“Did women produce Buddhist texts in Medieval China? And does it matter if they did?” Lecture by Dr. Stephanie Balkwill

By Sarah Fink

Posted on

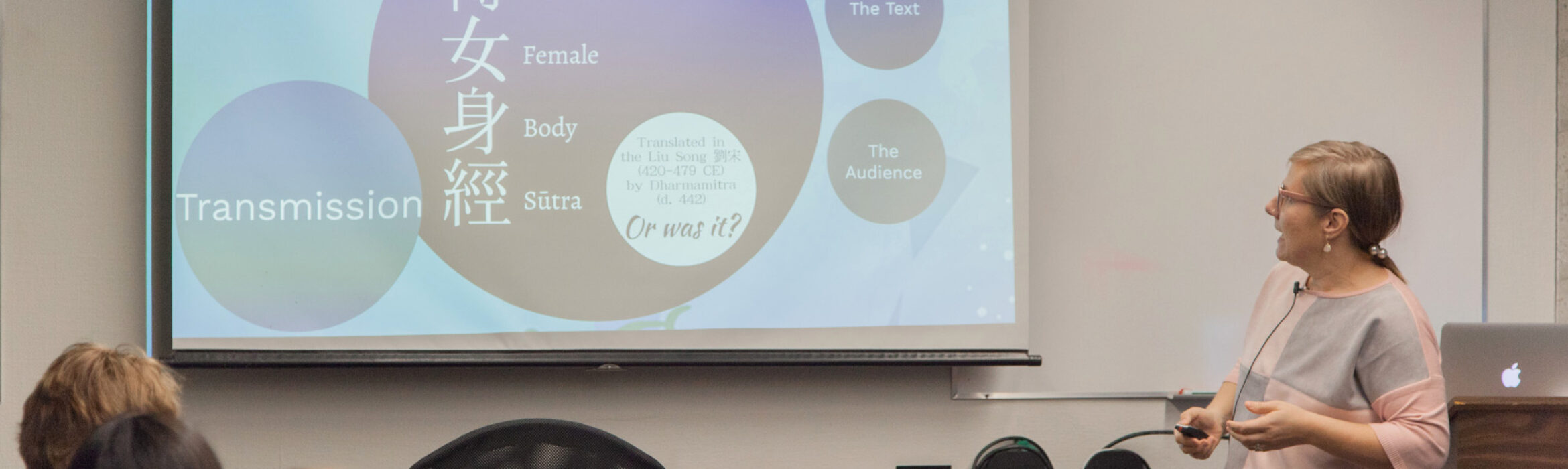

Photo courtesy of Carol Lee (UBC Frogbear)

On January 30, 2020, Dr. Stephanie Balkwill gave a lecture at the University of British Columbia titled, “Did Women Produce Buddhist Texts in Medieval China? And does it matter if they did?”. Dr. Balkwill is an Assistant Professor of Religion and Culture and East Asian Languages and Culture at the University of Winnipeg. She works on the fourth to sixth centuries in China and centers her research on the social, literary, and political lives of Buddhist women. For this lecture, Dr. Balkwill focused on a topic she recently became interested in while conducting research for another project: the impact that women, especially court women, had on the production of Buddhist texts during the fourth to sixth century in China.

Dr. Balkwill opened her lecture with a brief historical “window” into the fourth to sixth century China. This particular period was a time of major textual involvement, not just from translators but from a variety of social factors as well. She then focused on the role that women played in the production and dissemination of Buddhist texts, an aspect of textual involvement that is often not mentioned. She also demonstrated the notable presence of women and their impact on Buddhism at that time.

The most renowned example of women’s involvement in textual production is the powerful female ruler in medieval China, Wu Zetian, who ruled from 690 to 705 CE. She is an enigmatic, good example of text production because she was the sponsor of the Great Cloud Sutra, which helped validate her as a ruler. Although she is often pointed to as a prime example of powerful Chinese women, Dr. Balkwill argues that she is in fact an inheritor of a tradition that began centuries before her. This led Dr. Balkwill into a discussion of two main Buddhist texts: The Sutra on Transforming the Female Form and the Sūtra of Queen Śrīmālā of the Lion’s Roar.

The Sutra on Transforming the Female Form was translated by Dharmamitra (d. 442 CE) during the Liu Song 劉宋dynasty (420–479 CE). This sutra acts as the master text in explaining why it is beneficial to change your body (from female to male) on the Buddha path. This text presents two stories, but with only one ending: eventual sex transformation for the eminent woman. The first story is a prototypical “baby in the womb” story, as Balkwill described it: in a large gathering for the Buddha there is a pregnant Buddhist woman. The special child inside of her womb, a female, is noticed by the Buddha and eventually undergoes a sex transformation to fulfill the path of the Buddha. In the second story, there is a female protagonist who continually asks various penetrating questions. This character ultimately undergoes a miraculous sex change to prove her worthiness as a Buddhist practitioner. In both of these stories, the miraculous sex changes parallel the characters’ change in status as well and imply that there is a connection between altering your physical form to become male and achieving higher Buddhahood. Dr. Balkwill pointed out that although there are many texts related to the Sutra on Transforming the Female Form, few related texts remain existent today.

So, Dr. Balkwill asked, why become a man? There are different explanations according to various Buddhist text, but the most commonly cited reason is that the female body is karmically inferior. However, the Sutra on Transforming the Female Form the Buddha offers a “strikingly new” explanation on why to become a man. It strays away from the typical physical explanation and instead focuses on social gender. Dr. Balkwill then quoted from her own translation of this text:

When asked specifically why… [the Buddha] says, “the female body is like that of a maid servant and cannot obtain self-sovereignty… she’s constantly troubled by sons, daughters, clothing, food, and drink and other necessities related to family matters.” And [the Buddha] also says that the legal system, or the dharma system, for women does not allow a woman to have her own freedom. She must constantly be at the side of someone else, receiving “drink, clothing, perfumes, all type of adornments, elephant and horse carts,” so she gets a lot of stuff. I think this is a shout out to the objectification of women or the sort of special treatment of women. “And this is why she must give rise to the thought of abhorring and getting rid of her female body.”

Dr. Balkwill also quoted the text, “The body of a woman is used by others and cannot achieve self-sovereignty. Her labours are many, pounding herbs, milling rice… these many types of suffering are immeasurable.” The implication here is that it is not necessarily true that the female form is karmically inferior but because the female form is perceived lower on the social hierarchy, women therefore face a greater amount of suffering. This is the first text where we see social gender being used as an explanation for why women have to undergo sex transformation to achieve Buddhahood. Dr. Balkwill posited that it was possible the audience of this text was women, and most likely elite women, who were looking for a better explanation for this pointedly sexist aspect of the Buddhist path.

“Yes,” Balkwill joked as she continued into her next part of the discussion, “even being a princess sucks.” She discussed how even though women in the imperial palace were considered privileged, they were still subject to others and lack self-sovereignty. Surprisingly, many court women from the Liu Song dynasty ended up becoming monastics after their Buddhist master passed away. However, female ordinations were not official and legally done before this time period because there was no translation of the formal legal code. It was under the patronage of the Liu Song court that the Dharma Vinaya was finally translated, and women could be ordained legally. It is likely that they pressured the court to make ordination possible for them and pushed for patronage of their own lineage. The first official legal ordination was done in 432 CE. This renewal of female ordination procedures indicates that women could not only read and knew the Vinaya, but also had significant influence.

The second important text Dr. Balkwill discussed was the Sūtra of Queen Śrīmālā of the Lion’s Roar (Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra). This text was translated into Chinese in 436 CE by Gunabhadra (394–468) and preached at the Liu Song court. The text featured a queen who teaches with the force of the Buddha. Its transmission into Northern China is highlighted by the important Dharma Master, Shi Sengzhi 釋僧芝 (d. 516). Dr. Balkwill showed a rubbing of the eulogy inscribed on Shi Sengzhi’s tomb in exemplifying the unique power held by this nun. Sengzhi was the superintendent of bhiksunis and eminent for her ability to recite sutras, including the Śrīmālā Sūtra. The record of her remarkable ability to chant this sutra on her entombed biography and eulogy is the earliest dated mention in epigraphy.

Shi Sengzhi was ordained in 458 and brought to the Northern Wei court by Empress Dowager Wenming in 477, and later became the superintendent of nuns in 500. It was evident that Sengzhi was a highly respected Buddhist practitioner, especially because she was not of a royal or elite family and had no previous ties to the court. Her abilities to chant sutras brought her fame and she eventually held enough power in court that she not only worked as a private teacher to the emperor, but also was able to appoint her own niece to the court in 515, who later became Empress Dowager Ling (d. 528).

Despite the information we do know about Sengzhi, there remains a period of twenty years from about 458 to 477—the period between when she was ordained and when she was brought to the Northern Wei court—where Sengzhi is hard to place. Dr. Balkwill connected this strange lapse in information to the ordination and nun activity going on in the Liu Song dynasty and suggested the possibility that Sengzhi was learning the Śrīmālā Sūtra in the south during this time. This would present an example of nuns going to the south for Buddhist teachings and ordination and provide further information about the activities of Buddhist women during this time period.

After positing this information about Sengzhi, Dr. Balkwill focused in on the role of women as textual producers. She asked, “What were Buddhist women doing at the court of the Liu Song or with its sponsorship?” Dr. Balkwill discussed five ways where women might have been able to exert influence over Buddhist textual production. First, by becoming nuns, translators were forced to translate the texts needed for ordination. Second, women were influencing textual translation by being a critical mass and forcing translators to focus on texts they wanted translated. There were women eager to have texts relevant to them which affected which texts were being translated at the time. Third, by training their elite, these women were involved in developing their Buddhist careers and creating an “elite Buddhist womanhood.” Fourth, by reading, memorizing, and chanting sutras, they created a space for particular texts to have importance. Fifth, by being an audience for textual innovation, they were able to influence new texts that were being written at the time.

Dr. Balkwill concluded this talk by broadening the topic and discussing why studying the involvement of women matters. For Sengzhi, this matter because her relationship to Buddhist texts is what made her famous and why we know who she is today. She did not come from an elite family, but Buddhism gave her an opportunity to have influence and fame. Dr. Balkwill asserts, “The very fact that we are talking about her today is what matters.”

For Buddhism, this study matters because it shows new ways to do research on Buddhism. The Liu Song period is often ignored in preference for the Tang dynasty and beyond, yet it is important because of the high level of Buddhist textual development. By examining the many women in the court, we can see how they shared space with Buddhism, and how their contact with monastics influenced the way Buddhist texts were produced. This role of court women was not seen in later periods when textual production became more restricted to male monastics. It shows the way different people have related to Buddhism and evolved over time.

In terms of women’s history, this study demonstrated that women had more agency, movement and literacy than they were credited for. Dr. Balkwill joked, “It would be silly to question whether they could read.” However, it is more difficult to determine the mobility of women during this time. While there is not ample evidence to show that women moved around a lot during this time, there is also no sufficient refuting evidence that they did not. These questions are important to revisit and suggest that women had more agency, social mobility and social fluidity than we think.

Lastly, Dr. Balkwill wrapped up her talk by discussing why this study matters for the history of religions. Methodologically, there was not as much emphasis on institution typically. This study highlights the ways Buddhism effected the lives of women “in very concrete ways,” and in some ways even bettered their lives. It gave them social opportunity, education, and status outside of the family unit. This study allowed us to appreciate that “religious institutions are deeply important to the ways in which religion spreads,” for it was not just about texts and ideas, but also about what people were doing and how they related to big centers of power.

[Report originally posted on CJBS News Blog April 8, 2020. To see the original post, please click here.]