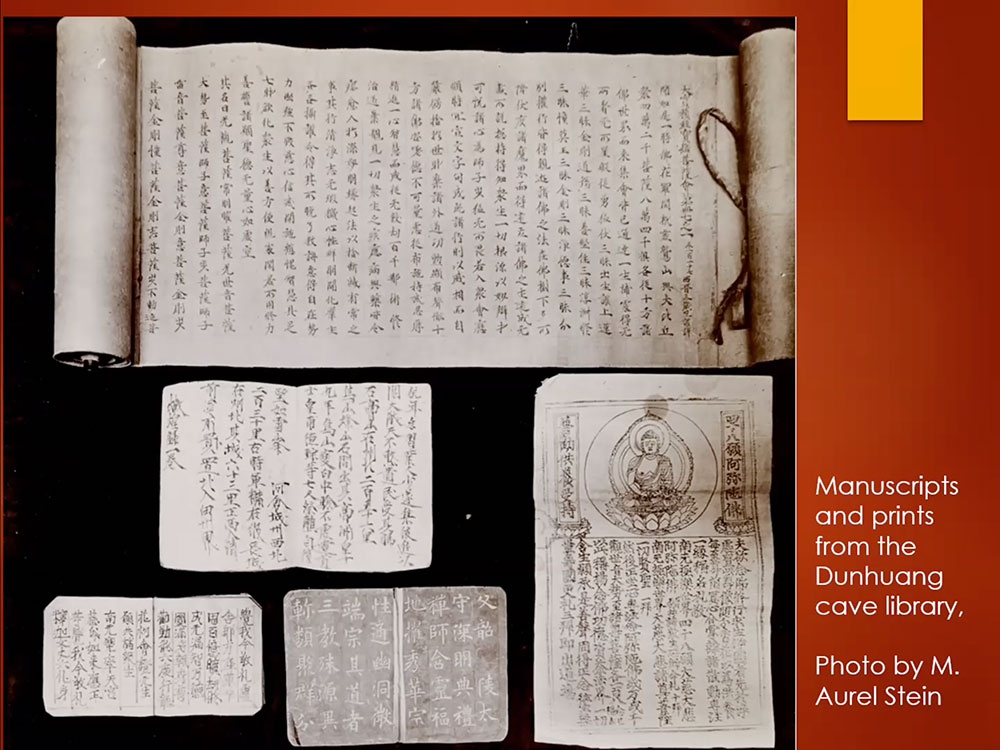

Galambos started his lecture with a brief introduction to the multi-cultural context of ninth- and tenth-century Dunhuang. The objects examined in this workshop were produced in Shazhou state 沙洲 during the Guiyijun 歸義軍 period (851–1036), which was nominally controlled by the ethnic Chinese states. In this period, Dunhuang was the place of cultural conversations and exchanges between different ethno-cultural groups, such as the Ganzhou Uighur, Xizhou Uighur, Tibetans, and Khotanese. The encounter with non-Chinese scribe culture gave rise to new forms of manuscripts. For example, the production and usage of concertina and codex booklet, instead of the traditionally Chinese-style scroll, represents the influence of non-Chinese cultures.

Various formats of manuscripts and prints from the Dunhuang cave library. © Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Cat. Stein LHAS Photo 13.1.75. Republished with permission.

Various formats of manuscripts and prints from the Dunhuang cave library. © Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Cat. Stein LHAS Photo 13.1.75. Republished with permission.

Therefore, scholars must consider the multi-lingual and multi-cultural context of ninth- and tenth-century Dunhuang to understand its religious objects. Galambos gave four methodological suggestions: 1) examine both text and manuscript; 2) focus on people and practices, rather than texts; 3) consider the entire collection; 4) look at them cross-culturally. First, scholars need to define and distinguish between text and manuscript. The manuscript is the physical and specific instance for the text. Scholars shall not only examine the content by analyzing the text but also pay attention to the physical manuscript. Second, the manuscript is used by people for religious activities and performances. In other words, the manuscript is the product of actual practices. We should attempt to understand their functionality, rather than treating manuscripts as mere objects. Third, regarding the early academic practices of the field—in which scholars pick interesting instances but ignore the larger context—we should consider the entire collection, to think about the formation of the Dunhuang collection and their function in total. Lastly, because of the disciplinary training of scholarship, people usually look at the manuscript only from one’s disciplinary perspective. For example, Sinologists would only examine the Chinese text of a manuscript and a Tibetan studies scholar may only study the Tibetan scripts. We should be aware that these manuscripts are produced together in a multi-lingual context, so we shall look at them cross-culturally.

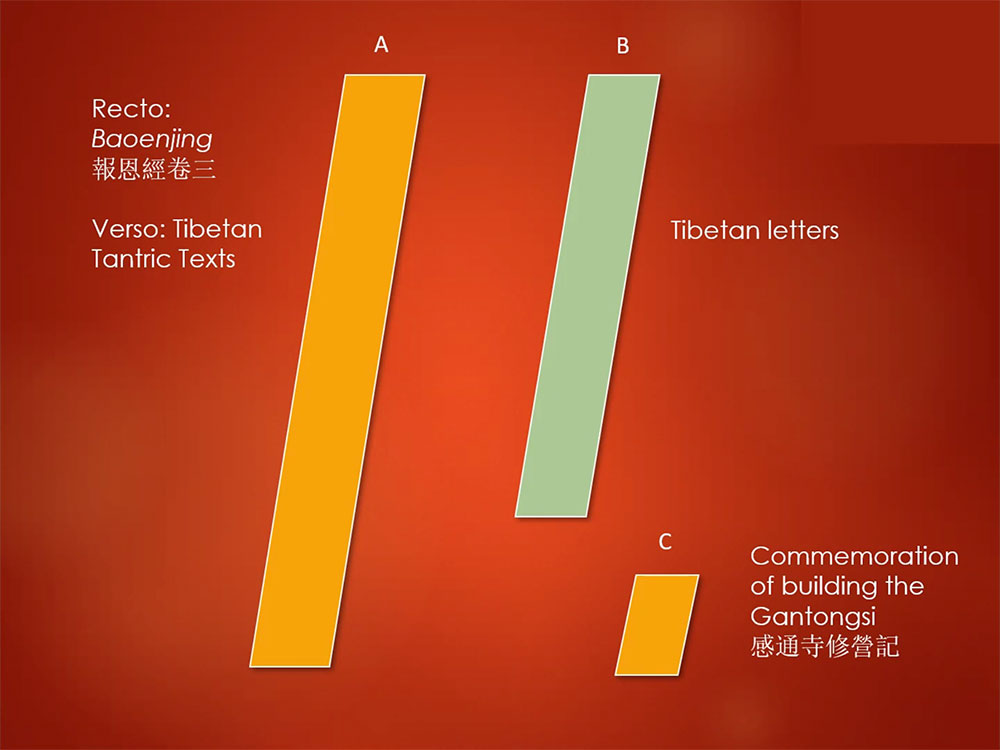

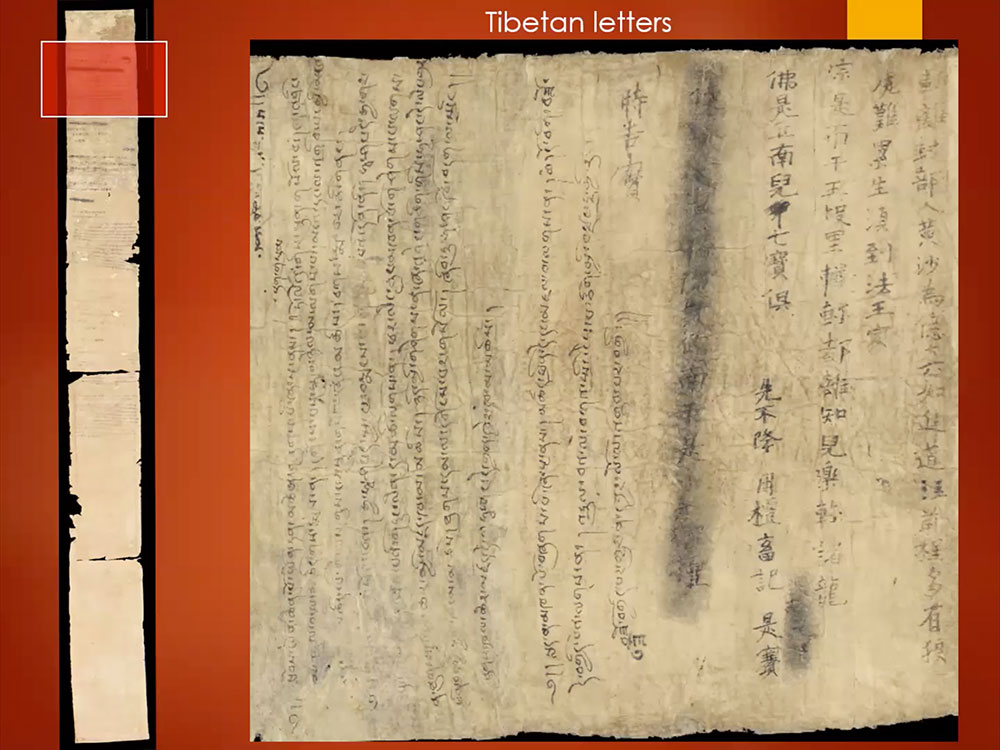

Galambos chose some manuscripts as examples. He first introduced the manuscript IOL Tib J 754, which was studied by Sam van Schaik and him about ten years ago. Because the manuscript was cataloged as a Tibetan manuscript, Chinese studies scholars rarely examined it. The manuscript is a scroll that consisted of three pieces. The recto of the manuscript is Chinese, but the verso is written in Tibetan with some Chinese scribbles. After their reconstruction, they found that some Chinese scribbles were used to record the Tibetan names and times in transcriptions. Galambos suggested that the manuscript was used by a monk traveler, who likely did not speak Tibetan, as a quasi-passport that allowed him to travel between the regions and language barriers. By the end of the lecture, Galambos reemphasized his four methodological suggestions.

Left: Manuscript IOL Tib J 754 schematic. Right: excerpt from Manuscript IOL Tib J 754 showing Tibetan and Chinese scripts. Slides courtesy of Imre Galambos. Republished with permission.

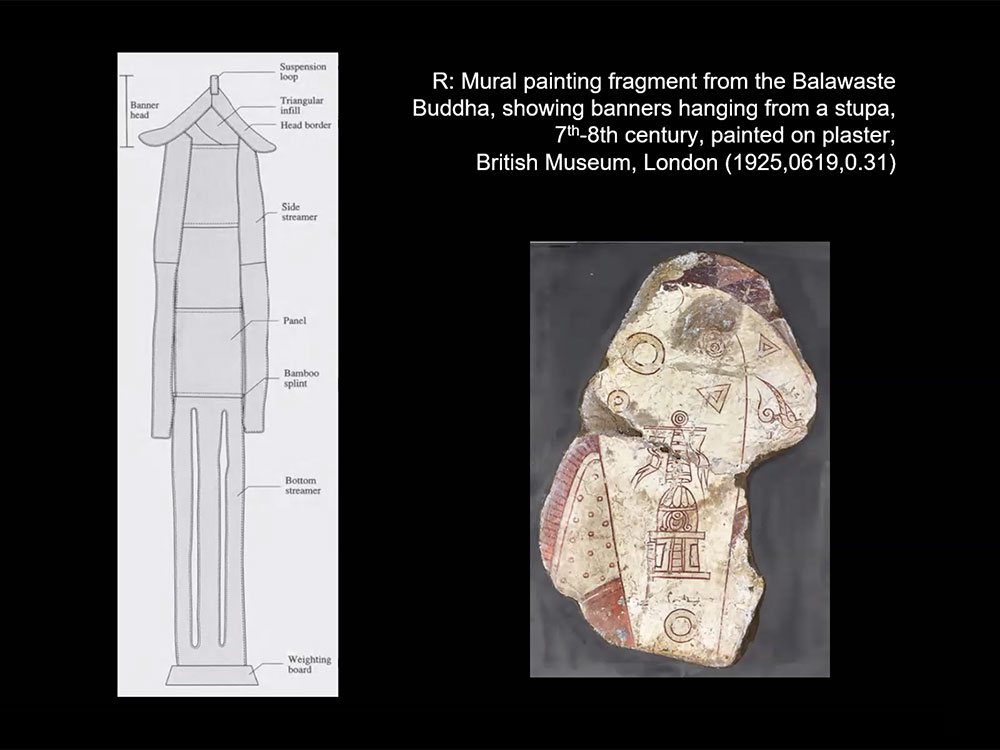

Wang began her lecture with some reasons behind her examinations of banner paintings. First, in contrast to mural paintings that are large and fixed to walls, banners are much smaller and portable. It makes them comparable to manuscripts in terms of their production process and functionality. Second, scholars have paid some particular attention to the material aspects of Dunhuang banners, such as their textile and stitching. Therefore, a dialogue could happen between the studies of manuscripts and banners in terms of their physical features. After a brief explanation of the multi-part structure of Buddhist banners, Wang emphasized their functionality. Some visual depictions of the banners suggest their ritual usage and their flexible structure enabled them to be twisted and to sway in the wind. In this sense, similar to manuscripts which often times are sutra copies prayers dedicated to the dead, banners were used for rituals for the dead and other religious purposes. Besides the banner painting, there are also colophons on banners that can be studied textually. Similar to paper manuscripts discovered in Dunhuang which had been recycled and reused, banners also have patches and repairs which signify their pragmatic usage. In short, similar to the manuscript studies, the study of Dunhuang Buddhist banners is not merely an art historian’s endeavor to examine iconographies but also textual and material evidence of the Dunhuang culture.

Left: banner structure schematic. Right: illustration of banners hanging from a stupa painted on a plaster fragment. Slide courtesy of Michelle C. Wang. Republished with permission.

Left: banner structure schematic. Right: illustration of banners hanging from a stupa painted on a plaster fragment. Slide courtesy of Michelle C. Wang. Republished with permission.

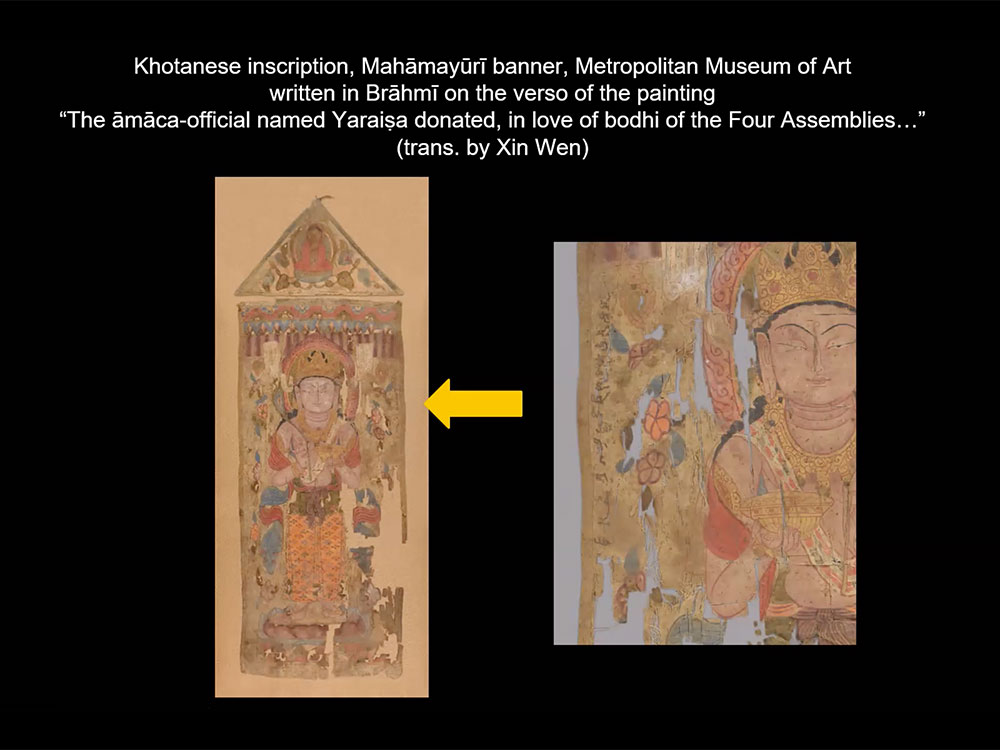

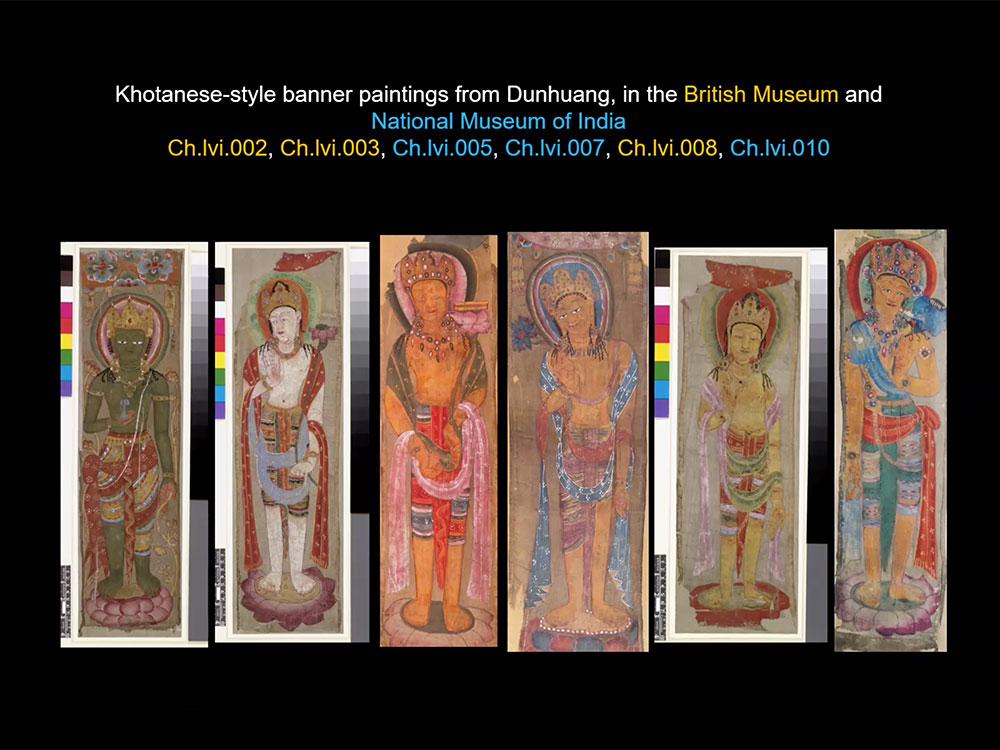

Wang moved on to give more insights on her recent collaborative research on the Banner with Mahāmāyūrī held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. First, she noted the varied disciplinary approaches to Buddhist art. Often, a textual historian would use iconography or other types of images as supplementary and secondary sources to assist their textual research based on the primary textual source. Wang tried to approach banner paintings without these disciplinary assumptions and presumptions. The Mahāmāyūrī banner is unique for many reasons. First, as a double-sided banner, some inscriptions are found on its verso that denotes the banner as a donation made by a Khotanese official. This leads to the potential of examining the object as a Khotanese painting, which is instead primarily known from mural paintings and paintings made on wooden panels. Second, there is a question about why the inscription was made on the verso instead of the recto of the banner, as in the manner of Chinese inscriptions. Wang suggested that the painting technique for this banner was derived from and influenced by the Tibetan painting technique of inscribing a thangka on the verso. There are many hybrid portable paintings in different formats that contain inscriptions written in multiple languages, such as Chinese and Khotanese. Seeing from this perspective, Wang started to find some common visual traits of the Khotanese style banner paintings divided between the British Museum and the National Museum of India. Some attention was drawn towards the textile of the Metropolitan Museum banner and the Silk Road textiles in general, from which we can find some common textile patterns. In addition, some comparisons were made between mural and banner paintings in terms of their styles. In the end, Wang suggested that there is an emergence of Mahāmāyūrī paintings in ninth-century Dunhuang that is related to the cross-cultural communication between the Khotanese kings and the Guiyijun rulers with their intermarriage and other political acts.

Khotanese inscription on Mahāmāyūrī banner. Slide courtesy of Michelle C. Wang. Republished with permission.

Khotanese-style banner paintings from Dunhuang. Slide courtesy of Michelle C. Wang. Republished with permission.

The workshop then moved on to the Q&A session. There were first few general questions about the theme of the workshop and methodology. A student asked why the workshop is centered around ninth- and tenth-century Dunhuang and highlights its multi-cultural context. Galambos responded that the Guiyijun period is unique for two primary reasons. First, the Dunhuang library was sealed shortly after the production of these materials in the early eleventh century. Therefore, by chance, there are relatively abundant datable materials that come from the tenth century. Second, because of the geopolitical context of this period, the Buddhist communities of the region incorporated people from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Further, Galambos insisted that the Guiyijun could be seen as an independent state where cross-cultural communications happened, and people should not presume the Dunhuang area was inherently a part of the Chinese territory. Then, a question was asked about whether the banners preserved in museum collections can reflect their actual usage. Wang replied that, although many objects were designed and produced for specific purposes, without knowing the exact context of the production of the specific banner, there are always possibilities that the banner was used for other purposes.

Then, some specific questions were raised about the objects examined in the workshop. First, the back cover of the manuscript IOL Tib J 754 includes the founding record of the Gantong Monastery 感通寺 that is deemed as being transcribed from a stele. The question was how often we may find Dunhuang manuscripts that contain transcriptions from steles or other formats of records. Galambos explained that, actually, the Gantong Monastery is a special case since it was founded on the basis of a miracle, and therefore people may carry some copies of its rubbings while traveling across the region. In general, the manuscript does not produce the original text, and the format of a text is fluid. The text was often transcribed and copied in different formats. Regarding the making of the banner paintings, one student asked whether the Tibetan thangka influenced the Khotanese painting techniques or vice versa. Wang answered that it is more likely that the Khotanese painting was influenced by the Tibetan thangka. Lastly, some discussions happened about orthography, especially concerning how to determine whether different texts were written by the same hand or not. Galambos suggested that we should not only look at one’s handwriting but also pay attention to the style. Wang supplemented that there are scholarships on Chinese calligraphy that have thoroughly analysed people’s handwriting and calligraphy style. However, in terms of determining the painting’s style, it is hard to conclude whether the materials were made by the same hand or not since many painters may come from the same workshop or were trained in the same place. Thus, art historians tend to reconstruct sets of criteria for the regional style instead of attributing Dunhuang artifacts to specific persons. Finally, Galambos acknowledged that it could be a good approach to future studies of Dunhuang manuscripts by further investigating whether certain manuscripts were written by the same person.

In the third session, the students were divided into six groups with different assigned materials. Groups 1 (P.2374), 3 (P.3748), and 5 (P.3826) were assigned with three Dunhuang manuscripts from the Pelliot Collection, and groups 2 (British Museum; 1919,0101,0.142), 4 (Victoria and Albert Museum; STEIN.621), and 6 (British Museum; 1919,0101,0,216) got three images of banners collected by Stein. Students were encouraged to think about the methodologies and approaches to these materials. For example, what are some good scholarly questions that can orient our studies? How should we study and what is the limitation of our approaches? After roughly eight minutes of breakout room discussion and examination of the material, students came back with different questions and speculations.

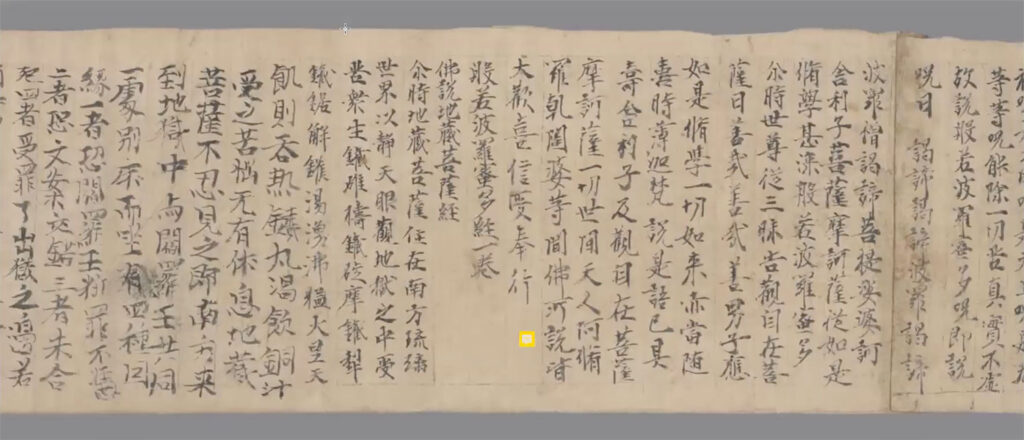

For the groups assigned manuscripts, students identified several common features and techniques regarding the making of the manuscripts. First, a manuscript usually consists of multiple sutra copies, and a colophon is given by the end. The manuscript papers are often stitched or glued together for making an extension. Sometimes, by comparing the size of the manuscript and looking at the evenness of the edges, we may reconstruct the production of the paper. For example, the P.3748 manuscript has an even bottom edge but an uneven upper edge. Considering its width is half of the normal ones, we may postulate that the paper was halved from a full-size manuscript paper. Second, in terms of functionality, the manuscripts are usually produced for votive purposes, such as commemorating the dead and seeking relief from illness or misfortune. Clearly, the motifs of some of the copied sutras are prolonging one’s lifespan and the colophons of many manuscripts state their purpose as transferring merits to the deceased. Third, there could be multiple changes of hands. It is possible that considering the making of the manuscript as a dedication to the dead, the production of some manuscripts can be a family project that every family member contributes a little bit of prayer or merit for the deceased.

A section of Dunhuang manuscript P.3748. Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits. Pelliot chinois 3748.

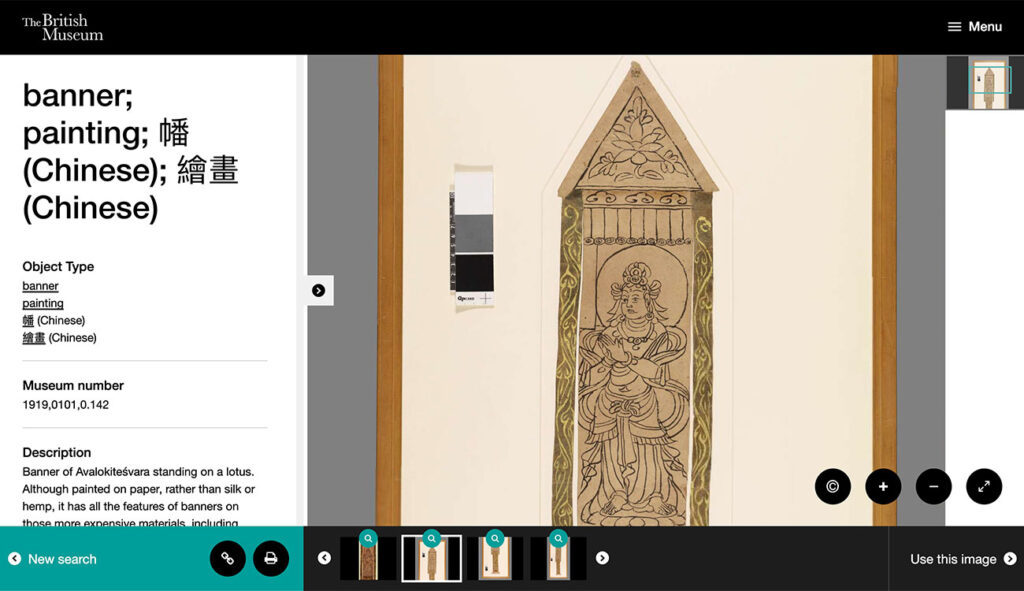

For the groups assigned banners, students focused on the production and function of the banners. First, some evidence suggests some banners were mass-produced for consumption. Group 2 noticed that their banner is made of paper, instead of more precious textiles like silk. This bodhisattva painting has a relatively simple composition and some potential flaws, such as being asymmetrical. Overall, the banner is seemingly unfinished. Wang first praised their observations and replied that the banner was not a preparatory sketch but rather, a finished product that has the supposed votive function. It was likely produced by a workshop that was mass-producing similar banners for potential buyers. Second, the examination of the inscription of the banner can explain its practicality and its supposed usage. Some banners made with delicate materials, such as the no.216 collected in the British Museum, were donated by a high-ranking state official for his parents.

A bodhisattva banner painting on paper. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In sum, the workshop successfully put manuscript studies and art history in a productive dialogue. As the workshop emphasized, we should approach Dunhuang studies from a multi-cultural perspective and try our best to avoid disciplinary biases. Scholars should consider medieval Dunhuang as a place where different ethnic and cultural groups converged. Regarding the research methodologies, Galambos and Wang both stressed the importance of examining the physical and material aspects of Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings. We should study inscriptions, iconographies, and materiality complementarily, instead of studying one for the other. Further, scholars should think more critically about the functionality of Dunhuang materials beyond their commonly assigned religious significance.

Guanxiong Qi is currently a third-year M.A. student in the Department of Religion at Florida State University. He studies late-imperial Chinese Buddhist culture, such as Buddhist patronage network, marriage, and cuisine. He is also interested in Yogacara Buddhism.

Click here to the original posting