Abigail MacBain

University of Edinburgh

June 11, 2023

The first half of the two-year Enriched Reading Practices cluster met from June 25–29, 2022. It was led by Dr. Bryan Lowe of Princeton University and Dr. Lori Meeks of University of Southern California, both of whom are specialists in premodern Japanese religion. While initially designed to be held in-person in Japan, the ongoing COVID situation necessitated shifting this year’s event to an online forum, with both lectures and workshops scheduled to accommodate Japanese as well as East and West Coast North American time zones. This first half highlighted materials dating to the eighth century, with next year’s session set to feature items from Japan’s early modern period.

From left, Dr. Lori Meeks (University of Southern California) and Dr. Bryan Lowe (Princeton University)

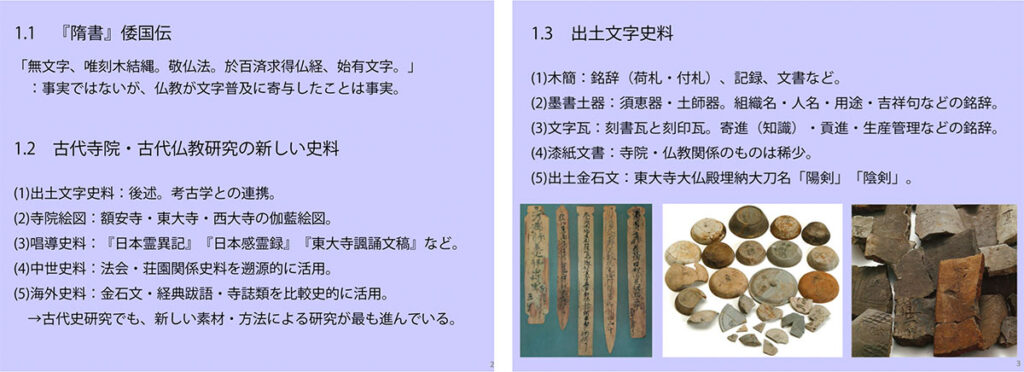

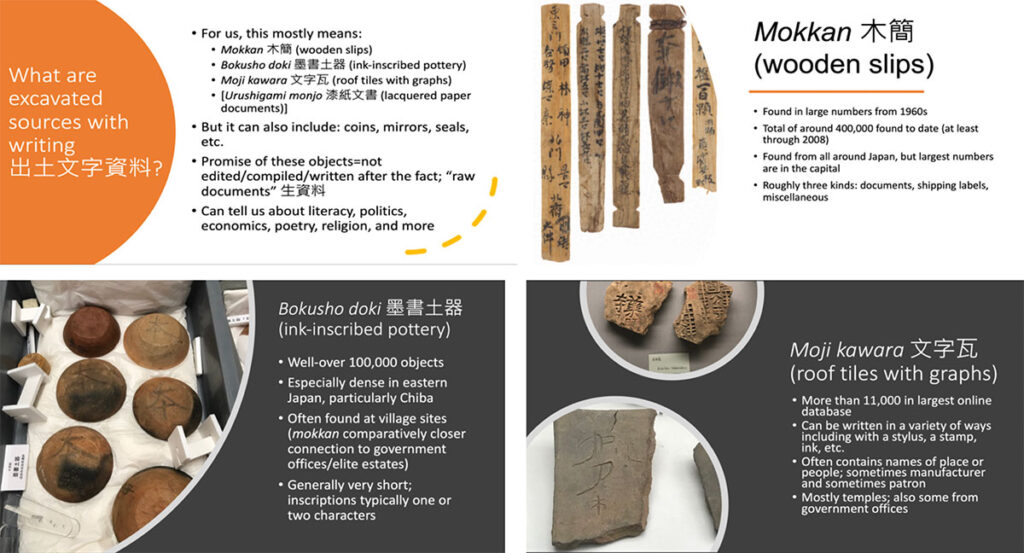

This year’s four-day online forum focused on how items from archaeological excavations that contain writing can be used in academic research, specifically on Japanese Buddhism. Collectively these sources are referred to as shutsudo moji shiryō (出土文字史料), or “excavated sources with writing”. These items are categorized as:

- Mokkan 木簡: narrow wooden tablets with writing

- Bokusho doki 墨書土器: ink-inscribed pottery

- Moji gawara 文字瓦: roof tiles with inscriptions

- Urushigami monjo 漆紙文書: lacquer-infused paper

There is also a broader fifth category of epigraphic materials made of metal and stone, or kinseki bun (金石文), which includes engraved tools and everyday items such as coins, swords, and seals. The written contents of the excavated items with writing vary widely, ranging from shipping labels and students’ writing practice, to doodles and cartoon-like images, to patrons’ names and the item’s intended purpose. The cluster’s sessions focused on objects from the first three categories.

While these excavated sources with writing constitute some of the earliest extant examples of writing in Japan, paradoxically they are among the newest sources informing scholarly understandings of premodern Japanese history and culture. These materials are particularly underutilized in Western scholarship, partially due to their fragmentary and highly varied nature, as well as difficulty in accessing both the original objects and the archaeological reports within which basic information is published. In order to encourage junior scholars to see excavated materials with writing as resources, the talks featured four established Japanese scholars who each use archaeological findings in their research. There was also a hands-on GIS mapping component led by Bryan Lowe, who additionally lectured on the excavated materials with writing. In this way, participants engaged with excavated materials from both the qualitative angle of their materiality and contents as well as their data-based quantitative contributions.

Top row, from left: Kondō Yasushi (Sakai City; Kansai and Kinki Universities) and Yoshikawa Shinji (Kyoto University)

Bottom row, from left: Hishida Tetsuo (Kyoto Prefectural University) and Baba Hajime (Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties). Screenshots by Abigail MacBain. Republished with permission.

Kondō Yasushi 近藤康司先生: Ōnodera and Inscribed Rooftiles 大野寺と文字瓦

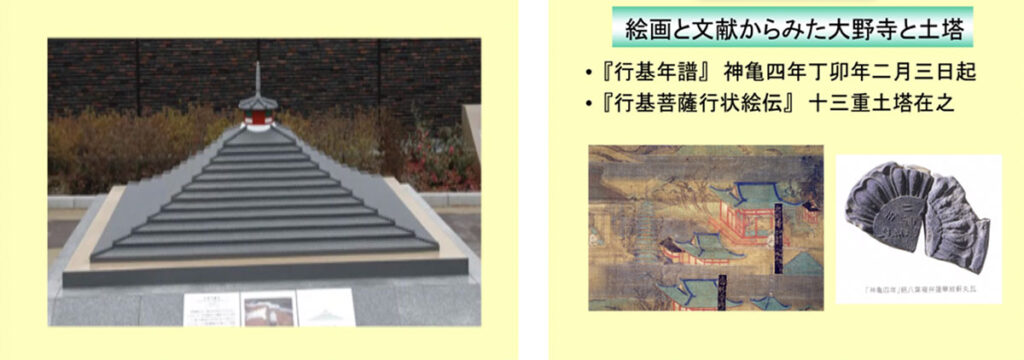

The first speaker was Professor Kondō Yasushi, the curator of cultural properties for Sakai City as well as a lecturer at both Kansai and Kinki Universities. Professor Kondō presented on inscribed roof tiles used in the unique eighth-century “earthen pagoda”, or Dotō (土塔), located at Ōnodera Temple in modern-day Sakai City. Unlike standard Japanese pagodas featuring a central column and multi-layered roofs, Dotō’s shape more closely resembled a step pyramid and was made of compacted earth covered with clay tiles. In examining where the tiles interrupted bands of dirt, archaeologists have determined that the pagoda contained thirteen levels, a point that corresponds with a reference from the Gyōki bosatsu gyōjō eden 行基菩薩行状絵伝 relating to the pagoda. Similarly, a decorative end piece of roofing tile bearing the date equivalent to 727 is in agreement with the Gyōki nenpu’s 行基年譜 mention of the temple’s construction. Considering that both texts date to later periods and contain suspect material, in this case the archaeological evidence supports the written records.

Left: a model of the Dotō pagoda’s original shape. Right: primary source references that correspond with archaeological finds. Slides courtesy of Kondō Yasushi. Reprinted with permission.

More than one thousand of Dotō’s roof tiles are moji gawara, typically with the name of individuals who likely contributed to the project. In a manner similar to how a modern-day institution might prominently display an engraved list of donors, these tiles indicate those who directly contributed to the construction of Dotō and, presumably, Ōnodera itself. Kondō pointed out that a great deal of information can also be gleaned from what types of tiles had names on them, which sides of the tile bore the names, and the manner in which these names were written into the tile, especially in terms of handwriting, pressure, and implements.

Kondō divided these name moji gawara into four categories:

- Betsumei de betsuhitsu 別名で別筆: different names in different hands, potentially written by the named individuals themselves.

- Dōmei de dōhitsu 同名で同筆: the same name in the same hand, indicating a number of repeated names on numerous tiles, perhaps all of which were written by the same person.

- Dōmei de betsuhitsu 同名で別筆: the same name in different hands, suggesting perhaps two people wrote the name separately.

- Betsumei de dōhitsu 別名で同筆: different names in the same hand, in this case reflecting names that closely resemble each other, such as by having the same surname. The names were potentially written by the same person, and there may have been a connection between the writer and two related individuals.

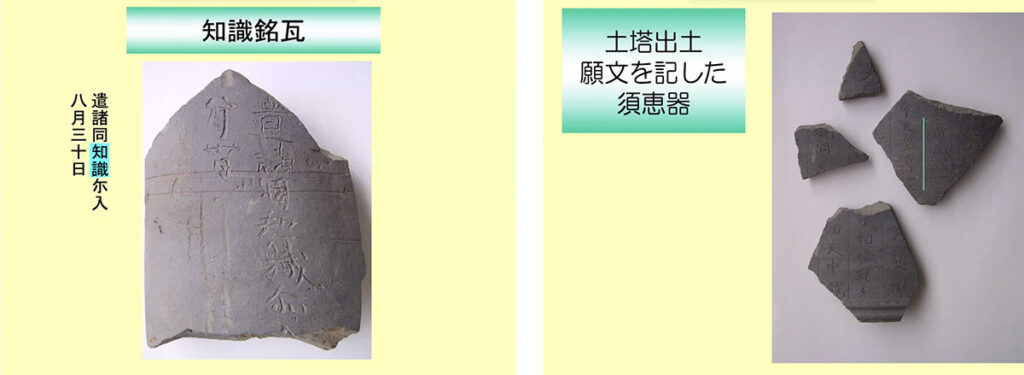

The moji gawara bearing individuals’ names provide particularly valuable insight into family relations and movement of people otherwise left out from historical records. For example, Kondō pointed to several examples with identifiably feminine names. This demonstrates that there were multiple women involved with Buddhist fellowship groups, or chishiki 知識, that contributed to Buddhism’s spread during this time. Names from the Haji 土師 kinship group also appear on moji gawara, suggesting a connection between this packed-earth pagoda and a family that in previous periods was known to have built giant earthen graves called kofun 古墳. Some names also correspond with known followers of the famed eighth-century engineering monk Gyōki 行基. The previously mentioned texts credit Ōnodera and Dotō’s construction to Gyōki, and the presence of these followers’ names supports those claims.

In addition to the names, Kondō argued for the importance of looking at the materiality of the roof tiles themselves. This included awareness of the different shapes and positions of the tiles, how they were formed, and the processes involved with their production. The fact that we see multiple handwriting styles reflected in the inscribed clay is in and of itself indicative of who had access to the tiles while they were still in the manufacturing process. Unlike bokusho doki, where characters were written in ink upon finished pottery, the Dotō’s moji gawara were inscribed while the clay was still wet. As such, the writers would have needed to be at the worksite during the short stage between the tiles’ being removed from their molds and their being fired in the kiln.

Kondō also demonstrated an example of a moji gawara mentioning a chishiki group seemingly made up of Gyōki’s followers, including monks, nuns, and laypeople who had a connection to this temple. Similarly, he showed images of inscribed sueki 須恵器 pottery including written prayers, or ganmon 願文, that while not technically moji gawara, still reflect donors’ intensions and connections to the temple. Significantly, this ganmon example was issued on behalf of the emperor. As such, inasmuch as the excavated materials with writing can give a name or voice to those left out of the official histories, they also suggest that class, political, and gender lines were not necessarily impermeable barriers. Especially in a temple context like Ōnodera, there were opportunities for the names of varying classes, if not the individuals themselves, to intermingle.

Left: a tile mentioning a chishiki group. Right: tile fragments expressing a ganmon. Slides courtesy of Kondō Yasushi. Reprinted with permission.

Yoshikawa Shinji 吉川真司先生: Keynote Address: Ancient Japanese Buddhism as Seen from Excavated Materials with Writing 基調講演:出土文字史料からみた日本古代仏教

Yoshikawa Shinji, a professor and specialist on early Japanese history at Kyōto University, delivered the keynote address on the second day of talks. In addition to providing a detailed overview of the five categories of excavated sources with writing, Professor Yoshikawa focused on how these items can contribute to greater understandings of daily life at early Japanese religious sites, especially Buddhist temples. While the relationship between early Japanese bureaucracy and excavated sources with writing has been well explored, especially in the case of mokkan, that has not necessarily been the case with religious sites. This is partially due to the fact that the items’ written contents do not necessarily reflect religious belief or practice, or they may be piecemeal at best. However, when considering the context within which they were found and in relation to other written source materials, excavated items are a valuable component in the construction of Japan’s religious history.

In terms of their role in contemporary academic research, the excavated sources with writing represent just one category of newer historical sources that have been increasingly used by scholars of early Japanese religious history within the past thirty or so years. In the case of the excavated sources with writing, historians have been increasingly using these materials since approximately the 1960’s. Yoshikawa also pointed to four other types of sources that scholars of early Japanese history have increasingly used in recent years:

- Drawings of temple precincts, ji-in ezu 寺院絵図, including maps that depicted temple layouts and how buildings were used.

- Shōdō shiryō 唱導史料, referring to Buddhist preaching materials including temple narratives and liturgical notes.

- Texts from the medieval period, chūsei shiryō 中世史料, which may provide supplementary information on temples whose founding may date back to earlier periods. These sources include materials related to religious rituals or temple estates known as shōen 荘園.

- Overseas materials, especially those produced in China and Korea. These include epigraphic metal and stone items, sūtras, and temple records that can be studied comparatively to consider what the situation may have been like in Japan.

Left: a passage from the Sui shu and a list of newer sources increasingly used by Japanese historians. Right: categories of excavated sources with writing. Slides courtesy of Yoshikawa Shinji. Reprinted with permission.

A core theme in Yoshikawa’s talk was the relationship between the excavated sources with writing and Japan’s history with writing itself. Despite bearing words and characters, these objects are not literary texts. They are a distinct category of source material with unique advantages and disadvantages. As such, the manner in which they are engaged must be distinct from literary texts such as court histories or temple narratives. However, Yoshikawa noted that they are still part of the history of writing as well as Buddhism’s promulgation in Japan. To emphasize this point, Yoshikawa began his talk about the excavated sources with writing with a quote from the seventh-century Chinese history of the Sui Dynasty, the Sui shu 隋書. The passage is translated here as: “[In Japan] there was no written script, only carved wood and knotted cords. [Japan] venerated the Dharma and sought Buddhist teachings from [the Korean kingdom of] Paekche. [At that point Japan] began to have a written script.” 無文字、唯刻木結縄。敬仏法。於百済求得仏教、始有文字 。While writing in Japan predated Buddhism’s official introduction, this passage nonetheless demonstrates a perceived link between writing and Buddhism’s development. It is with this underlying understanding of the link between writing and Buddhism that we can better consider the context within which inscribed materials were found at religious sites.

In looking at the excavated sources with writing, Yoshikawa emphasized that these objects should not be considered in isolation. When evaluating both object and content, it is necessary to ask questions such as: in what sort of location was it found? What kind of item or material is it? What other items were found alongside it? What can be discerned from the writing beyond just its contents? With these base questions established, Yoshikawa proceeded to present examples of mokkan, bokusho doki, and moji gawara that had been found at temples and shrines.

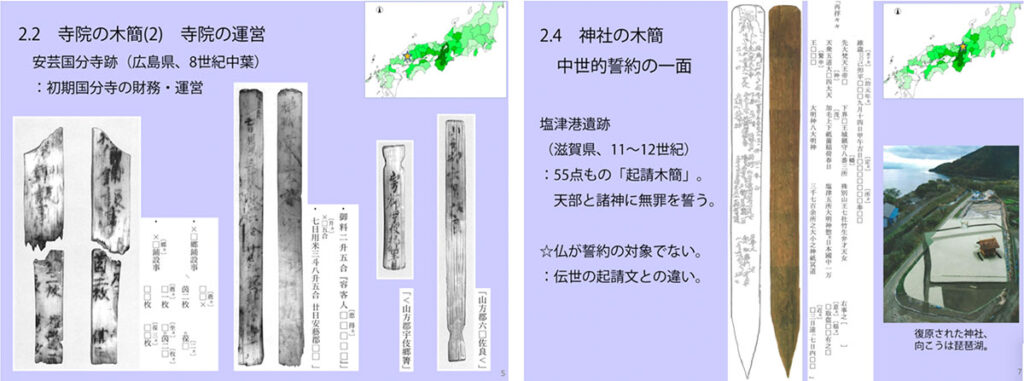

Starting with mokkan, Yoshikawa presented examples from Sairyūji 西隆寺, a convent in Nara; the state protection temple, or kokubunji 国分寺, from Aki 安芸 province in modern-day Hiroshima prefecture; and Asukadera 飛鳥寺 in the seventh-century capital city of Asuka. Several of the mokkan found at these temples related to non-religious activities that were essential to the temples’ upkeep and management, including matters such as construction, donations, and finances. There were also mokkan mentioning religious services, items necessary for carrying out ceremonies, and monks’ names. Mokkan listing other temples demonstrate the networks that existed among religious institutions at this time. Even in fragmentary format and without added context, these wooden slips provide hints as to these Buddhist institutions’ activities, managements, and connections.

Left: mokkan examples from Aki province, dating to the mid-eighth century. Right: mokkan from a shrine in Shiotsukō, dating to the eleventh-twelfth century. Slides courtesy of Yoshikawa Shinji. Reprinted with permission.

In addition to these temple-based mokkan, Yoshikawa also introduced a few found at shrines. The first example was notable in that its eleventh–twelfth century date placed it much later from the seventh–eighth century objects presented previously. Additionally, compared with the larger temple sites in more populated areas, this mokkan was found at an archaeological site at a smaller and more rural shrine located in Shiotsukō 塩津港 on the northern shores of Lake Biwa. As such, it provides valuable insight into the local beliefs and customs of this area. Yoshikawa categorized this piece as a kishōmon mokkan 起請文木簡, meaning that it bore a vow to the gods. Notably, the kishōmon mokkan addressed not only Japanese kami but also gods from the Buddhist pantheon in avowing the author’s innocence. It demonstrates the degree to which Shinto-Buddhist syncretic belief influenced religious practice in this area at this time.

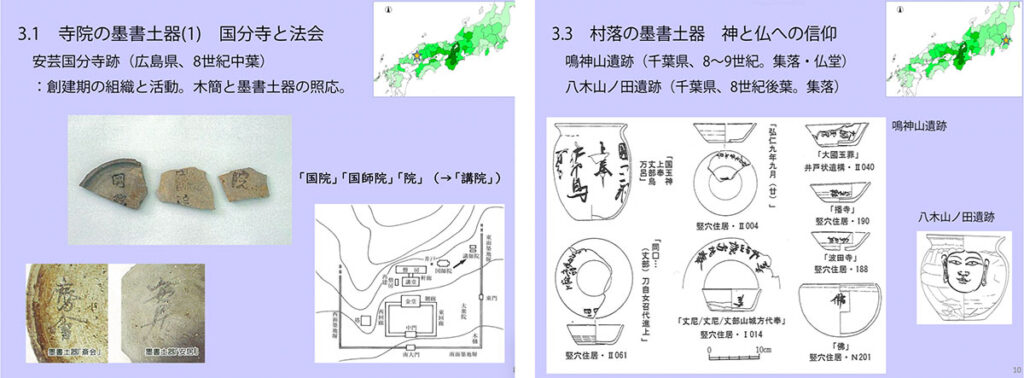

Yoshikawa next switched to looking at pottery sherds with writing on them, bokusho doki. He provided examples from the previously mentioned Aki kokubunji, from Kiyomizudera Temple 浄水寺 in modern-day Ishikawa Prefecture, and from various archaeological sites in Narukamiyama 鳴神山 as well as Yagiyama no ta 八木山ノ田 in modern-day Chiba. Collectively, the pieces range from the eighth to the eleventh century. Yoshikawa noted that the writing on the bokusho doki often related to institutions’ organizations, people’s names, and the item’s intended use. These pieces corresponded with Yoshikawa’s overall argument that, by themselves, excavated sources with writing cannot reveal a great deal of usable material. Instead, their greatest value comes from looking at them in groupings. For example, an assortment of sherds bearing characters like kokushi-in 国師院, kokushi 国師, koku-in 国院, and in 院 on the grounds of the Aki kokubunji archaeological site identified the structure within which they were found as the temple’s lecture hall, or kō-in 講院. This was the residence for the kokushi 国師, who was in charge of the province’s Buddhist instruction and also presided over the temple’s bureaucratic and ceremonial functions. Examples from the Kiyomizudera site contained auspicious phrases or prayers, and items from the Chiba sites provide direct insight into Shinto-Buddhist syncretic worship from the eighth and ninth century. Even in fragmentary form, bokusho doki collectively provide insight into the beliefs, activities, and populations in and around religious sites.

Left: bokusho doki from the Aki kokubunji that helped identify the kō-in. Right: drawings of pieces from the Narukamiyama and Yagiyama no ta sites that reflect Shinto-Buddhist syncretic worship. Slides courtesy of Yoshikawa Shinji. Reprinted with permission.

Finally, Yoshikawa turned to examples of eighth-century moji gawara from the kokubunji in Musashi 武蔵 province in modern-day Tokyo ward as well as from the former temple sites Yamazaki haiji 山﨑廃寺 in Kyoto and Miya no Maehaiji 宮の前廃寺 in Hiroshima. These examples included roofing tiles where characters were stamped into the wet clay as well as those that were carved, and their contents include the names of regions as well as individuals. In one case, the tile manufacturing supervisor was listed. From Yamazaki haiji and Miya no Maehaiji, Yoshikawa pointed to indications of chishiki groups potentially connected with Gyōki as well as the names of several women, thereby building upon the previous day’s lecture. Some moji gawara also contained appeals on behalf of the donors’ parents.

Yoshikawa concluded by summarizing four main points to be aware of when working with excavated sources with writing:

- Consider the context and setting within which the items were found.

- Look at items as a group instead of each piece individually.

- View pieces directly, as publications and databases can contain mistakes.

- Use excavated materials in collaboration with other sources.

In summation, while excavated sources with writing are valuable materials, the fact that they bear text does not make them “texts” and therefore need to be worked with in a different manner.

Bryan Lowe ブライアン・ロウ: Introduction to excavated sources with writing, databases, and group project 出土文字資料、データベース、グループプロジェクトの紹介

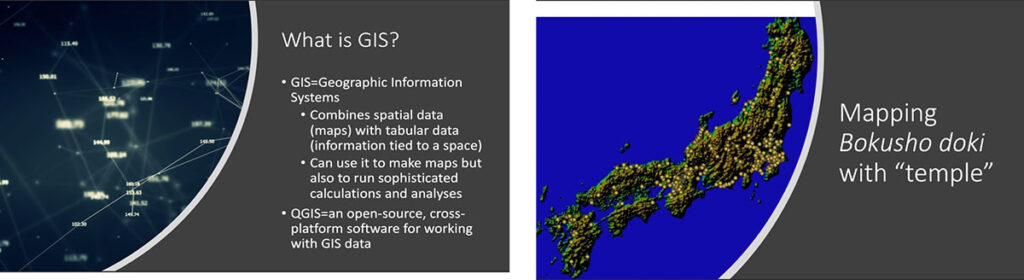

For his presentation, Princeton University professor and cluster leader Dr. Bryan Lowe combined an overview of the excavated materials with a hands-on activity on how to work with data from the archaeological digs in academic research. Compared to the more formal talks by the four Japanese presenters, Lowe referred to this as a “mini-lecture”, and he included a step-by-step demonstration of finding and using archaeological data in GIS mapping software.

In going over the categories of unearthed sources with writing, Lowe reiterated a point from Kondō’s lecture that these were “raw” and “unedited” materials, although with the caveat that this did not mean that the items were devoid of ideological or literary purposes. Additionally, the presence of written characters in some of these objects did not necessarily equate to literacy, especially in the case of earlier finds. Nonetheless, these items do have certain advantages compared with texts that were often written or compiled well after the periods depicted therein. For example, the names of women and manufacturers were more likely to be included in these excavated sources. Additionally, the items’ varied natures means that they can often provide supplementary information related to a variety of topics, including the development of literature and literacy, political figures, taxation, marketplaces, and trade. Lowe listed several Western scholars who use excavated materials in their work, including David Lurie, Joan Piggott, Wayne Farris, Marjorie Burge, and Joshua Frydman.

Slides explaining the categories of excavated sources with writing and providing details on the three categories examined here: mokkan, bokusho doki, and moji kawara. Slides courtesy of Bryan Lowe. Reprinted with permission.

Lowe then broke down the three major types of excavated materials with writing considered in this series of talks. In particular, he gave a broad overview of their estimated numbers, contents, locations, and contributions to Buddhist studies. For numbers of items, the most recent estimate Lowe found for mokkan was from 2008, which tallied at around 400,000. There may well be more by now. For bokusho doki, the numbers are complicated by the fact that many have yet to be catalogued or are in small municipal or township museums that are difficult to access. At the very least, there were over 100,000 in an online database, and it is possible that they may actually outnumber mokkan. The moji gawara similarly lack a concrete number, but there are certainly far fewer than the other two. In one database, Lowe found around 11,000 examples. Nonetheless, all three are numerically rich sources.

The writing on the excavated sources also can vary depending upon their type. Mokkan are divided into three categories based upon their contents:

- Documents, such as tracking laborers’ working hours;

- Shipping labels, including items sent for tax purposes; and

- Miscellaneous, which accounts for everything from calligraphy and poetry to doodles.

The passages on mokkan are fairly short, even more so if they are fragmented. The writing on the bokusho doki is even more limited, often just one or two characters. These characters are commonly related to their intended use, an aspiration or appeal, a location, or a person’s name. The contents of the moji gawara have already been discussed at length in previous talks, but one notable aspect is that they regularly identify locations. Lowe pointed to an example from a kokubunji where every district within the province was represented by either a bokusho doki or a moji gawara. This suggests that the districts were making offerings to their local kokubunji and also hints at regional networks.

Another important consideration with the excavated sources with writing is the locations within which they are customarily found. Mokkan most commonly appear around the capital region or in close proximity to bureaucratic centers and aristocratic houses. As such, Lowe noted that mokkan are not necessarily the best sources for studying Japanese Buddhism or provincial religious practice. Roof tiles, however, are very valuable materials for this purpose, as many are from temple sites or occasionally government offices. However, as tiles were restricted to the most important temples and official buildings, these provide little insight into those peoples and places unconnected with the Japanese government. By comparison, bokusho doki are commonly found throughout rural areas, in part because of the simplicity of manufacturing basic earthenware. Lowe showed a picture of bowls from Chiba-prefecture bearing a character variant for tatematsuru 奉, meaning “to present”. The bowls were likely used for offerings at the small village temple where they were found. Compared to mokkan or kawara, bokusho doki can provide direct insight into life and rituals of sites less tied to central control and official affiliation with the state.

Lowe then switched to discussing databases of excavated sources that can be used for digital humanities projects, such as plotting each data point onto a map. He identified four websites in particular:

- Wooden Tablet Database: https://mokkanko.nabunken.go.jp/ja/

- Bokusho doki and moji kawara database: https://bokusho-db.mind.meiji.ac.jp

- Multi-database Search System for Historical Chinese Characters: https://mojiportal.nabunken.go.jp/en/

- A list of resources on the website for the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties (Nabunken): https://www.nabunken.go.jp/publication/

These databases provide a multitude of search options, allowing for very focused engagement with the excavated materials.

Slides introducing the GIS mapping component of the workshop. Slides courtesy of Bryan Lowe. Reprinted with permission.

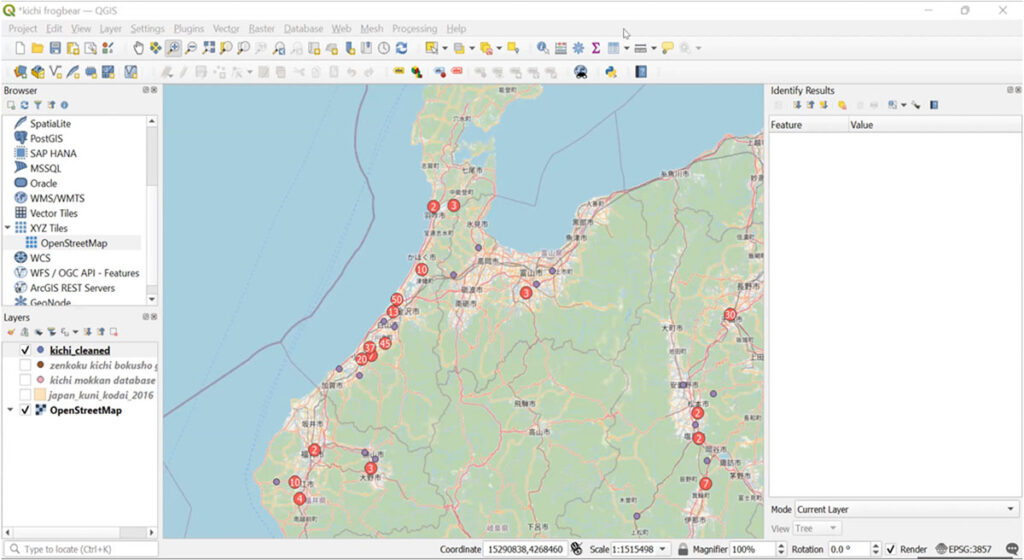

Upon downloading the relevant data sets, Lowe led participants through the process of loading them into QGIS, an open-source mapping program that is compatible with Apple and PC computers. As an additional option, Lowe showed participants how to overlay old Japanese maps from Imazu Katsunori’s website to see how the data points appear with historical borderlines. In the two follow-up sessions, Lowe split participants into two teams and allowed them to develop independent projects that required finding and downloading relevant data sets, uploading them into QGIS, and presenting what they were and were not able to uncover through the software. The first group searched for sites that had objects with the character for kichi 吉, meaning “luck” or “fortune”, from around Japan. The second group selected a sample of dig sites based at kokubunji and their convent counterparts, kokubunniji 国分尼寺, and used a QGIS measuring tool to see if distances between the temple pairs were consistent throughout the provinces.

Top: Using QGIS to plot sites of bokusho doki bearing the character kichi.

Bottom: Using QGIS to measure the distance between kokubunji and kokubunniji sites.

Screenshots taken by Abigail MacBain. Reprinted with permission.

Through the mapping exercise, participants were introduced to another method of interacting with the excavated sources with writing outside of their direct content or materiality. The plot points demonstrated the range and connections among the objects and their locations on a macroscopic level. With deeper refining and additional work, these projects could be used to better understand regional mobility as well as geographical, cultural, and social interconnections. Additionally, these workshop sessions provided opportunities for participants to get to know one another and learn more about each others’ research interests.

Another intended goal of the exercise was to give participants direct experience in the difficulties of working with data sets. One issue is the overrepresentation of certain sites. Lowe reiterated a point from Yoshikawa’s talk concerning the bevy of excavated materials found in Chiba Prefecture, just outside of Tokyo. While it is possible that there are historical reasons for numerous inscribed objects being created in or sent to this area, the large number of recovered items must be viewed through the lens of urban sprawl and development throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century. Another issue is limitations to the websites themselves. The primary website used for the mapping exercise did not work for half of the participants. Even when data sets were available, they typically needed to be cleaned, and variations in recording methods complicated the information. Corrupted data, input errors, conversion mistakes, and user inexperience also led to problems that were nonetheless insightful.

Hishida Tetsuo 菱田哲郎先生: Inscribed Pottery and Kamiodera 墨書土器と神雄寺

As with Prof. Kondō and Prof. Baba’s sessions, this lecture replaced what was intended to have been a hands-on aspect to the cluster. Originally, participants would have gone to the artifact processing center in Kizugawa 木津川 City in Kyoto prefecture in order to view examples of bokusho doki from Kamiodera Temple directly. Instead, Hishida Tetsuo, a professor in the department of literature at Kyoto Prefectural University, brought participants to the facility over Zoom, where they could at least see the materials being handled. Professor Hishida was assisted by his former student, Ōtsubo Shūichirō 大坪州 一 郎, who currently works for the cultural properties division in Kizugawa City. The office was outfitted with a complex camera setup that allowed for detailed close-ups of the objects, thereby giving participants the next best thing to direct exposure.

Image of Hishida Tetsuo and Ōtsubo Shūichirō at the artifact processing center in Kizugawa City. Screenshot by Abigail MacBain. Reprinted with permission.

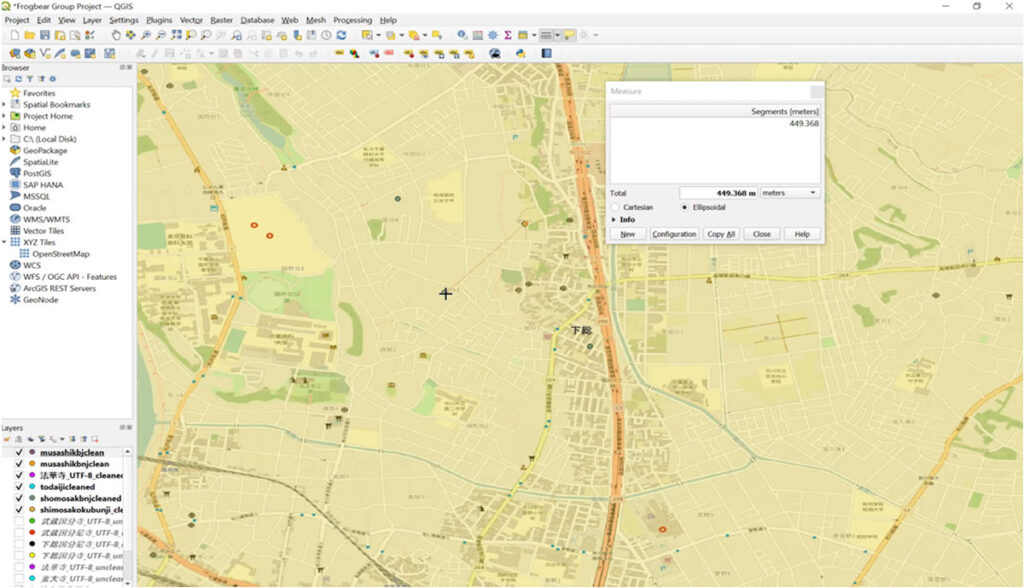

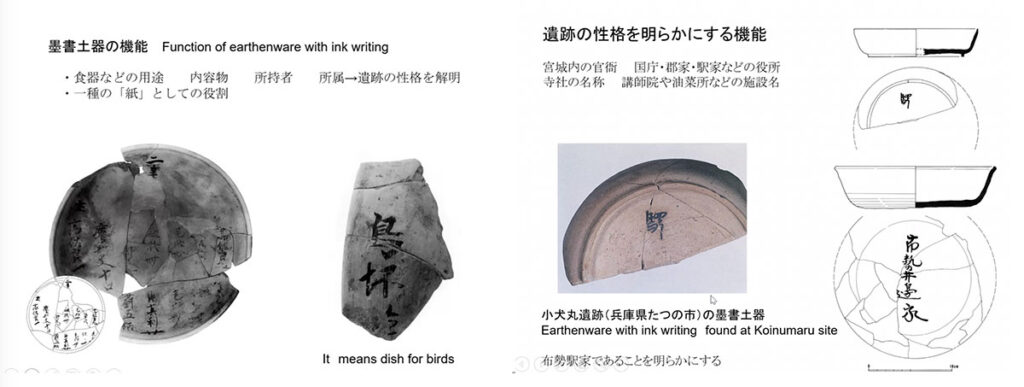

The focus of this talk was on bokusho doki and what their writing reveals about these pieces’ purposes and uses. As mentioned in previous talks, the characters on bokusho doki tend to be limited to only a few characters, quite often a label denoting the item’s purpose, a location, or a person’s name. However, the physicality of the pottery can also reveal information about how it was used or give insight into local religious practices. Hishida provided several examples of objects being used in relation to water-based rituals that may have predated the establishment of a Buddhist temple there. As such, they reflect the combinatory religious practices at play in the area.

Hishida began with an overview of bokusho doki and their potential uses. In one example, a pottery fragment had the words “bird dish”, or tori tsuki 鳥坏, therefore indicating that it was intended for feeding birds. Another example from the Koinumaru 小犬丸 site in Fuse, Hyogo Prefecture had a character for “station”, or umaya 駅, on its underside. As a result, the dig site could then be identified as an early roadside official rest station, where messengers could change horses and important guests were entertained. Inscribed pottery can also be used to identify the location of regional offices or pinpoint which buildings in a temple complex were used for what purpose. Similar to the kokushi example from Yoshikawa’s lecture, Hishida showed an image of a pottery fragment from the Kazusa 上総 kokubunji in Chiba that contained characters for the lecture hall. Another piece identified the site for processing oil, an important component in Buddhist ceremonies.

Examples of bokusho doki that indicate purpose or location. On the left is an example of a dish for feeding birds, and on the right is a fragment with the word for “station.” Slides courtesy of Hishida Tetsuo. Reprinted with permission.

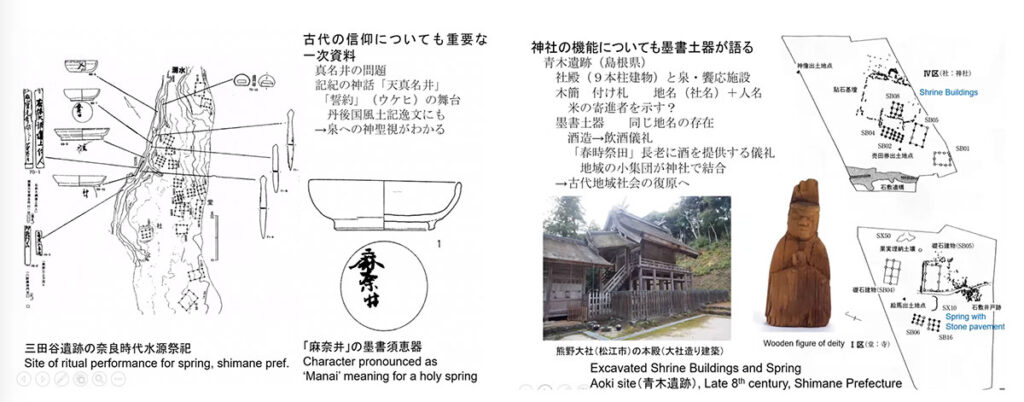

Next, Hishida discussed what bokusho doki can tell us about regional religious practices. One notable example was the Santadani 三田谷 site in Shimane prefecture, where there are building remains and ritual implements in proximity to natural springs. In one of the locations, there was a bowl bearing the characters for manai 麻奈井, referring to a well. The same term appears in a Japanese myth depicting a vow exchange between the gods Amaterasu and Susanoo. Hishida also looked at archaeological evidence of a spring-based ritual practice at two locations in Mie Prefecture, including at Amaterasu’s Inner Shrine at Ise 伊勢, and at the Aoki 青木 site in Shimane Prefecture. In this latter case, there were post holes suggesting a shrine-like structure as well as mokkan, bokusho doki, and a wooden icon that all give insight into the religious practices of the area. Hishida suggested that there were indications of rice donations and sake manufacturing for ritual or entertainment purposes.

Slides indicating archaeological finds near water sites connected with religious practice. Slides courtesy of Hishida Tetsuo. Reprinted with permission.

The next site considered was Mirokuji 弥勒寺 Temple in Gifu Prefecture. This was the familial temple of the Mugetsu 身毛, which had been one of the more powerful kinship groups in the Asuka period’s court. The temple itself demonstrated the ties between religion and politics at this time, as the provincial government buildings flanked the temple’s eastern side. Additionally, among the bokusho doki are dishes inscribed with the characters “great temple”, ōdera 大寺, which could have either been an official designation or a reflection of local popular practice. Other examples include monks’ names and the character sonaeru 供, meaning “to serve”. Mirokuji also reflected local combinatory religious practice, as there were ritual instruments related to water-based worship located at a natural spring on the temple’s western side. In his presentation, Hishida portrayed these as overlapping spheres of politics, Buddhism, and local religious practice.

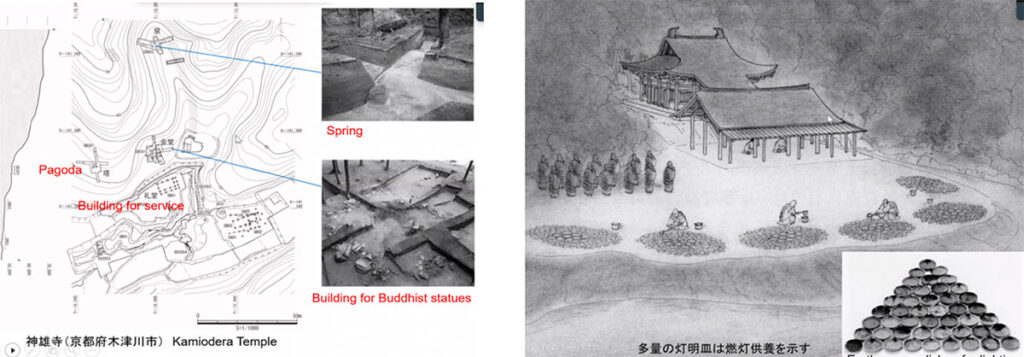

From here, Hishida transitioned to talking about Kamiodera Temple in Kizugawa City and several of the items found there. As with Mirokuji, Kamiodera was clearly a site of combinatory religious practice, as evidenced even in the fact that its name combined characters for Japanese gods, kami 神, and Buddhist temples, tera/dera 寺. As with the other sites, there was a natural spring in close proximity to the temple. This site also yielded a large number of excavated sources with writing that indicated the types of ceremonies and daily activities at the temple. For example, one potsherd had the term for purity, jō 浄, and another had the term for a Buddhist repentance ritual, keka 悔過.

Dig sites at Kamiodera, including a depiction of how tōmyōzara dishes were used for burning oil. Slides courtesy of Hishida Tetsuo. Reprinted with permission

Ōtsubo took the lead in demonstrating specific bokusho doki that had been found at Kamiodera. Of the excavated items, 113 have writing on them, and approximately half of those include the characters for or variants of the temple name Kamiodera. The regional name Baba Minami 馬場南 also appeared on several bokusho doki. In looking at the fragments themselves, variations were clear not only in characters, but also in the size, clarity, and color of ink. Of particular note were examples of shallow dishes known as tōmyōzara 灯明皿 that were used for Buddhist oil burning rituals. There were approximately 3,000 to 5,000 tōmyōzara found at Kamiodera. One example also had a faint drawing of a lotus flower on the bottom, making it a bokusho doki. Compared with tōmyōzara found in other locations, Ōtsubo noted that the ones at Kamiodera had very mild charring on the underside, suggesting that these had been only used once.

Examples of tōmyōzara found at Kamiodera displayed by Ōtsubo Shūichirō. The example on the left has a black mark at the top indicating it was exposed to a flame. The example on the right has a faint outline of a lotus flower, a drawing of which is shown next to it. Screenshots by Abigail MacBain. Reprinted with permission.

Of the pottery pieces that had the temple’s name written on them, they were largely items that had a serviceable function. These uses are apparent not only through the characters written on them but also sometimes by their physical appearance. The smoothness in one bowl suggested it had been rubbed back and forth multiple times with an ink stone. This was a valuable example of how directly interacting with excavated items can teach us something about their use that mere images or even merely looking at them cannot. The session ended with an appeal by Hishida for participants to come see and feel these objects for themselves.

Baba Hajime 馬場基先生: Mokkan and Buddhist History 木簡と仏教史

The final talk featured Baba Hajime, an archaeologist and scholar of early Japan, who is a specialist in relation to mokkan as well as the eighth-century capital at Heijō 平城. Professor Baba is the head of the History Section in the Department of Imperial Palace Sites Investigations for the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, commonly abbreviated as Nabunken. He is also involved with the National Institute for Cultural Heritage and has worked with the Institute of Ancient Cultural History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences as well as Academia Sinica in Taiwan. He also regularly appears in Japanese news segments regarding archaeological finds.

The first segment of the talk provided a brief overview of the Nabunken’s activities and Baba’s own excavation experience around the world. As a specialist in mokkan, Baba stated that all tablet specialists are friends, giving him contacts as far afield as Xi’an and Pompei. This sense of global interconnectedness permeated the lecture, which took into consideration the historical setting within which texts traveled and were used. The region within which a textual tradition developed and was exported to Japan influenced not only the content but also the writing surface and physical manner in which writing was conducted. More broadly, this textual mobility occurred within the larger sphere of Chinese influence, with East Asian Buddhist countries interacting with Buddhist texts not in Sanskrit, but rather through the filter of Chinese characters and their related culture.

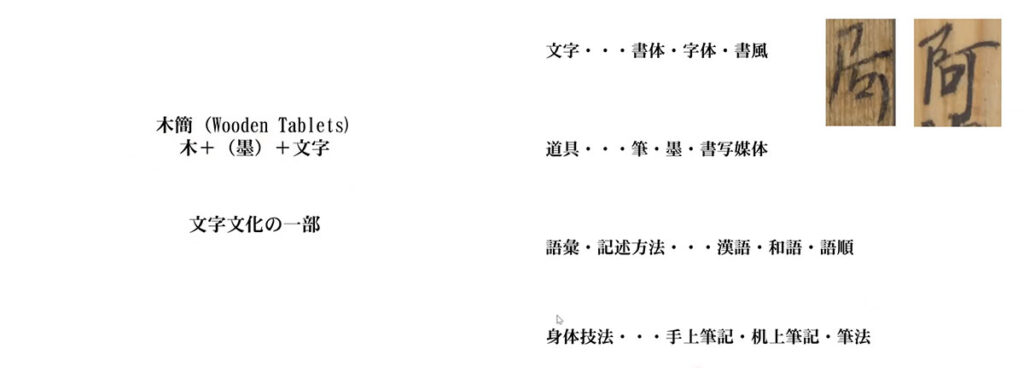

Baba introduced a simple formula for conceiving of mokkan: wood + ink + characters. Beyond mere content, Baba also encouraged looking at four notable things when considering these inscribed wooden slips:

- Characters, moji 文字: the font type (i.e., calligraphic vs. block style), the character shape, whether it was a character variant, and the handwriting style

- Implements, dōgu 道具: the type and manufacture of brush, ink, and writing surface, as well as transcription or copying media

- Vocabulary, goi 語彙, and the sentence style kijutsu hōhō 記述方法: presence of Chinese words and phrasing, Japanese words and phrasing, and whether there is indication of Japanese readings of Chinese terms

- Body techniques, shintai gihō 身体技法: whether written while held in a person’s hand or written upon a desk surface; indications of the writer’s penmanship

Left: Baba’s formula that mokkan are wood with ink and characters. Right: the four notable things to look for in wooden slips. Slides courtesy of Baba Hajime. Reprinted with permission.

Identifying these various aspects can give insight into not only the manufacturing of these items, but also what sort of person would have access to, for example, a particular calligraphic style or a specific type of brush. Word choices are also suggestive of the writer’s background, such as if they demonstrate greater fluency with Chinese-style phrasing or classical Japanese court terminology.

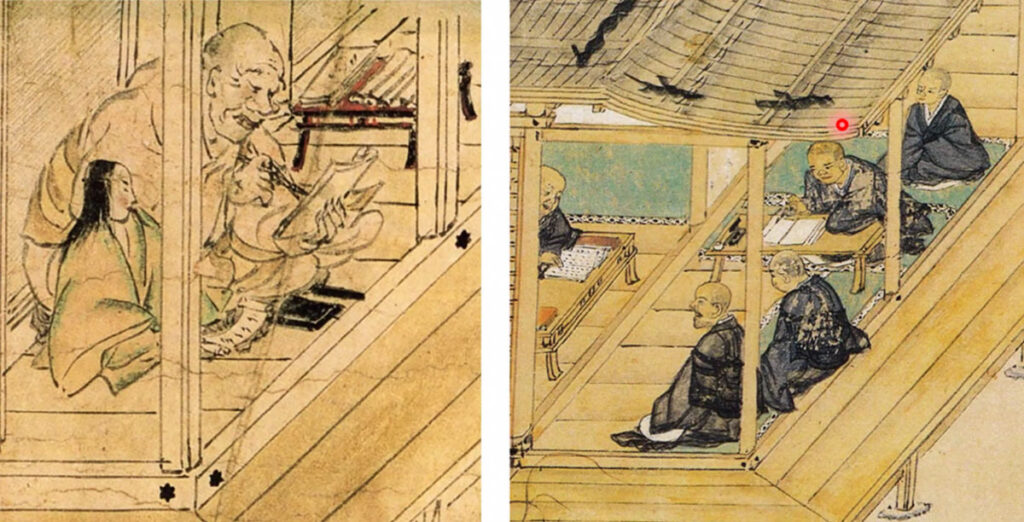

Baba particularly emphasized the fourth point about the writer’s body position as being an important consideration with written texts. Whether written against a hand or a desk, the characters themselves can vary significantly. Desk-based writing tends to be crisp and straight, similar in aspects to the Japanese katakana script. By comparison, writing done against a hand looks more fluid and connected, like the hiragana script. As with katakana and hiragana, these writing methods also had their distinct purposes. Baba noted that the desk-based writing was more apparent with Buddhist and Chinese texts, and the hand-based writing was used with literature and notes, including mokkan. In short, the difference in surfaces and body positions corresponded with not only traditional literary categories, but also with different uses for katakana and hiragana. These different poses may even have influenced the development of these writing systems.

Images indicating hand-held (left) and desk (right) writing styles. Slides courtesy of Baba Hajime. Reprinted with permission.

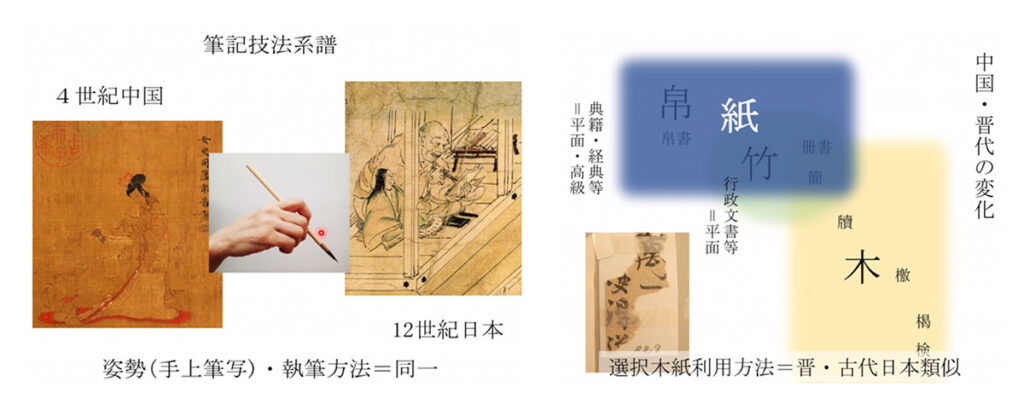

In addition to their connection in producing different types of literature, Baba argued that the handheld vs. desk-based writing reflected multiple writing traditions that developed in China and made their way into Japan via different streams of influence. For example, Baba showed a fourth-century Chinese painting depicting a scribe writing on a piece of paper held in his other hand. This figure was also using what is now considered to be a standard Japanese way of holding a brush. Similarly, geographical differences influenced which writing surfaces were used and for which purpose, especially following the development of paper manufacturing. Even as writing systems and technologies developed in China and were transported to Japan in later periods, the writing culture in Japan was sufficiently strong enough that certain established forms of writing—such as the manner of holding the brush and holding the writing surface in one’s hand—did not fade. Instead, some of these Japanese customs flowed back to the Asian continent through Korea, leading to some cross-influence as well as preservation of older techniques.

Left: Indications of styles for holding a brush as seen in fourth-century Chinese and twelfth-century Japanese images. Right: development of writing surfaces in China, namely fabric, bamboo, and wood, with paper overlapping fabric and bamboo. Slides courtesy of Baba Hajime. Reprinted with permission.

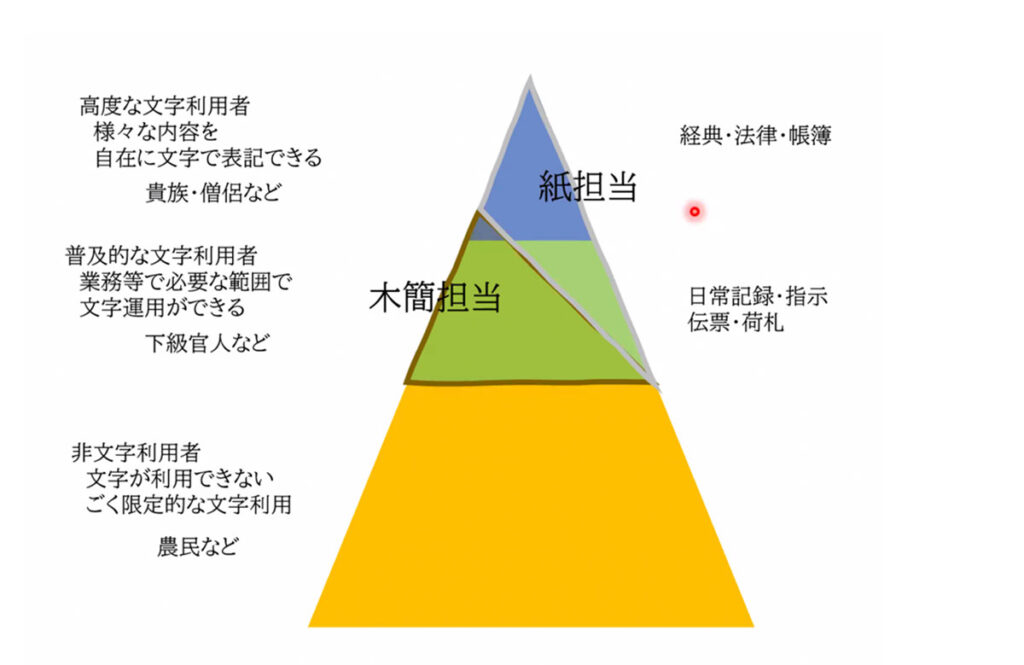

In order to better perceive both the circumstances for different kinds of writing surfaces and styles, Baba introduced a pyramid that reflects perceived privilege and literacy levels. He added the caveat that this was for heuristic purposes and, in reality, the writing categories were not quite so rigid. The top segment reflected pieces demonstrating a broader knowledge of characters and more fluid writing style, such as sūtras, laws, and ledgers. These would be written by the likes of aristocrats and Buddhist monks. In the middle were pieces used for essentials needs and business transactions, including receipts and shipping tags. These were created by middle- and lower-class people. At the bottom were those that show little to no knowledge of the characters or grammar, such as farmers and peasants.

A pyramid indicating overlaps between privilege and literacy, with paper-based and character-rich writings at the top, wood-based and moderate character usage in the middle, and little to no character use at the bottom. Slide courtesy of Baba Hajime. Republished with permission.

When looking at writing mediums, there is a skewed overlap between the upper two levels. Baba divided the use of paper between the two, but it was more commonly used in the highest tier. By comparison, mokkan predominantly belonged in the middle tier. This discrepancy accounts for part of the reason why there are not many mokkan related to Buddhist studies. What mokkan are found at Buddhist temple sites tend to be connected to construction and management, and they generally do not reflect higher level religious thought. Instead, they were likely written by or for the temple’s lay managers. Mokkan provide insight into the localization of Buddhism throughout Japan, including those examples that fall into the lower tiers on the literacy pyramid.

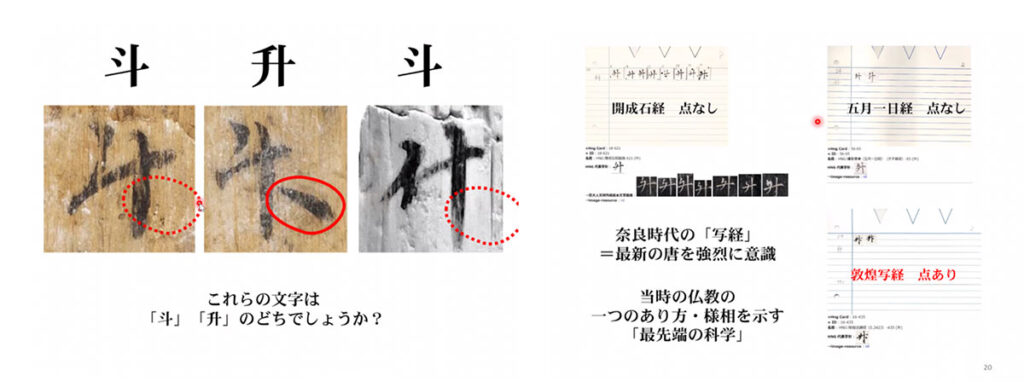

Baba then transitioned into a series of four mokkan case studies that indicate Buddhist influence. The first was a comparison of the characters for to 斗 and masu 升, both of which are used for volume. In the handwritten examples, the two are nearly indistinguishable with the exception of an extra stoke for masu. In mokkan, the extra stroke tends to be present, whereas it is absent from sūtras. In comparing examples of documents from China and Japan, Baba theorized that the stroke was dropped in eighth-century Japanese sūtra copies as monks adopted the latest writing techniques from China, something of which mokkan writers would not necessarily have been aware.

Left: images showing the to and masu characters, distinguished by the presence or absence of a stroke in the lower right corner. Right: literary examples from China and Japan demonstrating when the stroke in the masu character was dropped. Slides courtesy of Baba Hajime. Reprinted with permission.

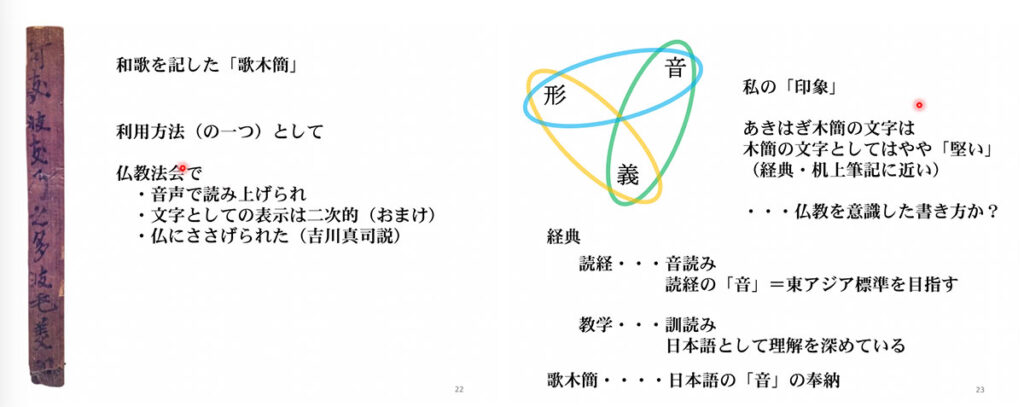

The second case study involved a famed example of a mokkan with a poem on it, an uta mokkan 歌木簡 from Kamiodera that was also discussed in the previous day’s lecture. At first glance, the comparatively crisp writing on this example works against Baba’s argument that mokkan were largely written while held in the hand and, as such, that the writing was more fluid and connected. However, Baba suggested that this writing style may reflect an underlying awareness of the Buddhist nature of the text and may mean that it was intended to be read aloud to a Buddha. If so, it would reflect a mindset that was typically applied to writing Buddhist texts that, in this case, was transferred to the less formal mokkan. Baba advocated for paying attending to the form, meaning, and sound of the characters and the intersection these three components in the piece’s creation and performance.

Left: image of and explanation behind the writing style on the uta mokkan from Kamiodera. Right: image demonstrating Baba’s argument concerning the overlap of a piece’s form, meaning, and sound. Slides courtesy of Baba Hajime. Republished with permission.

The third case study focused on kujibiki くじ引き, sticks used for drawing lots. Although intended more for entertainment than devotional purposes, these fortunes reflect a familiarity with Buddhist concepts and concerns. For example, one stick referred to the future buddha Maitreya’s world. The fourth case study was on bundles of kanju ita 巻数板, meaning “[wooden] boards listing the Buddhist scrolls that have been read”. Baba also referred to these as kanjō ita and indicated that these may have been related to kanjō nawa 勧請縄, ropes used to demarcate a village borders for protection against evil spirits. The kanju ita stated how many sūtras the people there had read, functioning like a talisman against spirits and plagues by invoking the protective powers of the Buddhist pantheon. The kanju ita and their relationship to kanjō nawa tied in with previous discussions on combinatory religious practice and also provide insight into religious practices and beliefs of rural areas far from political and religious centers.

Left: examples of kujibiki from Saidaiji. Right: a kanju ita listing Buddhist scrolls that had been read by the village inhabitants. Slide courtesy of Baba Hajime. Reprinted with permission.

Conclusion:

In the first talk, Professor Kondō referred to the excavated sources with writing as “raw materials”, or nama no shiryō 生の史料, which was a phrase that was revisited throughout subsequent discussions. Unlike official histories, whose narratives were sculpted and refined by generations of editors, these items were never intended to contribute to posterity. While limited in scope, they nonetheless can be used to support or even undermine the very texts that have traditionally shaped collective understandings of the past. Moreover, these sources provide glimpses of people who are rarely mentioned in histories and temple records, including women and commoners. Additionally, they provide tangible evidence of how Japan’s written language developed and was used outside of erudite settings. As such, they challenge conceptions of “literature” and “literacy.”

One point made clear throughout the talks is how important the physicality of the excavated sources with writing are. While they are not the only sources that date back to the seventh and eighth century, they are among the only remaining written items that were actually created during those periods. The vast majority of original historical and literary texts that were created during these times are lost, and what remain are the descendants of generations of copies that were duplicated and passed down. With their physicality long gone, what remains is their written content. The opposite is true in the case of the excavated sources with writing. With relatively few exceptions, no single item has enough written material to draw meaningful conclusions on the basis of the writing alone. But they have historical value and significance when taken into consideration of the contemporaneous texts and other items found with and near them. Additionally, there is more information available by analyzing the manner in which characters were written, the tools and implements used to construct them, and the tangible qualities of their writing surfaces.

Dr. Abigail MacBain is a recent graduate of Columbia University’s Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures. She specializes in early Japan’s overseas relationships and Buddhism’s transmission to Japan through Silk Road trade and communications. Her current research explores how cultural expressions such as music, dance, and art increased the Japanese court’s global awareness and understanding of other countries and peoples. In Autumn 2022, she joined the Asian Studies Department at the University of Edinburgh as a lecturer of Pre-modern Japanese Studies.

Click here to view the original post.