May 26, 27, 31, June 2, 2022

Written by Tianjie Yin, École Pratique des Hautes Études

In order to explore the subject Continuous Revelations”, cluster 2.3 of FROGBEAR hosted an online workshop at the end of May and the beginning of June. Seven sessions were presented by Philip Clart, Rostislav Berezkin, Katherine Alexander, Zhenzhen Lu, Nan Ouyang, and Gregory Scott on diverse aspects of baojuan寶卷 (precious scrolls).

Session 1-1

On May 26, 2022, Professor Philip Clart (Leipzig University) started the workshop with a clear introduction in which he focused on three topics: the types of baojuan, the historical development of baojuan, and studies of baojuan.

On the first topic, he explained that baojuan can be generally divided into two types: sectarian baojuan and narrative baojuan (which this workshop focused on). He demonstrated the typology of narrative baojuan by illustrating how to identify the different types of narrative baojuan and how to distinguish baojuan from other prosimetric literature such asdaoqing 道情.

Secondly, Professor Clart outlined baojuan’s historical development according to chronological order: the bianwen 變文of the Tang dynasty and Five Dynasties were evidentially linked to the baojuan of Yuan and Ming dynasties through the Song-period texts. In the Ming dynasty, few narrative baojuan survived, and in the Qing dynasty, a large number of narrative baojuan appeared. Up to the nineteenth century, baojuan evolved with the development of printing techniques, thus we can see its commercialization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Thirdly, Professor Clart discussed the history of baojuan studies. He pointed out that there were three research foci: scholars paid early attention to the sectarian baojuan; after the 1980s in the PRC, some Chinese scholars collected the texts and catalogued them; a third research focus was narrative baojuan.

Session 1-2

Professor Rostislav Berezkin (Fudan University) presented a lecture titled ‘Ritualized Recitation Baojuan of Incense Mountain in the Changsha area and popular Buddhist beliefs in China’ that showcased his fieldwork.

Professor Berezkin introduced the concept of baojuan, highlighting that they are living tradition in Changshu, China, and introduced the tradition of Changshu baojuan.

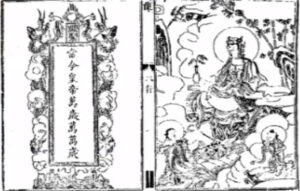

He showed the major works of Chinese narrative literature which feature the Miaoshan 妙善 story (connected to Guanyin story) and the versions of Xiangshan baojuan 香山寶卷 (The Precious Scroll of Incense Mountain), especially the earliest known version, Dabeipusa Xiangshan baojuan 大悲菩薩香山寶卷 (Scroll of Incense Mountain of the Bodhisattva Guanshiyin of Great Compassion), which was reprinted in 1772.

Frontispiece illustrations from the edition of Xiangshan baojuan (made in 1773 in Hangzhou, Zhaoqing jingfang昭慶(慧空)經房). Source: Yoshioka Yoshitoyo chosakushū 吉岡義豊著作集 (Collection of works by Yoshioka Yoshitoyo). Tokyo: Gogatsu Shobō, 1988 –1990, vol. 4, p. 245. Republished with permission.

While sharing results from his fieldwork, Professor Berezkin introduced some general situations that he noted in Xiangshan such as the model of the offering altars, the vegetarian and meat altars, and the ritual process. He pointed out the relationship between the beliefs of Xiangshan and the local ones, which are Buddhism, Daoism, and other local beliefs. Then he demonstrated some additional elements such as printed texts, performers of texts, and small scrolls.

Female worshippers participating in a ritual in Xiangshan. Photos provided by Rostislav Berezkin. Republished with permission.

He then mentioned that the “Asking for the elixir” ritual is the most spectacular part of the performance and explained that the rituals are accompanied by recitation. After this, he showed some photos of the female audience’s participation.

To support his point of view, he shared some historical resources such as the description of Pingyao zhuan 平妖傳: the old legend, the historical evidence, as well as the relatively modern scriptures in order to clarify the relationship between the audience’s identification and the ritual characteristics.

Session 2-1

On May 27, 2022, Professor Katherine Alexander (University of Colorado, Boulder) explained that the subject of her talk is on the three main types of baojuan and introduced her own research.

In the first part, she began by introducing the places where we have access to the relevant texts and three types of printed formats, such as the sūtra style (text style), the woodblock print codex, and the lithographed codex. She then showed an example of each style using Tanshi wuwei juan 嘆世無為巻(Scroll of Lamenting the World and Non-Action), Liu Xiang baojuan劉香寶卷 (The Precious Scroll of Liu Xiang), and Zhenzhu ta baojuan珍珠塔寶卷 (The Precious Scroll of the Pearl Pagoda). For each of these examples, after sharing images and pointing out special features, she explained how the text is catalogued in Zhongguo baojuan Zongmu 中國寶卷總目 (Catalogue of Chinese precious scrolls), a key reference work by Che Xilun.

In the second part, she guided the audiences to participate in break-out rooms with pre-prepared texts to help every participant look for some specific features, to explore the text’s religious significance, and to discuss any questions encountered while skimming the chosen text. The audiences were divided into two-person groups and discussed for ten minutes. After that, Professor Alexander encouraged the audience to share some of the questions that came up during the discussion. During the question and answer period, the discussion concentrated on topics such as an interesting edition of Tangseng baojuan 唐僧寶卷 (Precious scroll of Monk Tang) held at Harvard Library, the ways to categorize baojuan, the relationship between the images as well as their effects on the texts, and also on the references of Zhenzhuta baojuan 珍珠塔寶卷 (Precious scroll of the Pearl Pagoda).

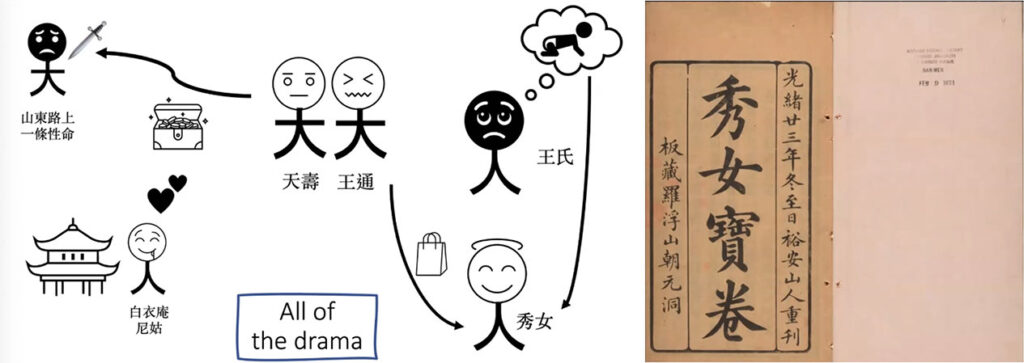

In the last part, Professor Alexander presented her recent research on Xiunü baojuan 秀女寶卷 (Precious Scroll of Xiunü) by analyzing its textual structure and illustrating the religious and the narrative structure of the drama. Separating the main body narrative from the opening and the closing sections that focus on lyrical lessons about charity and karmic causation, she also explored the way the drama happened, explained how she is looking into the social and religious contexts that produced Xiunü baojuan 秀女寶卷and the influences it received from other baojuan.

Left: llustrations shared during the presentation by Katherine Alexander. Right: Title page of Xiunü baojuan 秀女寶卷 from Harvard-Yenching Library collection. Republished with permission.

Session 2-2

Professor Zhenzhen Lu (Bates College) focused her presentation on baojuan and Chinese “popular literature.”

Firstly, she commenced with a discussion of how early 20th century scholars such as Zheng Zhenduo placed baojuanwithin the genealogy of su wenxue 俗文學 (“popular literature”). She drew links between baojuan and other genres of Chinese vernacular literature by citing their shared language and prosimetric form, musical content, as well as repertoires of stories. Then she pointed out that how the collection of baojuan took place alongside that of a much larger body of secular literature in the early 20th century.

Secondly, she expressed some thoughts on possibilities for studying baojuan. She started with introducing perspectives from the social history of books in late imperial China, as well as approaches from manuscript studies. Then she outlined different kinds of physical information to pay attention to when studying baojuan, and also comparative possibilities between baojuan and other types of books.

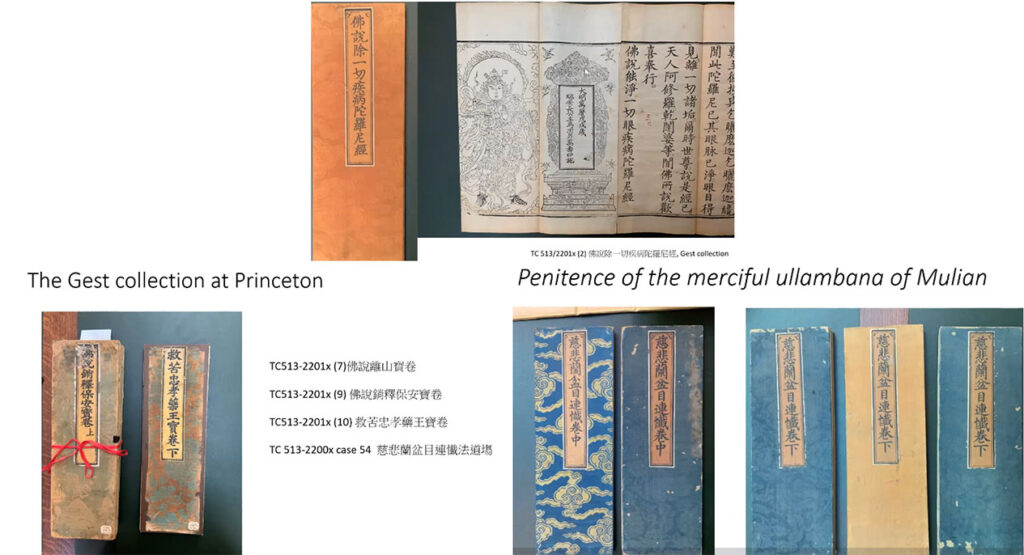

In the third part, Professor Lu turned to a case study of items from the Ming court. She presented early extant baojuan and a penitence book from the Gest collection at Princeton University Library, the Penitence of the Merciful Ullambana of Mulian dated to the Wanli era.

Images courtesy of the East Asian Library, Princeton University Library. Slides by Zhenzhen Lu. Republished with permission.

She traced proofs of sponsorship of the printing of several early baojuan by female members of the court, and discussed in detail the example of Princess Rui’an, sister of the Wanli emperor. She deduced the multi-faceted religious activities of the Ming court, and how palace women and eunuchs sponsored the printing of both canonical and non-canonical texts. She ended this part by pointing out the likely involvement of Tibetan monks in consecrating books such as the Penitence and the Yongle Northern Canon永樂北藏 (which was expanded in the Wanli era).

In her conclusion, she invited the audiences to rethink the agents of “popular literature,” examine the varied contexts of religious printing, and to pay attention to physical aspects of baojuan beyond the texts themselves.

Session 3-1

On May 31, 2022, Dr. Nan Ouyang (Ghent University) presented a talk entitled, ‘Dizang Baojuan and the Jiuhua pilgrimage’. She divided her talk into four parts.

In the first part, she introduced her research goals: the first one is focused on reasons why baojuan are important for the development of religious traditions on the ground; the second is an examination of the texts and their performances, centering on Mount Jiuhua and its rising fame in the Ming-Qing periods.

In the second part, Dr. Ouyang remarked on the evolution of the local legends of Jin Dizang 金地藏 on Mount Jiuhua 九華山 in several baojuan texts, many of which are catalogued by CRTA (Chinese Religious Text Authority).

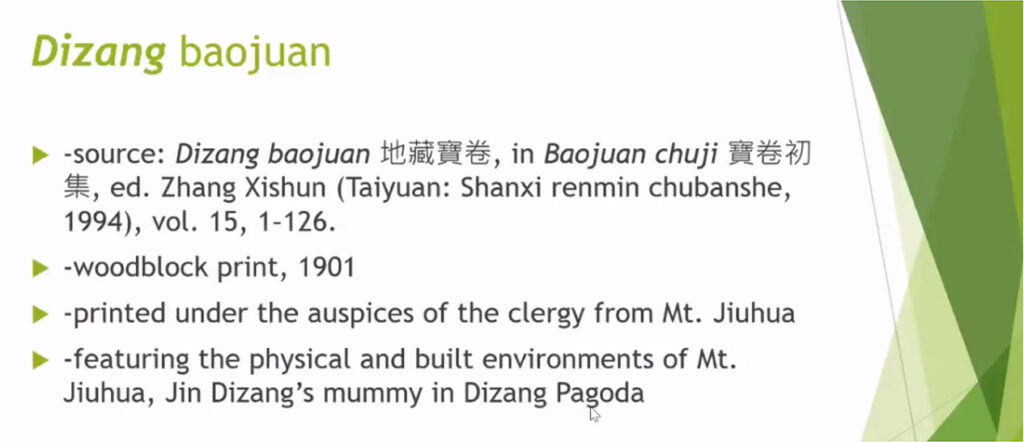

In the third part, in order to explain the adaptation of the local legends in baojuan, Dr. Ouyang showed methods to read baojuan. She cited some examples of Dizang-themed baojuan and read one example, the edition included in the facsimile reprint collection Baojuan Chuji 寶卷初集 (The first collection of baojuan), for some detailed demonstrations of the iconographies, the text proper, and publication information. At the end of this part, Dr. Ouyang presented more features of this Dizang Baojuan 地藏寶卷 (Precious Scroll of Kṣitigarbha) such as the origin, funding for printing, as well as its emphasis on the environment of Mount Jiuhua.

Description of Dizang baojuan. Slide by Nan Ouyang. Republished with permission.

In the fourth part, she concluded by demonstrating how to use the platform Chinese Religious Text Authority to search for baojuan in research, since the platform includes the Dizang Baojuan mentioned above.

Session 3-2

Dr. Gregory Adam Scott (University of Manchester) demonstrated an introduction of the Chinese Religious Text Authority (CRTA) database.

Of the four topics prepared by Dr. Scott, the first part was focused on the project’s aims and ethos, which are to resolve research difficulties according to the characteristics of Chinese Studies, to generate an authoritative, accessible, editable, and interoperable base, and to conserve a map to the “territory” of Chinese religious texts.

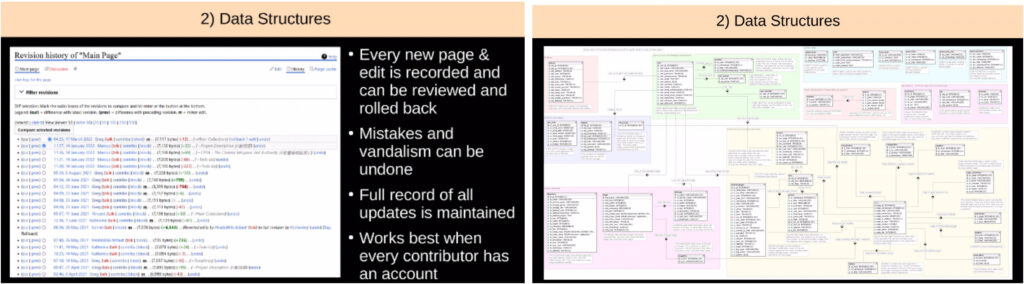

For the second topic, Dr. Scott introduced the data structures of this resource which have some similarities to Wikipedia that allow more organized information to be presented to users in a quicker and clearer way. Registered users can record, review, and edit every page, correct mistakes and vandalism, and maintain updated records with their own account; while the visiting users can browse and view the information.

The data structure. Slides by Dr. Gregory Scott. Republished with permission.

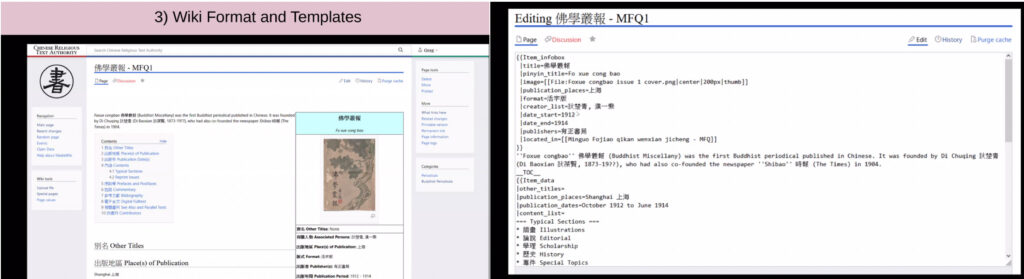

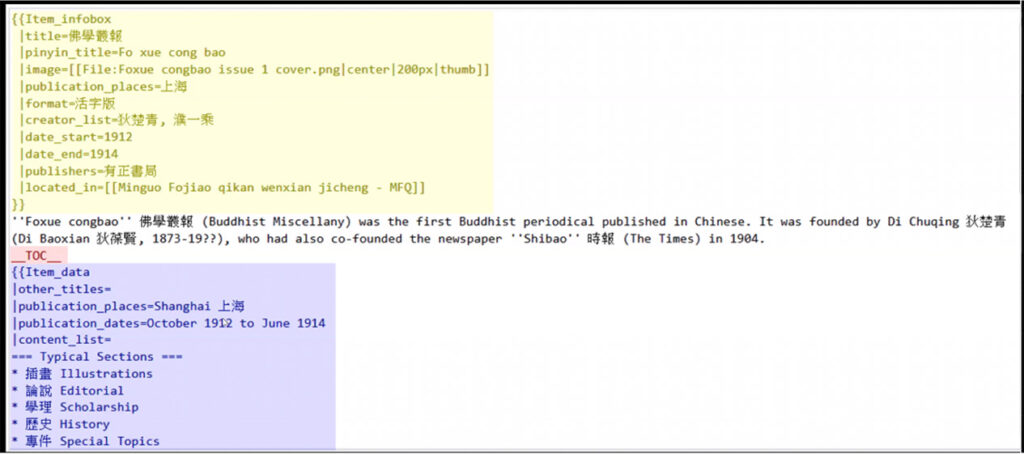

Thirdly, Dr. Scott led the audience to understand the CRTA’s format by comparing it with Wikipedia and introduced the templates it uses to organize data and to ensure that the key data of each item is fed into the underlying database.

The format and templates of CRTA. Slides by Dr. Gregory Scott. Republished with permission.

In the last part, Dr. Scott gave some instructions for entry creation in the CRTA to teach potential users some basic methods of creating information. He encouraged the audience to try something on CRTA such as creating or editing one page before the next workshop session, which would teach more technical details.

The operational procedures of the CRTA. Slide by Dr. Gregory Scott. Republished with permission.

Session 4-1

On June 2, 2022, Dr. Scott guided the audiences how to work on CRTA. He started this session by a general discussion and then focused on how to distinguish and search for a simplified Chinese character title versus a traditional Chinese character title.

Then Dr. Scott launched discussions with the workshop participants who had already worked on the website to share their experiences of editing the information online, such as how detailed the information should be and how to link different pieces of information together.

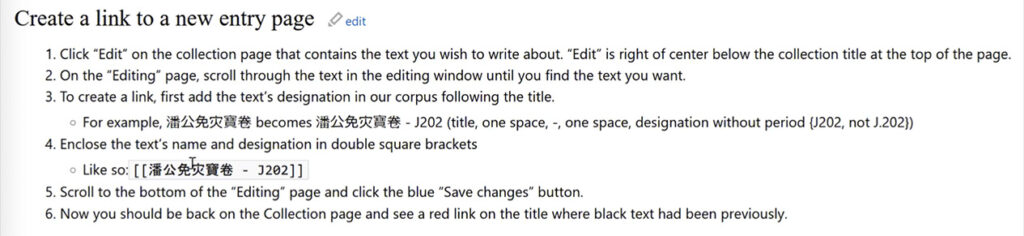

Dr. Scott then introduced the guide to entry creation in CRTA by showing the creation of a link and how to edit the information.

Description of how to link a new entry page. Slide by Dr. Gregory Scott. Republished with permission.

Additionally, Dr. Scott explained how to delete or move pages, and also led a discussion about the user page which is for presenting private information which does not need to appear on the main CRTA wiki pages.

After more interactions with the audience, Dr. Scott divided them into different break-out rooms to discuss the methods of editing pages on CRTA. After that, Professor Alexander concluded that we should only describe texts that we are familiar with and have carefully examined, and create separate entries for different versions of a same title New entries are always preferred even for newly-added versions of documents that already existed on CRTA. Dr. Scott also emphasized that the CRTA is a community where an editor’s work will be seen by others, so awareness and carefulness are appreciated while working on this database.

This cluster concluded with plenty of valuable discussions that tried to clarify the history, the fieldwork, and the various collections of baojuan as well as the technologies designed to catalog and study not only baojuan but also other materials related to Chinese religion. As a reporter, I was inspired by the informative talks shared by the scholars from the different perspectives of views.

Author Bio:

YIN Tianjie, PhD candidate in L’École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris, France, under the direction of Professor Vincent Goossaert. His doctoral research focuses on the Daoism, especially on the Daoist liturgical Shuilu paintings in Qing period of Sichuan region.

Click here for the original posting