By Longyu Zhang, Ghent University

The “Image – Text – Reality in Buddhism: Interrelation & Internegation” workshop and the related fieldwork activities, belonging to the research cluster 3.4 of the FROGBEAR project, convened virtually from May 23 to May 31, 2022.

Three-Day Conference

The first part of the activity, a three-day conference, was organized by Prof. Christoph Anderl (Ghent University) and Dr. Polina Lukicheva (University of Zurich).

Figure 1 Prof. Christoph Anderl (left) and Dr. Polina Lukicheva (right). Republished with permission.

Figure 1 Prof. Christoph Anderl (left) and Dr. Polina Lukicheva (right). Republished with permission.

Dr. Lukicheva provided the first introductory lecture on May 23 entitled “Forms of Presentation of Meaning in Buddhist Teachings”. She focused on the meaning and significance of a particular form of representation, mainly in the context of specific Buddhist doctrine and images. This lecture consisted of three major parts: theoretical background, case studies of texts, and parallels in images. In the first part, Dr. Lukicheva clarified that a common assumption that texts and images represent existing objects and their relations are based on the paradigm that assumes external world as consisting of a plurality of objects and emphasizes dualism such as: differentiating perception and representation, observer and observed objects, internal and external, etc. But texts and images can not only be understood as representations of something given out there but also as derivative from the (cognitive) functions that bring the appearance of objects about. This understanding allows to transcend the dualist model of reality and accords with an “optimistic” position developed within Buddhist teaching. That is to say, representation is made possible by the realization that ultimate reality is precisely identical to the phenomenal world in how it unfolds in the phenomenal process of arising.

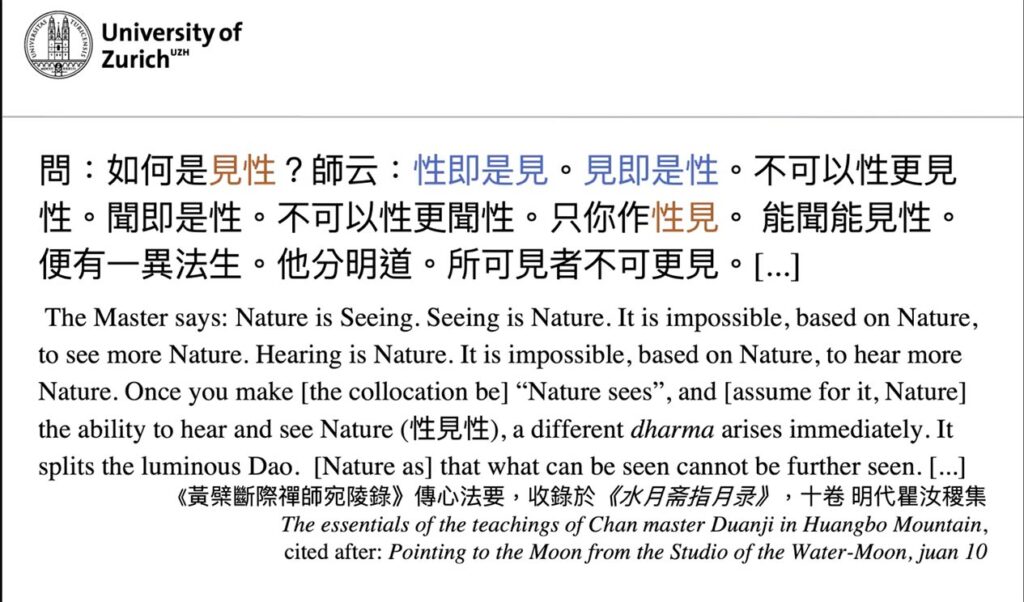

The second part focused on analyzing examples from texts written by literati and lay Buddhists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as examples from Buddhist treatises referred to in the litetrati’ texts. Dr. Lukicheva chose the period mentioned above because it was very productive in terms of the synthesis in the developments of the theory of images and artistic practice with a stark impact of Buddhist thought. Extracts from Chan collections were shown as examples, with an emphasis on the word jianxing 見性 in “The essentials of the teachings of Chan master Duanji in Huangbo Mountain” (Huangbo duanji chanshi wanling lu 黃檗斷際禪師宛陵錄) written by Qu Ruji 渠汝稷 (1548–1610).

Figure 2 The extract from “The essentials of the teachings of Chan master Duanji in Huangbo Mountain”. Slide by Polina Lukicheva. Republished with permission.

Figure 2 The extract from “The essentials of the teachings of Chan master Duanji in Huangbo Mountain”. Slide by Polina Lukicheva. Republished with permission.

In the text, Jian 見 (seeing) is a metaphor for the process of knowing the absolute and fundamental reality called enlightenment. But for an ordinary understanding, seeing is a process between a subject and an object. Something sees another thing, and something, including something invisible to the naked eyes but supposed to exist such as Buddha-nature, is seen. The thing that can see is supposed to exist as well. The expression jianxing occurred in several versions of the Nirvana sutra and was especially popular in the Chan tradition. There are different combinations of jian and xing in the extract, which are used in order to reveal the “loop structure” of the relations between the subject and object. The “word game” of swapping the words here indicates that enlightenment cannot be achieved as long as the process is conceived in terms of a subject-object relationship. The subject-object structure leads to a paradox, and the realization of this paradox should lead to the realization of the identity of nature and seeing.

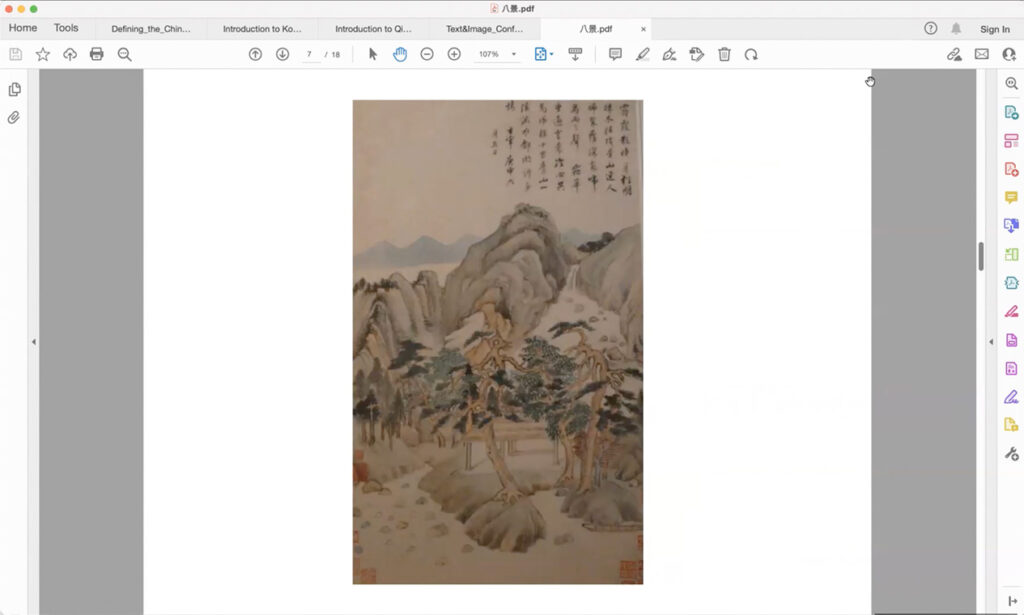

Last but not least, Dr. Lukicheva demonstrated how the interpretation mentioned above can be applied to analysis of images. She stated that the temporal and spatial orders in the pictorial structures in the literati paintings of the 17th century indicate that image was understood not as a representation of some external reality, but rather as representation of the process of how phenomenal reality emerges. Eight Views of Autumn Mood (qiuxing bajing 秋興八景) drawn by Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636) was the focus of this part.

Figure 3 Eight Views of Autumn Mood (the sixth painting). Slide by Polina Lukicheva. Republished with permission.

Figure 3 Eight Views of Autumn Mood (the sixth painting). Slide by Polina Lukicheva. Republished with permission.

In each leaf, Dong Qichang rearranged the spatial order and temporal structure, so that the unique embodiment of the moment in which this image emerged could be achieved. To show the water running fast, Dong Qichang squeezed the far and the near together, creating intensity within the image. To deliver peace and eternity, he changed the spatial structure into a vaster one. The verses in these paintings can mutually confirm the structures. Aside from the different internal structures, various layers contained in every leaf were synthesized into a single landscape image and a unified event of the experience. These images display a momentary but absolute instance of existence. Dr. Lukicheva called it the “suspended moment”. Such representation of the moment is in correspondence with the concept of yinian 一念 in Buddhism. Yinianrefers to a momentary thought insight, breaking through an ordinary spatial and temporal structure, but nevertheless identical with the experience of the phenomenal reality.

After the introductory lecture, fifteen scholars gave lectures on both theoretical research and case studies of the relationship between Buddhist texts and images throughout the next three days.

On the second day (May 24), a one-hour roundtable discussion was open to all scholars giving lectures and to registered participants.

The discussion began with several theoretical questions because previous lectures centered more on philosophical and theoretical issues. Dr. Lukicheva raised a question about how texts and images can refer to ineffable, i.e., the absolute reality and abstract concept. Prof. Anderl understood this question more practically. He stated that the practical use of these texts and images was also important besides philosophical meanings. The way of using them and the functions that people expected from them can partly determine the content and format of texts and images. In addition, they are not only the result of doctrines and people’s intentions but will also influence people’s experience when practicing. He then emphasized that researchers need to pay attention to practical features, especially when studying Buddhist sites in the Sichuan region. For example, many tableaus in the Sichuan region were constructed as bevels inclining toward audiences, enabling audiences to see the content even on the upper parts of tableaux.

Dr. Rafael Suter (University of Zurich) put forward a question related to his study on “Essay on the Golden Lion” (Jin shizi zhang 金獅子章). He wondered whether this essay has any practical use since it contains some elements of reality, although it is usually considered a philosophical text. He also mentioned the possibility that the text was first used for practical purposes but then was influenced by the scholastic tradition, which turned it into a philosophical text. However, the question still needs an answer due to the lack of visuality of this text.

Dr. Lukicheva then raised the question of understanding the analogy between the abstract concept and visualization, which sparked many discussions. Prof. Anderl commented that visualization does not need an abstract concept but only needs the analogies which point to it. Dr. Henry Albery (Ghent University) stated that abstract items of doctrines often become narrative when they are rendered. The language conveying the abstract concept is not the concept itself. There must be analogies from ineffable abstract concepts to audible/visible languages or texts. He took the visualization of the concept “compassion” as an example. Compassion in a practical Buddhist context is usually depicted as a normative set of behaviors derived from someone who has compassion, so compassion becomes performative. Thus, the depiction of compassion becomes an analogy being manifested physically.

Sau-Ling Wendy Yu’s comments could serve as a good summary of the theoretical discussion. She stated that the transition from the original texts to texts in other languages and from texts to images might cause a certain degree of distortion and ambiguity. The functions of images are diverse. Therefore, it is not so easy to research the relationship between texts and images.

In terms of research on practical aspects, Massimiliano Portoghese drew attention to human agencies standing behind the images. Who made these images, and what is their relationship with monastic communities? Prof. Anderl responded that there were official documentations of some practical things carried out during the construction of caves or murals in Dunhuang, such as division of labor and payments. Those who made these images were highly professional, and their relationship with the monastic community, which was influenced by donations, changed in different periods.

Afterwards, Elizaveta Vaneian asked whether monks created specific important images that were later widely spread. Dr. Albery stated that there was not enough evidence for such a phenomenon, but he gave a few examples indicating that the answer might be no. In Gandhāra, some great artists became monks, usually giving up their professional jobs. Prof. Wendi Adamek (University of Calgary) added that some creators of caves, such as an inscription in Daliusheng 大留聖cave, wanted to record their names there. These cases are different from official inscriptions but can serve as a source to find the identity of creators. Although it was not possible to answer all the questions raised during this period, this roundtable discussion allowed all the participants to get a deeper understanding of previous lectures and put forward new ideas as well.

On the third day (May 25), Prof. Anderl gave the final lecture, “Techniques of textual adaptation to local spaces” that focused on the transformation of texts and the interaction between texts and images. At the beginning of the lecture, Prof. Anderl elaborated on how he understood narrative: a fluffy and soft thing. Despite the “hard” core of the narrative, which enables a narrative to be different from others, peripheral elements are very flexible and usually shift or develop along with local spaces, including concepts, ideological frameworks, and materials. Based on the soft features of the narrative, it is possible to research how certain narrations change in different areas. He took Śyāma jataka as an example. This jatakawas popular in the Maijishan麥積山 and Dunhuang areas, which was ruled by non-Han people during certain periods. Horses, hunting parties, and other similar elements, which were especially important to non-Han people, were a large focus in these areas. In addition, Prof. Anderl emphasized that Sichuan was a wonderful place to conduct such research on vernacularization due to its complexity.

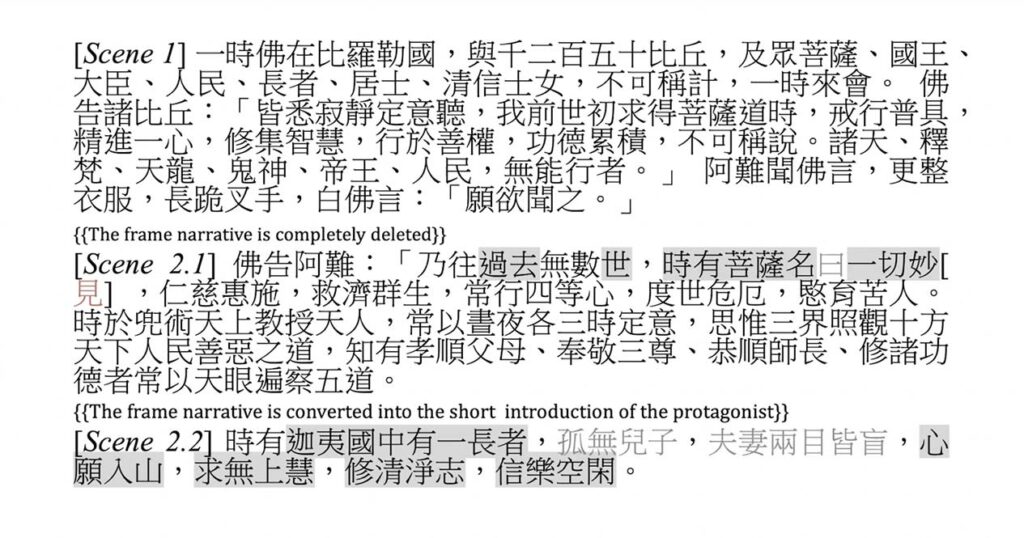

After this introduction to the background of narrative, Prof. Anderl then illustrated one technique used by Shi Daoshi 釋道世 in Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 to transform the text of Śyāma jataka. He compared the content of Śyāmakajātaka-sūtra (Foshuo Pusa shanzijing 佛說菩薩睒子經) and found that the transformation was very simple and direct in extracting the characters and sentences, and he put them together without much creative work. Most of the content was simply omitted. This is one technique that was probably not previously noticed by scholars. Prof. Anderl marked the extracted content in a shaded color and some rephrased sentences in light gray to make the new text more readable and understandable.

Figure 4 The marked text of Śyāmakajātaka-sūtra. Slide by Christoph Anderl. Republished with permission.

Figure 4 The marked text of Śyāmakajātaka-sūtra. Slide by Christoph Anderl. Republished with permission.

The method seems very easy, but there must have been much understanding and practice behind it. The extracted sentences are usually the core elements of the narrative or the most important parts that fit the text’s purpose. Deleting characters not only changes some content but sometimes also changes the language structure. For instance, some disyllabic words were reduced to monosyllabic words. Such adjustments are not isolated. The author needed to reduce the content proportionally to maintain the rhythm of the text. A few changes also reach the grammatical level. In the scene 8.3, the structure “verb1 + object2, verb2 + object2” was contracted into “verb + object (1+2)”. It is Chinese, with its immediate constituent structure and its lack of grammatical morphology, that allows certain mechanical techniques of textual adaptation. Otherwise, the text must undergo complex rephrasing.

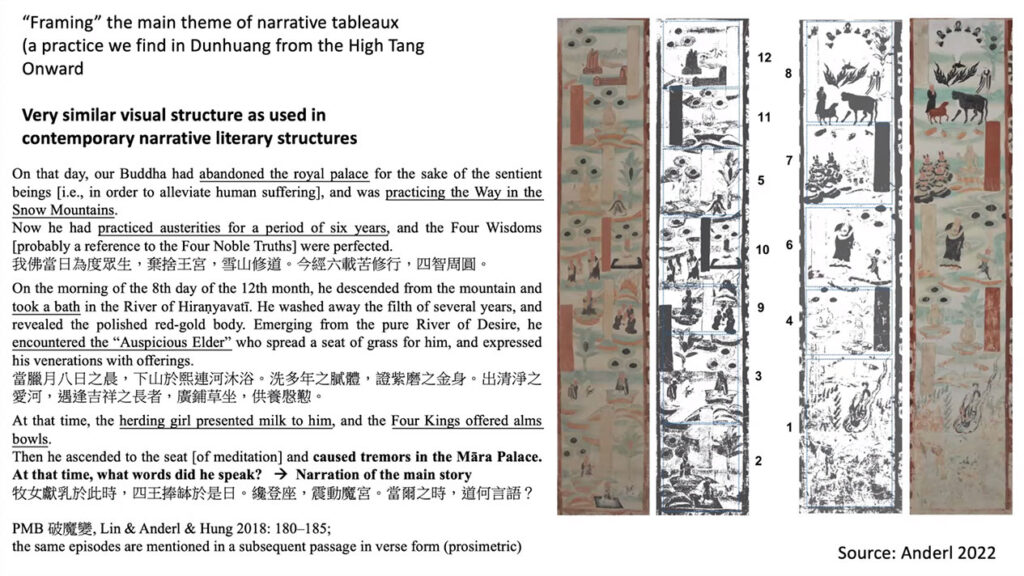

Regarding the interaction between texts and images, Prof. Anderl stated that the textual programmatic embedding would influence the visual embedding and illustrated this opinion with manuscripts, murals, and carvings. The manuscript is the visuality of the text itself, and much information disappears in the processed and edited text, such as the calligraphy style, the quality of the paper, the visible structure of texts, and vernacular and phoneticized characters. In one leaf of the Dunhuang manuscripts, there are also two special symbols, which might be the visuality of the content but without solid explanation embedded in the text. Some non-canonical contents also appear, probably under the influence of local materials. Therefore, the most important keyword for this case and also for the Anyue site is vernacularization, which can transform the original contents into other registers. Another example is the mural “Māra’s Attack and Temptation” in the Yulin No. 33 cave. There are twelve scenes painted on the side panels. These twelve scenes are in a “confusing” sequence if one only sees the mural. However, its visual structure is similar to the structure used in the contemporary vernacular literary “Destruction of Māra Transformation Text” (Pomobian 破魔變).

Figure 5 On left, textual excerpt from Destruction of Māra Transformation. On right, mural panels in Yulin No. 33 cave. Slide by Christoph Anderl. Republished with permission.

Figure 5 On left, textual excerpt from Destruction of Māra Transformation. On right, mural panels in Yulin No. 33 cave. Slide by Christoph Anderl. Republished with permission.

In the last part, Prof. Anderl discussed how Śyāma jataka was represented in the Baodingshan 寶頂山. The narrative is integrated into the tableau of the Transformation of Buddha’s Practice of Filial Piety Sutra (Dafangbian fo bao’en jing 大方便佛報恩經), which Prof. Karil Kucera introduced on the second day. The story of Śyāma is reduced to one important scene (most relevant to the theme of the tableau) in which Śyāma asked the Buddha to take care of his parents. Furthermore, the inscription of the scene rephrases Śyāma’s story in a concise but complete way and with vernacular features so that common people can understand the content as well. Prof. Anderl also briefly introduced the Mahāsattva jātaka. The scene represented in the tableau is not the core plot as in other Buddhist sites, and it is hard to understand its relationship with filial piety without the inscription. Therefore, the text, in this case, is indispensable.

Above all, Prof. Anderl concluded that the adaptation happened on multiple levels, including both textual and image. And sometimes, only when these two media merge, can interpretation be possible.

Fieldwork Activities

The second part of this cluster’s activities was a combination of fieldwork and processing metadata. The fieldwork centered on Buddhist sites in Anyue county in Sichuan province, including Yuanjue dong 圓覺洞, Pilu dong 毗盧洞, Wofo yuan 臥佛院, Kongque dong 孔雀洞, and Qainfo zhai 千佛寨. It is still impossible to conduct fieldwork in China this year due to the pandemic. Therefore, FROGBEAR adapted the format of this activity in a virtual way. International researchers and students were divided into five groups according to their time zones, and every group covered one Buddhist site. They studied high-resolution images taken on previous field trips, extracted details from photos, and wrote descriptions for the FROGBEAR Database of Religious Sites in East Asia.

Before the actual start of fieldwork, Prof. Yang Xiaodong (Sun Yat-sen University) and Prof. Bruce Rusk (University of British Columbia) gave two lectures on basic information about Sichuan Buddhist art and the FROGBEAR database on May 26.

Prof. Yang focused on basic historical developments and the artistic expression of Buddhist art in Sichuan.

Figure 6 Screenshot of Prof. Yang Xiaodong’s lecture. Republished with permission.

Figure 6 Screenshot of Prof. Yang Xiaodong’s lecture. Republished with permission.

The history can be divided into three stages. The earliest stage started in Leshan 樂山, where a very old Buddhist image was found. The image possibly dates back to the late 2nd or early 3rd century and is the most crucial evidence to prove that Buddhist elements emerged in this area, since there was no relevant documentation in textual form during this period. It is worth noting that the image appears together in a tomb with images of folktales and Taoism. There are no systematic representations of Buddhism. Therefore, the image indicates that some Buddhist elements were introduced into this area, but people knew nothing about the religion. The second stage began in the late 4th or early 5th century. An important stele was found in Maoxian 茂縣 as concrete evidence that people of that time developed some knowledge of Buddhist doctrines and Buddhism as a religion. There is a Buddha-like figure and a stanza next to it on the stele. The stanza was extracted from the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāna Sūtra. The story in this stanza, a jataka about ascetic practice, was very popular in East Asia. It can be found in several Japanese pagodas and at Baodingshan as well.

The third stage of the historical development of Buddhist art is when Buddhism flourished in the Sichuan region from the 5th century onwards. Prof. Yang gave three crucial pieces of evidence found in Chengdu 成都. The first is the image of Amitābha accompanied by fifty Bodhisattvas (Emituo fo wushi pusa xiang阿彌陀佛五十菩薩像). It was a typical iconography that also appeared in Dunhuang 敦煌, Longmen 龍門, and other sites in Sichuan. The second evidence is the Indic-style image of Aśoka found in Wanfosi 萬佛寺, which indicates the relation between the Sichuan basin or Chengdu plain with Southeast Asia. The carving of the Kaibao Tripiṭaka (Kaibaozang 開寶藏) in Wanfosi is also the first xylographic reproduction of canons in Chinese Buddhism history. Furthermore, different Buddhist traditions and even local beliefs were integrated in the third period. Baodingshan is a complex with a series of small Buddhist sites showing strong vernacular features. Besides, there are elements of Tibetan Buddhism in this area, such as the Qianfoya 千佛涯 in Guanyuan 廣元, which demonstrates another origin of Buddhism in Sichuan in addition to Southeast Asia.

After some basic history, Prof. Yang elaborated on three prominent features of Sichuan Buddhist art: canonicity, localness, and syncretism. Stone scriptures, besides the carving of Kaibao Tripiṭaka, were introduced as an example of canonicity. The stone scriptures were a combination of two traditions: one is the Chinese tradition of carving Confucian texts in stone, and the other is the Indic tradition of the Mahāyāna book cult. Stone sculptures, usually on pagodas in the Anyue 安岳 area, are mostly of catalogue literature (jinglu 經錄), i.e., recording the titles of scriptures which served as the symbolic canon and Dharma śarīra. In terms of localness, Baodingshan would be a wonderful case. While it is too complex to introduce the Liu Benzun 柳本尊cult in a short time, Prof. Yang raised instead the issue of Qianfodong 千佛洞 at the Pilu dong site. All the small buddhas in roundels were carved with different objects held in their hands, which might represent local features. For instance, there is one Buddha holding a leaf-like thing. This image probably relates to the local tradition of writing canons on palm leaves. Last but not least, Prof. Yang talked about the syncretism of Sichuan Buddhist art. He explained that syncretism referred not only to the integration of distinct religions but also to the integration of different Buddhist traditions, such as the Tibetan/Esoteric elements in Sichuan Buddhism. The cave containing both Buddha and the Jade Emperor 玉皇 in Miaogaoshan 妙高山 and the tableau of the Transformation of Buddha’s Practice of Filial Piety Sutra in Baodingshan are typical examples as well.

Prof. Yang’s lecture provided basic information on Sichuan Buddhist art for participants who did not have much knowledge in this field. In addition, he used vivid examples along with some appliable methods to demonstrate his ideas, which helped all participants to expand their methodology when conducting such research.

Afterward, Prof. Bruce Rusk delivered a lecture on more practical issues relating to metadata, which was the major task for participants in the fieldwork.

Figure 7 Screenshot of the lecture’s title page. Slide by Bruce Rusk. Republished with permission.

Figure 7 Screenshot of the lecture’s title page. Slide by Bruce Rusk. Republished with permission.

He first briefly introduced the FROGBEAR Field Visit Data, an open and publicly accessible data containing more than 900 records of materials with relevant information accumulated from fieldwork in East Asia. There are two ways for accessing the data. One is through the FROGBEAR Database of Religious Site interface, and the other is through the UBC Library Open Collection. Information on how to use the database can be accessed through the webpage: https://frogbear.org/frogbear-database-of-religious-sites-in-east-asia/. It is helpful to see a map display which provides a geographical overview of all the East Asian Buddhist sites based on the recorded entries in the FROGBEAR interface.

Prof. Rusk then explained why metadata was necessary and where the metadata came from. Scholars usually take a lot of pictures of significant sites and specific elements in fieldwork. Without metadata, no one can easily find or identify the multitude of photos, even if they are accessible online. The task for participants concerning this activity is to add important information to these photos, such as the contents, origins, and relevant concepts. The automatically generated metadata by the computer or camera can provide most of the information, such as the file names, date and time, and the location. However, the most challenging work for participants is to provide descriptions that are suitable for both scholars and the public.

In the last part, Prof. Rusk elaborated on how to produce well-structured and meaningful metadata. Participants need to get an overall understanding of the data before they create records. How many images will an entry include? What is the most important or interesting element in them? What critical information should be conveyed? All these questions need to be answered to make records more comprehensive and coherent. Prof. Rusk later explained how every column in the metadata sheet should be filled in and answered some relevant questions to help making subsequent work clearer and more manageable. Furthermore, he reminded all participants that digital humanity is a significant issue when doing computer-related work. During the activity of producing metadata, everyone should pay attention to recognizable people in the images. Such images cannot be included in the database without those individual’s consent to protect their privacy. However, as an alternative, people’s faces may be blurred with the help of a special application in order to be included in the database.

In addition to scholars’ lectures, MA students at Ghent University, who attended the course “Buddhism: Text and Material Culture”, also prepared introductory essays with relevant images for five sites based on the course content and existing research. Participants could download and read them on the Ufora website (https://www.ugent.be/ufora) in advance to obtain a basic knowledge of these sites.

The virtual fieldwork began on May 27. Ghent MA students joined the virtual fieldwork to assist workshop participants with essential information and practical work. Every group had a designated location and the group members worked four hours together each day in Zoom meeting breakout rooms, including discussion and individual work. Group 1 (Qianfo zhai) and 2 (Pilu dong) participated from CET 10:00 to 14:00. Group 3 (Wofo yuan), 4 (Yuanjue dong) and 5 (Kongque dong) met from CET 16:00 to 20:00. Prof. Anderl supervised the whole process during all five days. Some scholars attending the conference, such as Prof. Suey-Ling Tsai, also joined the discussion of some groups.

Prof. Anderl arranged four specialist sessions on May 28 and 30, considering that the sites mentioned above have not been thoroughly researched, and participants might encounter many problems when writing descriptions. Prof. Yang Xiaodong (covering all sites), Dr. Dong Huafeng (Sichuan University, covering Pilu dong), Dr. Li Fei (Sichuan Antique Archaeology Academy, covering Wofo yuan and Yuanjue dong), and Dr. Zhang Liang (Sichuan University, covering Qianfo zhai and Kongque dong) answered numerous questions relating to Buddhist history and specific carvings and statues. They provided some of the latest research outcomes as well. Prof. Rusk also gave guidance and suggestions on the ongoing metadata sheets.

All groups had two joint meetings on May 29th and 31st, when participants shared their working progress and experiences. For example, Group 1 shared their method to identify and describe the tableaux in more detail, and Group 2 recommended software to arrange images. Some group members and Prof. Anderl also put forward some common issues for everyone to discuss.

Figure 8 Some participants attending the second all-group meeting. Screenshot by Christoph Anderl. Republished with permission.

Figure 8 Some participants attending the second all-group meeting. Screenshot by Christoph Anderl. Republished with permission.

Specialist sessions and all-group meetings provided opportunities to solve problems and improve the fieldwork in real-time. Therefore, all groups complete their tasks on time. In the last all-group meeting, Prof. Anderl encouraged participants to actively join such programs in the future and raised expectations for real fieldwork in East Asia in 2023.

The “Image – Text – Reality in Buddhism: Interrelation & Internegation” workshop and the virtual fieldwork are examples of large-scale international collaboration during the pandemic. The participants would like to thank Prof. Anderl and Dr. Lukicheva for organizing the workshop and the fieldwork, all scholars for sharing heuristic ideas and methodology, Vicky Baker from the University of British Columbia for administrating the workshop, and FROGBEAR for funding this series of informative training programs.

Author Bio;

Longyu Zhang is a Master student in Oriental Language and Culture at Ghent University. Her research interests lie in Chinese linguistics and Buddhist scriptures translated into Chinese. Her dissertation focuses on the methods Yijing 義淨 (635 –713) used to translate proper names in Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya Saṃghabheda-vastu.

Click here for the original posting