Written by Jiayi Zhu

From May 16 to 20, 2023, a group led by Professor Susan Andrews (Mount Allison University) and Professor Youn-mi Kim (Ewha Womans University) embarked on a field visit to South Korea, accompanied by Dr. Halle O’Neal (University of Edinburgh) and Dr. Seunghye Lee (Leeum Art Museum), and nine graduate students. The trip was supplemented by a one-day conference titled “Market, Merit, and Women” held at Ewha Womans University. This endeavor built upon the previous virtual workshop, “Working with Objects and Manuscripts”, organized by Frogbear in collaboration with Wongaksa Temple Museum 圓覺寺聖寶博物館 in the summer of 2021. The primary objective of the visit was to explore the interplay of market dynamics, merit-making practices, and the contributions of women donors in shaping East Asian religious traditions. This report presents a detailed account of the fieldwork experiences and conference proceedings.

The first day of the fieldwork, May 16, commenced with a journey to Songgwangsa Temple 松廣寺 in Suncheon. It was ten days before the Buddha’s Birthday, and strings of colored paper lanterns were hanging along the pathway leading to the temple. We first headed to their museum to see the treasures from the temple as well as a special exhibition on their stamps. The stamps are collected from Tongdosa Temple 通度寺, Haeinsa Temple 海印寺, and Songgwangsa Temple—the Three Jewels Temples of South Korea, representing Buddha, Dharma and Sangha respectively. The central government bestowed seal stamps to these larger temples, and these main temples were in charge of distributing and collecting these stamps from their branch temples. These stamps in rectangular and octangular shapes represent the authority each temple held, and were displayed together with selected sūtras, scriptures, and documents that were stamped on.

In addition to the special exhibition, we also saw their permanent collection that included a wooden portable shrine of Buddha triad, gilded wooden sūtra index boards, and relics and reliquaries from statues (bokjang 복장). The abbot and researchers at the temple museum also showed us other relics found in statues from their storage. The reliquary, textile, and clothes with dhāraṇī stamped inside, and the list of donors all showcased the close historical connection between the temple and the Joseon royal family.

Figure 1. Group photo with the abbot and researchers. Photo by Youn-mi Kim. Republished with permission.

After the museum, we spent time at the temple site. Appearing in a recent award-wining film Decision to Leave (헤어질 결심), the Songgwangsa Temple has long been acclaimed for its scenery. The path underneath the bell and drum building leads to the Great Hall with colored lanterns decorating the empty space outside. The stream surrounding the entrance reflects the bridge, the building and the flowers of the Buddha’s head (bulduhwa 佛頭花 Snowball tree) in full bloom.

Figure 2. Scenery at the Songgwangsa Temple. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Later that day, the bus took us to another temple in Suncheon called the Seonamsa Temple 仙巖寺. Because the Joseon dynasty 朝鮮王朝 (1392–1897) court discouraged any construction of Buddhist temples in the capital, Korean temples nowadays are usually found residing deep in the mountains. The path leading to the Seonamsa Temple felt similar to a hike, and on our way there, we found pillars of local protective deities, steles, and monk pagodas. Before entering the temple, we encountered the Descendance of Immortal Tower 降仙樓.

Figure 3. The Descendance of Immortal Tower. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

This two-story tower allowed visitors to enter through the supporting pillars on the ground level. Two-story towers are common at the entrance of Korean temples. For example, the drum-and-bell tower is also two-story, with the instruments on the second floor allowing visitors to come though on the first.

According to our tour guide Master Ji-an, visitors entering through the low opening of the towers’ entrance gate on the ground floor would need to bow their head, as a way to show respect to the temple and to Buddha, as they walk through it. After the Descendant of Immortal Tower, we walked on the stone Ascendance of Immortal Bridge 昇仙橋 to finally arrive at the main entrance. Although all the temples we visited are Buddhist temples, it is not rare to find traces of local religious practices or even Daoist elements at the periphery as protectors of these sites.

The Seonamsa Temple is well-known for its Wontongjeon Hall 圓通殿, or the Avalokiteśvara Hall. It became an efficacious place to pray for newborns after King Jeongjo 李昑 (r. 1724–1776) finally had a son with the help of Monk Nulam 訥庵 (1752∼1830) praying for him at this hall for one hundred days. A Buddhist master was also chanting and carrying out this ritual when we visited. And this connection to Gwaneum 觀音 (Avalokiteśvara) is still deeply rooted in the Buddhist community in Korea today.

Figure 4. A monk praying at the Wontongjeon Hall. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

We started the next day paying a visit to the Yeongamsa Temple site 靈岩寺址, which was located not far from the reed field of Hwangmaesan Mountain in Hapcheon County. It was once a Silla temple, but only a stone pagoda, a stone lantern, a pair of tortoise-shaped pedestals, and some stone structures remained today. The name of this temple first appeared in a 1014 stele that recorded Seon Master Jeokyeon’s 寂然 (932-1014) stay at the site. The Yeongamsa Temple site was excavated in 1984. The stone structures suggest there was once a covered corridor built here, indicating it used to be a large and popular temple. Because the temple was deep in the mountains, scholars speculated that it was abandoned in Joseon dynasty when Buddhism was discouraged by the court.

Unlike most temples that are facing the south, the entrance of the Yeongamsa Temple site was located on the east side, situating the temple in front of a mountain and facing a cliff. This is believed to be the best geomancy for a temple. In fact, we saw three local men walking around with gadgets in their hands locating positive chi (气) on site.

The three-story stone pagoda was made in granite with a pink tone, which is characteristic of this region.

Figure 5. The three-story stone pagoda at the Yeongamsa Temple site. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Locally sourced granite was also used to build the stone lantern between the Buddha Hall and the pagoda, forming the central axis of the temple. The lantern was installed on an elevated pedestal to be aligned with the Main Hall. This is one of the three Silla 新羅 (57 BCE–935 CE) stone lanterns with twin-lion decoration.

Figure 6. The stone lantern at the Yeongamsa Temple site. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Professor Youn-mi Kim and Master Ji-an also taught us to distinguish Silla and Goryeo 高麗 (918–1392) temples by looking at the way the stones were stacked. At the Main Hall, connecting stone was added between pillar stands to better support the wooden structure from the Silla period remained, but for the Goryeo period, there was no connecting stone and the base became higher. Buddha statues were likely to be placed in the middle of the hall for circumambulation back in the days. Although not much is left at the temple site, we learned to reconstruct from the evidence we have.

The day’s itinerary continued with a visit to the Haeinsa Temple 海印寺, where the Tripitaka Koreana is housed. The temple belonged to the Hwaeom sect, or the Flower Garland school of Buddhism. We were greeted by a master from the temple. He first led us to their museum and introduced various Buddhist paintings and statues ranging from the Goryeo to the Joseon dynasty. Then we proceeded to the entrance. Various symbols and motifs related to the ocean appeared on the way, and they were adopted and believed to be efficacious for fire protection. The crème de la crème of our visit was the storage of the Tripitaka Koreana, the world’s oldest collection of carved wood blocks used for printing.

Figure 7. Our group in front of the storage. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Over eighty thousand woodblocks were arranged neatly inside a spacious wooden building. The window panels with vertical blinds allowed the wind to blow perpendicularly through the storage, creating the air circulation that helps to keep the space cool and dry. The Tripitaka Koreana woodblocks took 1,650 carvers sixteen years to finish. And we were able to see some examples taken from the shelf.

We stayed at the temple for the evening ceremony. A group of monks took turn to play the sound instruments including the large drum and bell. The drum was beaten rhythmically with two sticks alternatively and the bell was struck by a heavy swinging wooden bell beat. The echoes of the sound rolled over the temple and the surrounding hills, creating a soul-pacifying effect that concluded our day.

Figure 8. The hall with all the sound instruments. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

On the third and the last day of our field trip, we first went to the Bongjeongsa Temple 鳳停寺 in Andong. Master Ji-an called it the museum of Korean Buddhist architecture because buildings from Silla, Goryeo, and Joseon can all be found here. Take the Great Buddha Hall as an example. The architecture is from the early Joseon dynasty, but the pedestal leading to the hall is from the later Goryeo dynasty. Buddhist temples were renovated from time to time, and the Bongjeongsa Temple shows how objects and structures from different periods form a hall and a temple.

Figure 9. The Great Buddha Hall at the Bongjeongsa Temple. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Our last stop is the Buseoksa Temple 浮石寺 in Yeongju. Unlike other temples, there is no mountain stream in front of it; instead, nine stories of stone terrace were built and the elevation of the temple requires all pilgrims to climb a lot of stairs in order to reach the Great Hall.

Figure 10. Scenery from the Buseoksa Temple. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

The Great Hall is a rebuilt from the Goryeo dynasty, but a stone dragon from the Silla is said to be buried underneath the structure. Although this is a Hwaeom temple, the main statue in the Great Hall is an Amitabha Buddha facing east, representing the Buddha sitting in his Western Pure Land. Master Ji-an explained that the temple did so for the general public, since Pure Land Buddhism has been more widely practiced among common people. To the northeastern corner of the Great Hall on the elevated terrace, there sits the Seonmyo Hall. Seonmyo was a Chinese woman who fell in love with the Silla monk Ulsang 義湘 (625–702) in China, and later became a naga that protected Ulsang in the ocean on his way back to Silla. This small hall dedicated to her shows how Seonmyo has also been regarded as the subject of worship.

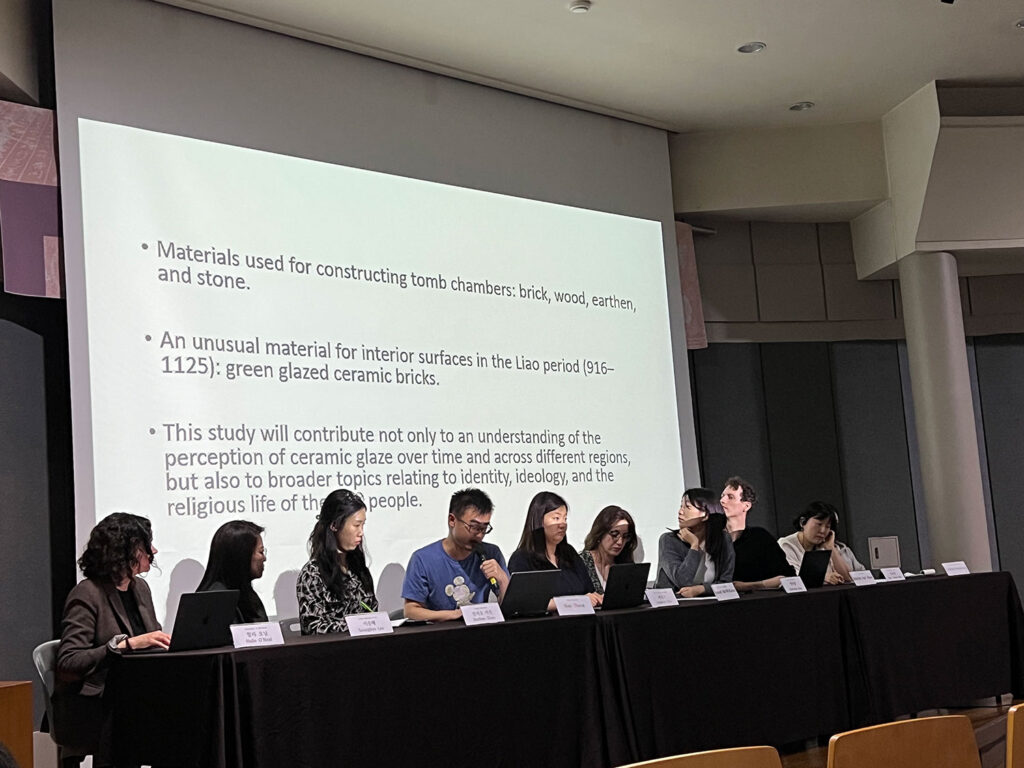

Wrapping up the visit to temples all around South Korea, we stayed in Seoul for the last two days. On May 19, Professors Youn-mi Kim and Susie Andrews organized a one-day international workshop called “Market, Merit, and Women in East Asian Buddhism”, which was co-hosted by Frogbear and Ewha Womans University Museum. Besides the group that went on to the field trip, professors and students from Ewha Womans University and other universities and institutions in Seoul also joined us in this event.

Figure 11. Workshop participants. Photo by Youn-mi Kim. Republished with permission.

Session One of the workshop in the morning featured Professor Halle O’Neal from University of Edinburgh, Dr. Seunghye Lee from Leeum Museum of Art, and Professor Yuhang Li from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Professor O’Neal presented on “The Invention of Buddhist Palimpsests: Women, Writing, and Mourning in Medieval Letter Sutras”, which was part of her forthcoming new book. She studied the practice of refashioning and recycling of the letters of the deceased by medieval Japanese Buddhists. They wrote sūtras on the letters to express their longing for the deceased, and women were most active and creative in this long-lasting practice.

Dr. Lee’s presentation titled “Royals, Middlemen, and Women: Rebuilders of Joseon Buddhist Devotionalism” brought our attention to the role of court ladies in the practice of Buddhism. Since no temple was allowed to be built in the capital, royal votive monasteries like the Bogwangsa Temple close to the capital became home to the lay Buddhist society including the court ladies. They were the main patrons of these temples during that time and Dr. Lee emphasized the importance of examining their role in the making of Buddhism during Joseon.

Professor Li, although not able to come in person, shared her research “Staging the Advent of Deities: Rethinking Empress Dowager Cixi’s Religious Practice” with the audience via video recording. She reconstructed Empress Dowager Cixi 慈禧太后 (1835–1908)’s imperial birthday celebration and showcased the various ways the Empress Dowager was portrayed as Guanyin Bodhisattva in this event. Many workshops collaborated in the staging and acting of the auspicious omens as well as the making of papier-mâché and Dharma boats that have religious signification.

Speakers in Session Two in the afternoon were Professor Youn-mi Kim from Ewha Womans University, Professor Jinchao Zhao from Tongji University, and Professor Susie Andrews from Mount Allison University.

Professor Kim presented on “Textile, Talismans, and Incantation: Tracing Female Agency in Joseon Buddhist Practice” that shed light on the practice of burying clothes in tombs. Clothes from these Joseon tombs are often found with Buddhist prayers, incantations, or wishes written or stamped on them. Even in the tomb of the Confucius scholar Chŏng On 鄭溫 (1481-1538), his wife offered her garments with Buddhist prayers on them. As Professor Kim argues, women might have chosen the medium of clothes because they were more familiar and comfortable with it.

Professor Zhao introduced us to “Commission and Perception: Buddhist Stone Pagodas from the 6th-century Shanxi China”. More than four hundred pieces of stacked stone pagodas dated to the sixth to the eleventh century were found in pits from Nanyanshui in Shanxi Province. Although there have been case studies of these stone pagodas, Professor Zhao had studied them as a group for their larger implications. She approached these stone pagodas from three angles namely architecture, imagery, and production. By doing so, she found out that these pagodas shared collective patronage, and individual image unit was available to be commissioned. She also emphasized that women patronage could be identified by the names inscribed.

Professor Andrews concluded the presentations by reflecting on “Teaching ‘Markets and Merit’ with and for the Frogbear Database of Religious Sites in East Asia”. She gave examples from her pedagogical expertise as well as from our trip to illuminate on how we can all contribute to a more inclusive and caring learning environment.

After the presentations and Q&As, two roundtables of graduate students from North America and Korea took place. The nine graduate students from this field visit joined Korean students to share our dissertation and research on East Asian Buddhism and Buddhist art. The topics range from Japanese temple museums to printed books on the Buddha’s life from the Qing dynasty 清朝 (1644–1911). All students benefited from the exchange and discussion on their works.

Figure 12. Professors and students at the roundtable. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Since it was right before the Buddha’s Birthday, some of us went to see the decorated lanterns at the Gwanghwamun Plaza in celebration of this festival. Papier-mâché of Buddhist deities like Avalokiteśvara and the four guardian kings as well as Buddhist symbols like lotus flower, bell, and pagoda radiated in the moonlight, and gave a perfect ending to our one-day workshop.

Figure 13. Decorated lantern of Avalokiteśvara. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

The last day of our field visit was packed with museum trips. We first went to the Leeum Museum of Art, where Dr. Lee greeted us and led us on a guided tour of their Korean Buddhist art collection. Some highlights were two Goryeo Buddhist paintings, an illustrated manuscript of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra from the Silla dynasty, and a Goryeo gilded miniature pagoda.

Figure 14. The gilded miniature pagoda from Goryeo. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

We also spent some time looking at the special exhibition Joseon White Porcelain: Paragon of Virtue (조선의 백자: 군자지향).

Our next stop was the National Museum of Korea. They organize their collection of Korean Buddhist art based on different medium, and there are separate rooms for Buddhist paintings, stone statues, and metal works. On the first floor was a ten-story stone pagoda from Gyeongcheonasa Temple 敬天寺址 dated to the Goryeo dynasty that goes up to the museum’s second and third floors.

Figure 15. The ten-story stone pagoda from Gyeongcheonasa Temple. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

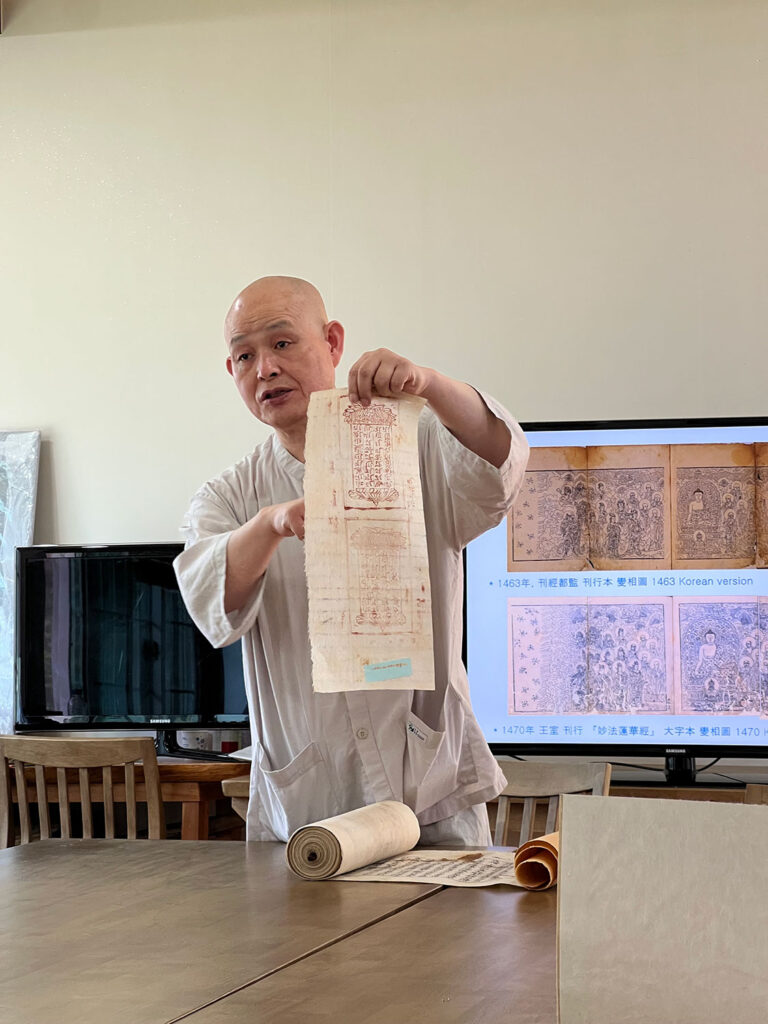

In the afternoon of May 20, we went to our last stop of the day and of the trip, the Wongaksa Temple Museum in Goyang. Venerable Jeonggak 正覺, who was with us at the online training session in summer 2021, welcomed us and generously presented his collection of Buddhist manuscripts, prints, and paintings. He first introduced us to each of the pieces, and then the objects were passed around so we had great hands-on experience examining these works of art.

Figure 16. Venerable Jeonggak showing his collection. Photo by Jiayi Zhu. Republished with permission.

Some highlights of his collection include one of the earliest prints from the Tripitaka Koreana, rare metal carved scriptures, and printed and stamped dhāraṇī from the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties.

Figure 17. The group handling the objects. Photo by Youn-mi Kim. Republished with permission.

Besides the manuscripts and prints, objects like miniature terracotta pagodas with holes underneath them for rolled-up sūtras, woodblock from the early Joseon, and chief monk’s stamps that Venerable Jeonggak prepared all helped us to gain a deeper understanding of the production process of these pieces. After visiting all the temples and seeing all the architecture, the afternoon we spent with Venerable Jeonggak working with smaller-scale objects allowed us to reflect on the trip and connect the objects we saw at museums back to their original context.

Figure 18. Group photo with Venerable Jeonggak at the Wongaksa Temple. Photo courtesy of Youn-mi Kim. Republished with permission.

The Market and Merit Field Visit concluded at the Wongaksa Temple, resonating with the online training session we received from Venerable Jeonggak two years ago. But in light of the roles of women donors in the making of religious life, we were able to see and experience much more beyond these objects and manuscripts. The fieldwork experiences provided firsthand encounters with tangible artifacts, rituals, and historical narratives, enriching our understanding of the cultural and religious heritage of South Korea. The conference served as a catalyst for further exploration and collaboration, inspiring future research endeavors in the agency of women in the long history of Buddhism in East Asia. Our field visit ended here, but the exploration of the essential role female practitioners played in the making and remaking of Buddhist practices has just started.

Author Bio:

Jiayi Zhu is a PhD candidate in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilization at the University of Chicago. She is interested in medieval Buddhist ritual and art in East Asia. Her dissertation examines the materiality of dhāraṇī practices in the 10th-century. Jiayi looks at the production of dhāraṇīs prints and amulets, sutra pillars and stone pagodas that bear dhāraṇī inscriptions and the widespread narratives surrounding them to reconstruct the popular beliefs and ritual practices on dhāraṇī sutras around this transitioning time in East Asia including Five Dynasty China, late Unified Silla Korea and late Heian Japan.

Click here for the original posting