By Junfu Wong, University of Cambridge

The Frogbear Cluster 3.1 entitled “Multicultural Dunhuang: Manuscripts and Paintings” was a fieldwork summer programme co-organised and taught by Professor Imre Galambos, a Dunhuang manuscript scholar and codicologist at the University of Cambridge, and Professor Michelle Wang, an art historian of the Silk Road and Buddhist Art at Georgetown University, with an aim of examining the connections between Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings during the tenth century. The programme consisted of field visits to the British Museum and the British Library, and lectures given by guest speakers. It was directed at a group of ten student participants selected from various institutions in North America and Europe, including Harvard University, Princeton University, University of Virginia, University of British Columbia, Leiden University, Ghent University, and Hamburg University. The programme took place in London from August 1 to 5, 2022, and consisted of four parts: a two-day workshop at the British Library (August 1–2), a two-day workshop at the British Museum (August 3–4), a closing guest lecture by Professor Susan Whitfield at SOAS, University of London (August 5), and a field visit to the Victoria and Albert Museum (August 5).

01 August

On August 1, all the participants gathered at the hotel lobby for an orientation session to introduce themselves to the group and receive face masks and rapid covid test kits. Shortly after that, they attended their first session on manuscripts at the British Library, examining a wide range of Tibetan and Chinese manuscripts from Dunhuang. Comparing these two groups of manuscripts was a useful exercise for students to learn to read the manuscripts from a codicological aspect andobserve unnoticed contacts of different cultures along the Silk Road.

The morning session featured a lecture by Ms. Mélodie Doumy, the Curator of Chinese Collections at the British Library, and Dr. Sam van Schaik, Head of the Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library, on the Tantric ritual implements in the Stein Collection at the British Library. Students were particularly fascinated by the display of a manuscript in a rare fan-like shape which, according to Ms. Doumy, could be an object used in ritual performance since she has discovered a similar object held by bodhisattvas in Dunhuang paintings. Dr. Sam van Schaik introduced Tibetan manuscripts and explained the basic characteristics of their book form, production, and usage. By examining them closely, students realised that the layout and format of later Chinese codices in the ninth and tenth centuries could be a result of an influence from their Tibetan counterparts.

After a short lunch session joined by Ms. Mélodie Doumy and Dr. Sam van Schaik, the afternoon session, led by Professor Imre Galambos, addressed the importance of paying attention to the physical features of manuscripts. By going through a range of Chinese manuscripts in different physical forms, he outlined the history of the development of book forms in Dunhuang to set the scene. He then zoomed in on their layout and colour and explained how these finer details could provide additional information about the manuscript and shed light on the group behind the manuscripts. For example, with the case study of student-copied manuscripts S.395 and S.728, Professor Galambos provided his insight on this group of manuscripts and suggested that the lay students might copy them as part of their writing practice or coursework. In addition, Professor Galambos touched upon the concept of the continuous use of manuscripts to highlight the significance of the function of manuscripts and the ways they were used or reused.

2 August

The second day of the programme was devoted to Chinese manuscripts. In the morning and afternoon sessions, Professor Imre Galambos introduced another set of manuscripts and explained in detail the layout and format of different book forms and the use of punctuation and correction marks in premodern manuscript culture. He also discussed the custom of manuscript recycling in Dunhuang and the different contexts where this might happen. Among the requested items was one manuscript of Saddharmapundarikasutra, S.5319, sponsored by the Tang court, which demonstrated the highest quality of sutra copying during the seventh century. Apart from using this fine copy to contrast with ordinary manuscripts, Professor Galambos also urged the students to pay attention to the colophons as they would usually provide key information on the process of sutra copying and the geographical and religious contexts in which it was done.

The second day also included a visit to the Conservation Department at the British Library. During this short but inspiring session, the conservators explained their usual procedures for treating and preserving old manuscripts. Under their supervision, students learned how to identify the damaged parts on a manuscript, what could have caused the damage, and how to deal with the damage. They also had the privilege of seeing some manuscripts in their original state before any intervention on the part of the conservation team. The clear distinction between these manuscripts and those that had undergone conservation alerted students to the potential bias that emerged when viewing manuscripts. It also made students realise that although the practice of conserving was necessary for preserving the old manuscripts, it would unavoidably alter the visual appearance and physical condition of these manuscripts and in some cases remove crucial clues concerning their use. Thus, conservation practices should always be carried out with minimum interventions. The group was also surprised by the appearance of traces of excrement, probably from bats, on the manuscripts. Such a discovery lent additional evidence to the claim that the Library Cave where the manuscripts were discovered was in use for an extended period before it was sealed and was possibly used to store the documents.

3 August

Professor Michelle Wang started the two-day session at the British Museum with an introduction to the Khotanese and Tibetan materials in Dunhuang, including three album leaves painted with spirits with animal or bird heads and written with both Chinese and Khotanese inscriptions. Professor Wang highlighted the multicultural and multilingual nature of the Dunhuang community and explained the sequence in which the inscriptions of both languages were written. Professor Wang also introduced to the group two sutra wrappers made in different forms and from bamboo splints, paper, hemp, and silk textiles. The characters written on the wrappers, yin (陰) and kai (開), respectively, triggered heated discussions over their possible meanings. While the term yin (陰) might hint at the familial clan which sponsored the manuscript, or served as part of an archival series number similar to the Buddhist qianziwen (千字文) system for labelling or grouping the manuscripts, the term kai (開) could be taken at face value as an indicator of where the sutra should be unfolded from. As a conclusion, Professor Wang introduced several paintings about Avalokiteśvara as a set and showed how the images and posture of the deities could be read as visual clues in examining the function of these paintings. Through this, Professor Wang successfully demonstrated an inspiring way to read images and texts as an organic whole.

Dr. Lilla Russell-Smith, Curator of Central Asian Art at the Staatliche Museen of Berlin, further complicated the picture by introducing certain Uighur materials. Dr. Lilla Russell-Smith presented her research on Uighur patrons and Pure Land motifs in Dunhuang paintings. She shared her thoughts on a fragmented yet fascinating piece of Pure Land painting shown in an architectural setting.

The day was concluded with a lab visit guided by Dr. Diego Tamburini, Polymeric and Modern Organic Materials Scientist at the British Museum, who patiently explained the procedures and chemical experiments that a painting might have gone through to acquire a detailed scientific analytical report.

4 August

The final day at the British Museum started with Dr. Yu-ping Luk, the Basil Gray Curator at the British Museum, who lectured on the donor figures and their inscriptions on Dunhuang paintings. Dr. Luk brought in a wide range of paintings with donor images and explored the identity of these donors and their wishes. She remarked that the donors who appeared on Dunhuang paintings were not necessarily only those who were alive, since the donor images would sometimes also include deceased family members. Such a practice resonated with the common motif of praying for deceased ancestors deeply rooted in Chinese society in the premodern period. Dr. Luk also urged students to pay extra attention to the direction of writing that went from left to right, a phenomenon closely linked with the transregional nature of the patronage group.

Joint side by side with the talk was a session with Dr. Diego Tamburini, who showed how scientific analysis of the textile dyes on silk could extend our knowledge of the users of the artefacts. He explained that most of the colour we saw on monochromic clothes was the result of mixing at least three shades of the same colour. Students were amazed by the fact that some of the natural dyes, namely turmeric and amur cork tree, would glow when UV torch light was applied. Even though this did not suggest anything in regard to how the mural paintings were supposed to be seen inside the cave, the experiment still lent a new lens to the study of donors in Dunhuang and their culture, as the use of dyes, whether illuminated or not, were the result of careful selection. Such a careful selection of pigments or materials could be valuable clues reflecting hidden religious connotations unnoticed if approached from purely a doctrinal perspective. This perfect combination of visual and scientific analysis of paintings revealed that a stronger collaboration between chemistry scientists, art historians, and codicologists could potentially benefit the field of Silk Road Studies.

The day was concluded with a visit to the Hirayama Studio at the British Museum, where East Asian paintings and scrolls were conserved. Students enjoyed an orientation session in this lovely studio decorated with wooden furniture and tatami mats.

5 August

The final day of the workshop began with a lecture by Professor Susan Whitfield who introduced her current project Nara to Norwich and the current trend of applying digital humanities in the research of manuscripts and the field of Silk Road Studies.

After the lecture, the group took a short lunch break at Russell Square where they could have a more informal interaction with Professor Susan Whitfield and learn about the history of the International Dunhuang Project. The group then visited the Victoria and Albert Museum and was greeted by Ms. Ricarda Brosch, Assistant Curator of the East Asian Section at the museum. While at the Victoria and Albert Museum, students were encouraged to explore the museum on their own and had the chance to examine artefacts and statues from a close range.

The fieldwork programme ended with a general discussion at the dinner table, where students expressed their gratitude for being included in the workshop and actively shared their thoughts about the programme and what they gained during this intensive five-day training. The interdisciplinary nature of the programme invited students from different backgrounds to examine the connection between Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings and to develop new theories or methodologies applicable to both. The interdisciplinary dialogues generated in the course of the programme also fostered collaborations among young scholars and sparked new ideas that would turn into new projects in the future.

Conclusion

In sum, the programme successfully put manuscript studies and art history in a productive dialogue. The interdisciplinary nature of the programme also allowed images and texts to synergize with each other and fostered new research methodologies applicable to the study of manuscripts and paintings. Students had an invaluable experience handling manuscripts, examining portable paintings and manuscripts of all forms at close range, and learned how combining the knowledge of art history and codicological studies could benefit their research on manuscripts or portable paintings. Most students had no hands-on contact with these primary sources before the programme due to the pandemic or early research stages, which again bookmarked the importance of the programme. The conversations over the lunch and dinner table also added to the programme another layer of academic interaction, providing students with a friendly and safe environment to freely express their thoughts, share their enthusiasm for learning, and network with other promising young scholars.

Reflections from Student Participants

The FROGBEAR Multicultural Dunhuang workshop provided the ideal setting for me to begin my Ph.D. right after it. After two years of remote learning, it was great to finally meet peers in person and gain experience of viewing primary sources of Dunhuang manuscripts and paintings in the Stein collections. It was quite surprising how much bigger the actual size of the silk paintings was than what was shown on the monitor. Through a five-day workshop, I gained insights into a selection of Dunhuang scriptures, paintings, and textiles from diverse perspectives across disciplines. The discussions about the interconnection between studying manuscripts and art objects for Dunhuang material cultures in the 10th century inspired me to think critically about my future studies in this field.

- Catherine Luk (University of Virginia)

This workshop gave me the opportunity to go to the British Library, British Museum, and Victoria and Albert Museum, which I should have done a long time ago. It was also an excellent opportunity to meet and get to know distinguished researchers in different fields (Michelle C. Wang, Imre Galambos, Susan Whitfield, Sam van Schaik, Mélodie Doumy, Lilla Russell-Smith, Yu-ping Luk, and Diego Tamburini) and a very good team of young scholars. Readings, although overwhelming in some cases given the date that they were shared, were certainly an excellent way to prepare the sessions and ensure the interactive nature of the workshop.

- Laurent Van Cutsem (Ghent University)

The very first-hand experience observing, reading and valuing the very Dunhuang fragments by myself is what I treasure most now. Thanks to the rich reading materials and the detailed instructions by Professor Wang and Professor Galambos, I have a better understanding of the Dunhuang manuscript culture in 9-11 centuries. Of course, the interdisciplinary method of studying the fragments, not only through the images but also the texts and in more other optional ways, broaden my horizons. Also, not only the textual or image information in the fragments but also the fragments themselves are crucial to understand the Dunhuang manuscript culture as a whole, thus it touched me a lot when we saw the skillful preservation of the Lotus Sutra manuscripts in BL as well as the advance dyestuff research in BM. At last, I could know and befriend other members in the workshop, which also helps me to get out of my limited sphere of study and to acquaint more with the other-world.

- Meng Xiaoqiang (Leiden University)

I found the workshop tremendously eye-opening and inspiring and I feel extremely grateful to have been able to see, touch and learn about Dunhuang manuscripts and portable paintings in a physically intimate way. From my point of view, I also think the workshop is very nicely designed. The first day at the British Library brought us back to a whole bundle of manuscripts and items in one Dunhuang cave. That was the first time for me to experience the Dunhuang materials not as mutually isolated islands but as an archipelago—we got to not only observe the nature of individual objects but also the affinity that had bonded the group, both physically and symbolically. Our trip to the conservation office at the British Library definitely highlighted the second day of the workshop. It was exciting and inspiring to see the damages and repairs of manuscripts and contemplate on the long and colorful afterlives of them, which used to be so carelessly forgotten—what a shame! The following two days at the British Museum were equally full of excitement and enlightenment. In the third day session we viewed some portable paintings bearing similar visual settings and iconography, which brought our attention to the perspectives, colors, brushes, styles—a fruitful journey through the field of close looking and formal analysis. On the next day, we got to examine the images of donors across a variety of different forms and settings, which nicely raised the follow-up questions about “the content of forms”, the temptation and risk of iconographical interpretation. Not to mention the mesmerising experience of UV torch and dye analysis—which allowed us to get a peep at the colorful world in the eyes of 10th century Dunhuang residents. The lecture by Susan Whitfield and the visit to V & A museum on our last day wrapped our fabulous trip with a perfect ending which is both reflective and provoking.

- Yalin Du (Princeton University)

It is fascinating to have a chance to smell, touch and feel the weight of the authentic manuscripts. As an essential part of rituals, we hardly have opportunities to do the same thing to manuscripts as people did in the past. The fieldwork in the British Library and the British Museum is a precious memory.

- Xinshu Chen (Hamburg University)

Text, images, and materiality are closely intertwined in the Dunhuang materials. Given such nature of the materials, the structure of this workshop encourages me to ask new questions about my visual data and to make better connection between art, its role in localised cult, and the multicultural community in Dunhuang. With the help of the workshop, I developed a more comprehensive picture of Buddhist communities in Dunhuang.

- Clara Ma (University of Virginia)

(All photographs included in this report are taken by Junfu Wong and granted with his permission for republishing.)

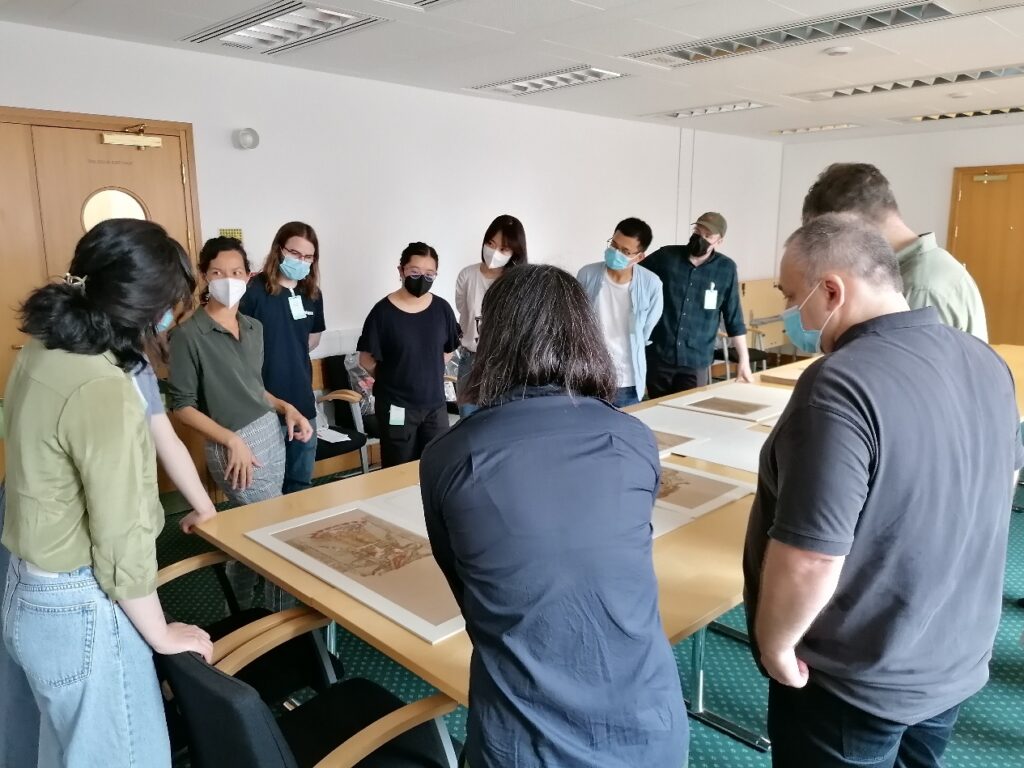

(Figure 01) Students listening to the introduction of the manuscripts on display by Ms. Mélodie Doumy. Republished with permission.

(Figure 01) Students listening to the introduction of the manuscripts on display by Ms. Mélodie Doumy. Republished with permission.

(Figure 02) A general introduction of Dunhuang Library Cave by Ms. Mélodie Doumy. Republished with permission.

(Figure 02) A general introduction of Dunhuang Library Cave by Ms. Mélodie Doumy. Republished with permission.

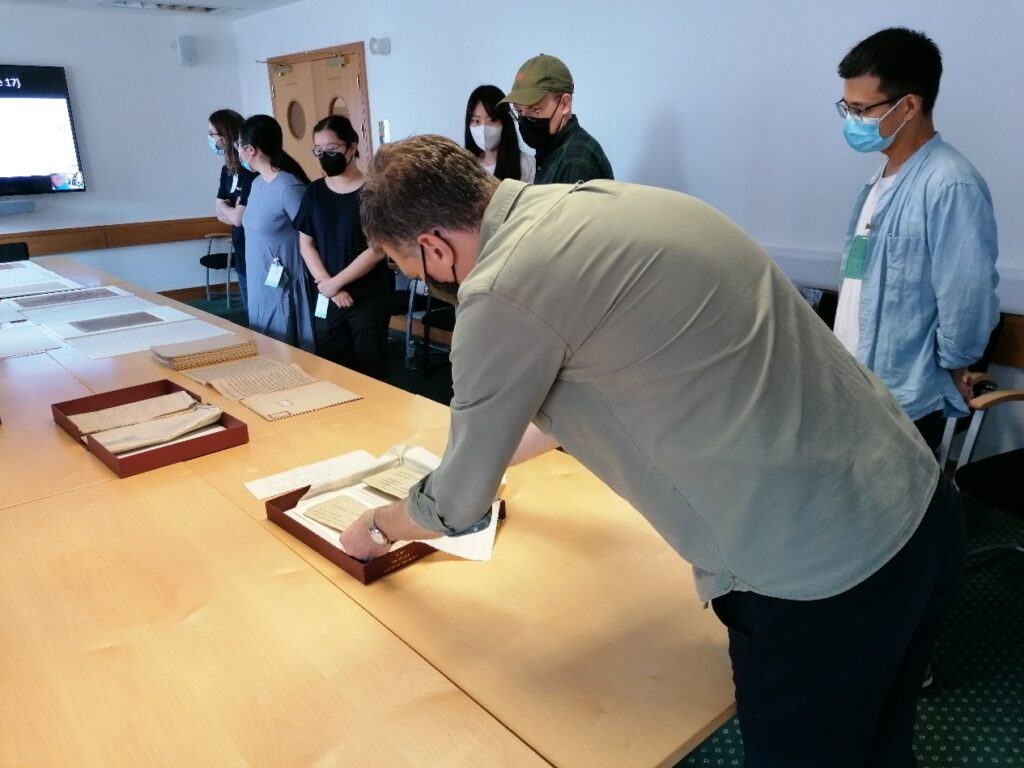

(Figure 03) Dr. Sam van Schaik unfolding a Tibetan manuscript to show the group. Republished with permission.

(Figure 03) Dr. Sam van Schaik unfolding a Tibetan manuscript to show the group. Republished with permission.

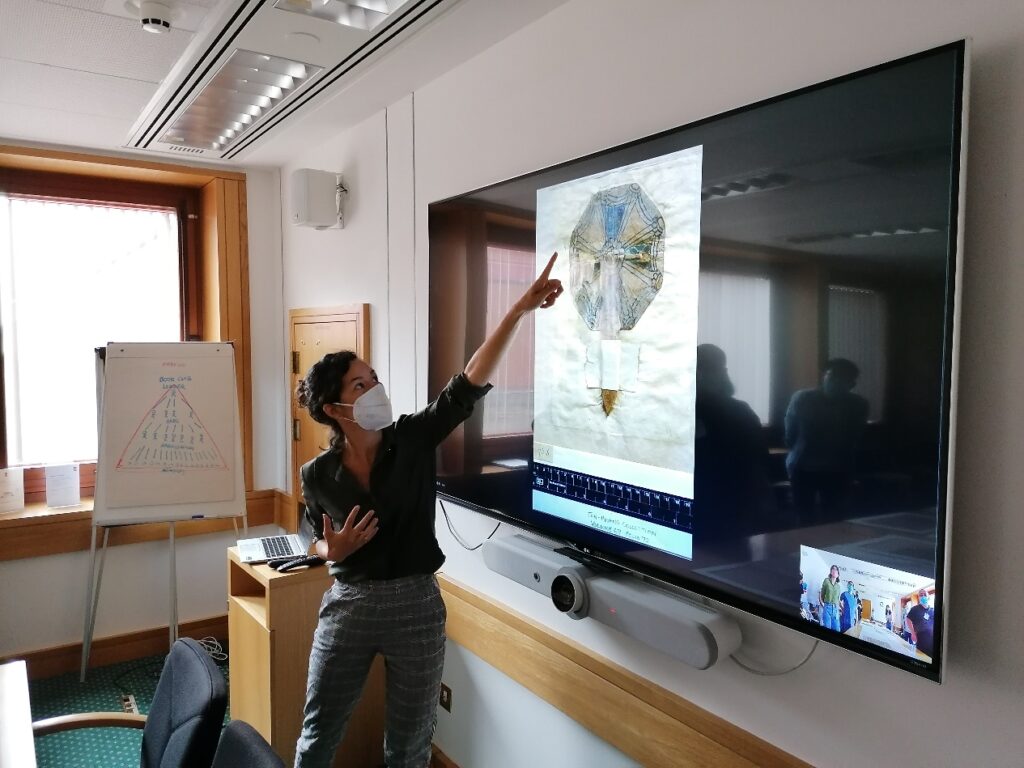

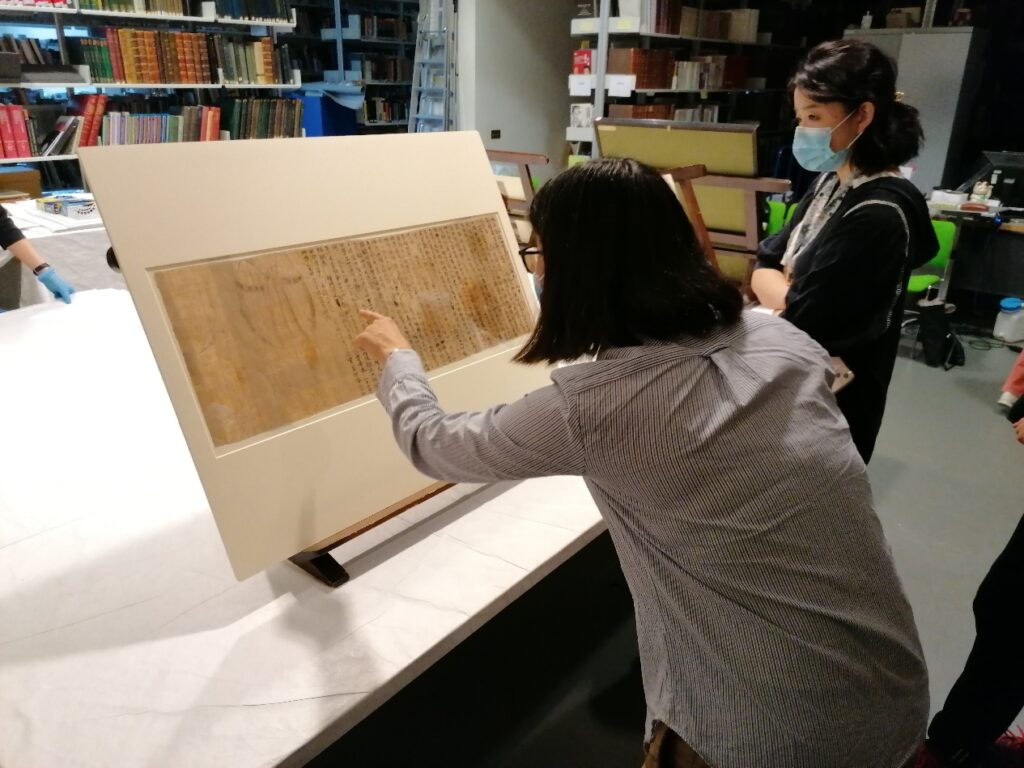

(Figure 04) Ms. Melodie Doumy pointing at the fan-shaped manuscript and explaining its possible function. Republished with permission.

(Figure 04) Ms. Melodie Doumy pointing at the fan-shaped manuscript and explaining its possible function. Republished with permission.

(Figure 05) Professor Michelle Wang explaining the ways of examining a manuscript from an art historian point of view and answering questions raised by student participants. Republished with permission.

(Figure 05) Professor Michelle Wang explaining the ways of examining a manuscript from an art historian point of view and answering questions raised by student participants. Republished with permission.

(Figure 06) Dr. Sam van Schaik introducing the Tibetan Collection. Republished with permission.

(Figure 06) Dr. Sam van Schaik introducing the Tibetan Collection. Republished with permission.

(Figure 07) Professor Imre Galambos pointing at a manuscript and explaining the punctuation and correction marks used on Chinese manuscripts. Republished with permission.

(Figure 07) Professor Imre Galambos pointing at a manuscript and explaining the punctuation and correction marks used on Chinese manuscripts. Republished with permission.

(Figure 08) Students taking notes while Professor Imre Galambos elaborates on the manuscripts on display. Republished with permission.

(Figure 08) Students taking notes while Professor Imre Galambos elaborates on the manuscripts on display. Republished with permission.

(Figure 09) Students taking their chances to examine the manuscripts before the start of the session. Republished with permission.

(Figure 09) Students taking their chances to examine the manuscripts before the start of the session. Republished with permission.

(Figure 10) Students sharing their thoughts on the possible production process of the manuscripts. Republished with permission.

(Figure 10) Students sharing their thoughts on the possible production process of the manuscripts. Republished with permission.

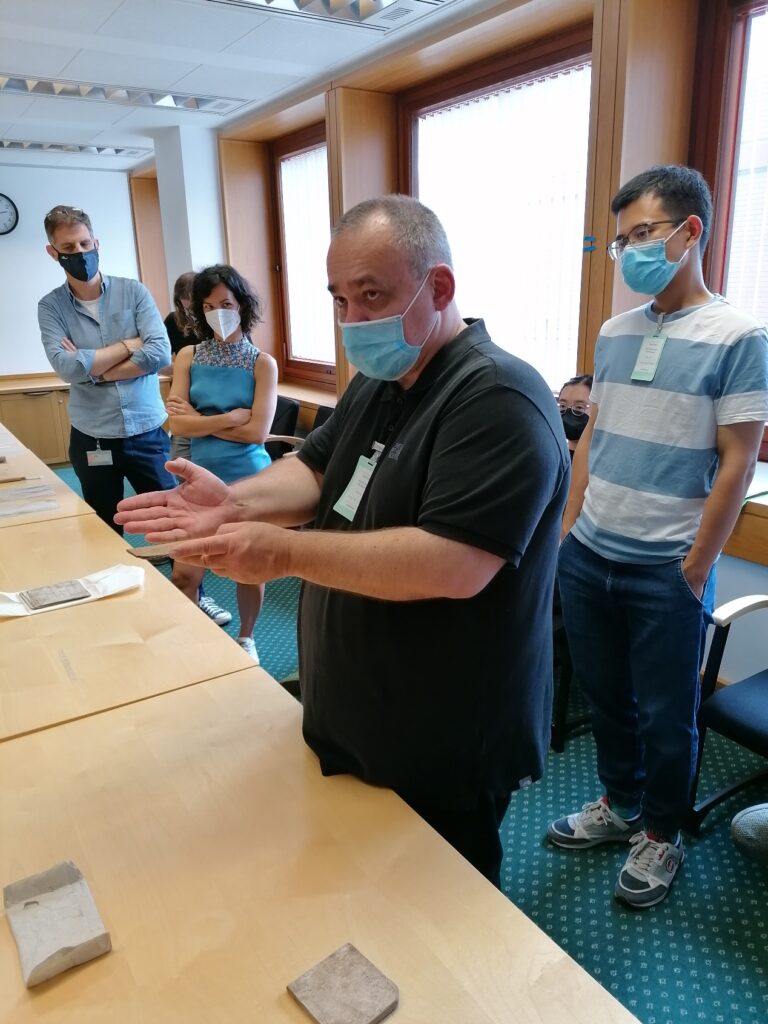

(Figure 11) Professor Imre Galambos demonstrating how the manuscripts were folded into book forms. Republished with permission.

(Figure 11) Professor Imre Galambos demonstrating how the manuscripts were folded into book forms. Republished with permission.

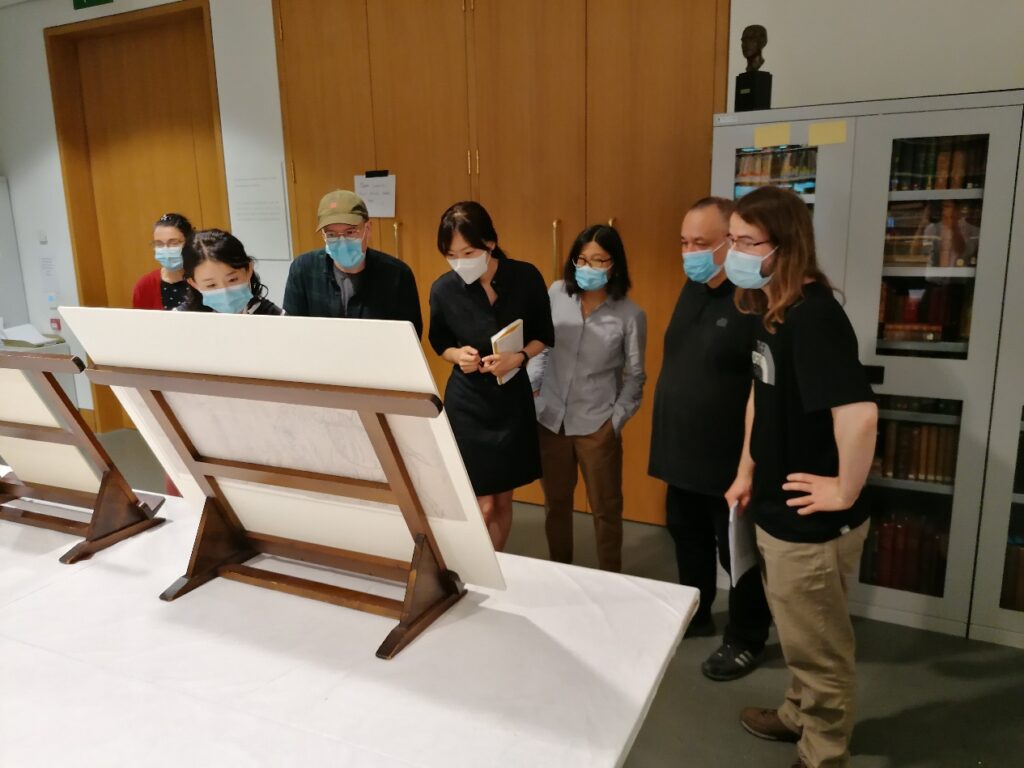

(Figure 12) Group 1 student participants examining the paintings and the images on manuscripts. Republished with permission.

(Figure 12) Group 1 student participants examining the paintings and the images on manuscripts. Republished with permission.

(Figure 13) Professor Michelle Wang explaining the manuscript. Republished with permission.

(Figure 13) Professor Michelle Wang explaining the manuscript. Republished with permission.

(Figure 14) Students taking their final glance at a painting before sharing their thoughts about its iconographical features. Republished with permission.

(Figure 14) Students taking their final glance at a painting before sharing their thoughts about its iconographical features. Republished with permission.

(Figure 15) Dr. Diego Tamburini sharing his thoughts on the colours and pigments applied to the painting. Republished with permission.

(Figure 15) Dr. Diego Tamburini sharing his thoughts on the colours and pigments applied to the painting. Republished with permission.

(Figure 16) Dr. Lilla Russell-Smith sharing her thoughts on how to appreciate this fragmented yet fascinating piece of painting with the motif of the Western Pure Land. Republished with permission.

(Figure 16) Dr. Lilla Russell-Smith sharing her thoughts on how to appreciate this fragmented yet fascinating piece of painting with the motif of the Western Pure Land. Republished with permission.

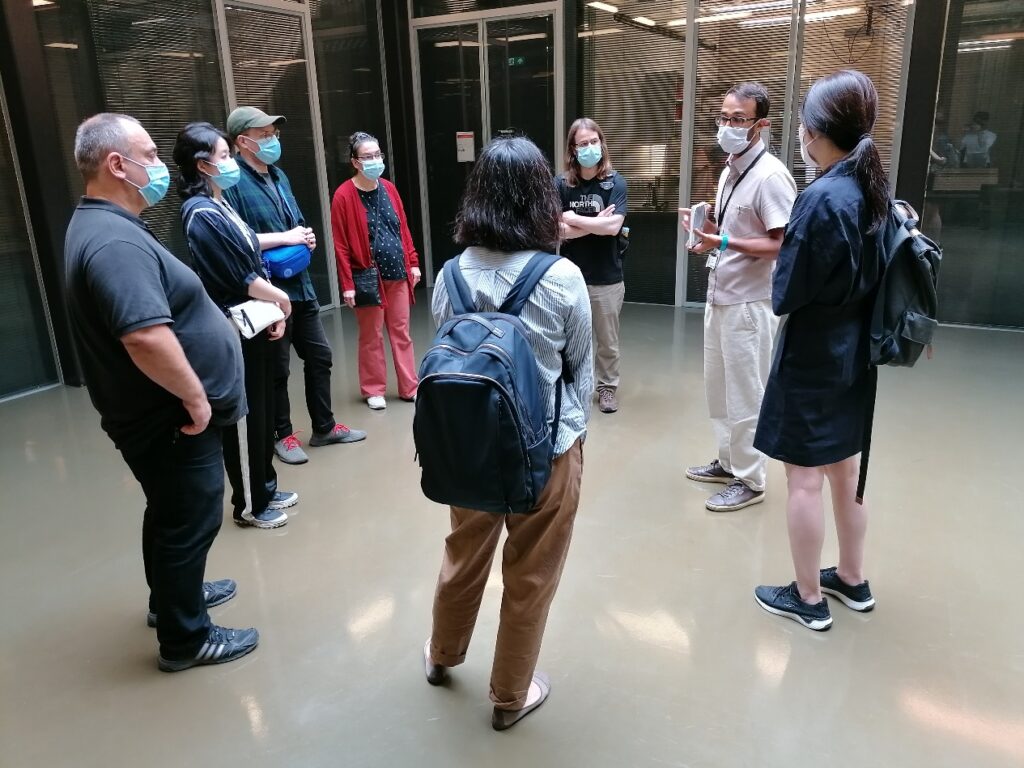

(Figure 17) A visit to the lab at the British Museum guided by Dr. Diego Tamburini. Republished with permission.

(Figure 17) A visit to the lab at the British Museum guided by Dr. Diego Tamburini. Republished with permission.

(Figure 18) Dr. Diego Tamburini explaining about the different combinations of materials and pigments used for paintings. Republished with permission.

(Figure 18) Dr. Diego Tamburini explaining about the different combinations of materials and pigments used for paintings. Republished with permission.

(Figure 19) Dr. Diego Tamburini explaining the experiment in which he would apply UV torch light on fragments to reflect the illuminative nature of certain materials and pigments. Republished with permission.

(Figure 19) Dr. Diego Tamburini explaining the experiment in which he would apply UV torch light on fragments to reflect the illuminative nature of certain materials and pigments. Republished with permission.

(Figure 20) Students examining the images of donors on the painting. Republished with permission.

(Figure 20) Students examining the images of donors on the painting. Republished with permission.

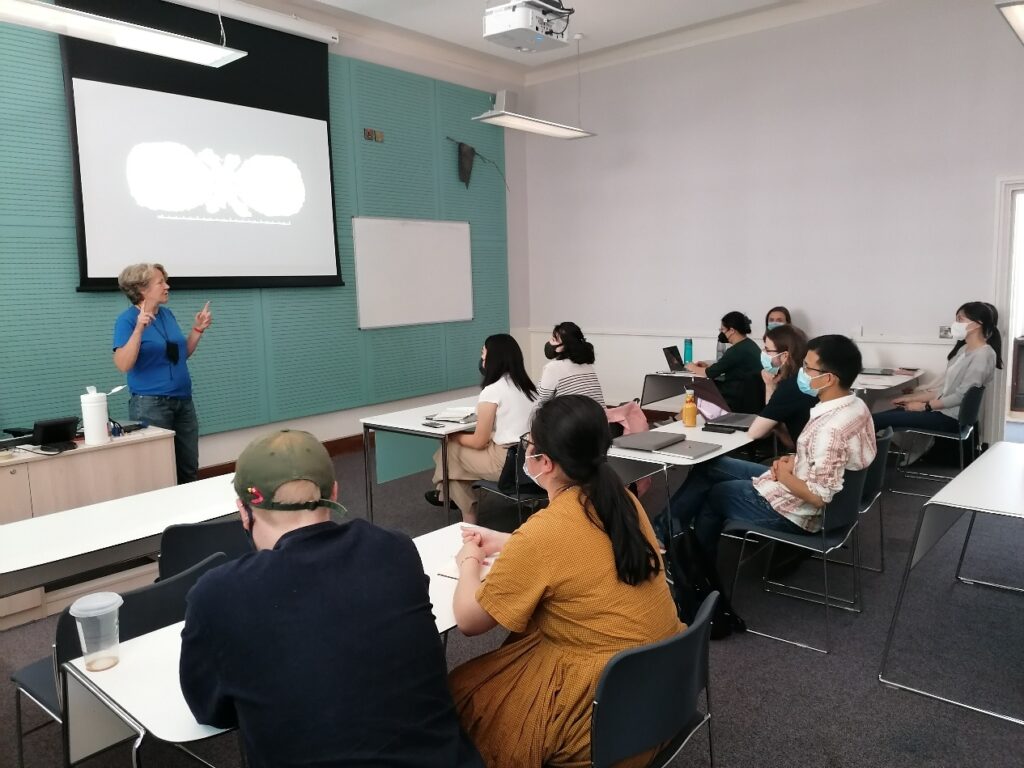

(Figure 21) Lecture by Professor Susan Whitfield. Republished with permission.

(Figure 21) Lecture by Professor Susan Whitfield. Republished with permission.

(Figure 22) Students enjoying their light meal at Russell Square and engaging in an informal chat with Professor Susan Whitfield. Republished with permission.

(Figure 22) Students enjoying their light meal at Russell Square and engaging in an informal chat with Professor Susan Whitfield. Republished with permission.

About the Author

Junfu Wong is a Ph.D. student at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge. His doctoral project seeks to explore the religious belief and ritual of lay people during the fifth and sixth centuries by analysing epigraphical texts inscribed on stone stelae. His research interests revolve around the connection between Buddhist textual and ritual traditions, the interplay between Daoism and Buddhism in premodern China, and the cultural and religious exchanges between China and its neighbours along the Silk Road and Maritime Silk Road. He recently has a co-authored book entitled Silk Road Art: Qiuci Statues published by the Zhejiang University Press.

Click here for the original posting