我們很高興地宣布一本新書: 郝春文 Dunhuang Manuscripts: An Introduction to Texts from the Silk Road 《石室寫經——敦煌遺書》者,太史文翻譯,Portico Publishing 公司 2020 年出版。

Dunhuang Manuscripts: An Introduction to Texts from the Silk Road

《石室寫經——敦煌遺書》

郝春文

太史文翻譯

序

太史文

Dunhuang Manuscripts—an accidental assembly of more than 60,000 pieces of writing, ranging from long books in scroll format to short jottings on single sheets or fragments of paper—are a historian’s dream. Hao Chunwen’s 2007 introductory book, here revised and translated into English, opens up the full range of those documents. Written for the educated general reader, this book offers an unrivaled understanding of the diversity of medieval Chinese social life and the richness of cultural interaction along the silk road. This preface provides an overview of the Dunhuang manuscripts and their significance, the virtues of Hao’s book and the choices made when translating it into English, and the roles played by author and translator.

The Dunhuang corpus constitutes not so much a library but rather a haphazard gathering together of written material circulating in a medieval city over a span of more than 600 years. It is true that more than 90% of the texts are sacred scriptures that belonged to Buddhist monasteries. But in addition to sūtras from the shelves of well-ordered temple libraries, there are also writings used in local schools, private libraries, government offices, and by merchants passing through this key oasis intersection.

We may never know why all these materials were gathered up early in the eleventh century and then entombed until a local caretaker of the Mogao cave-temples in the desert outside of Dunhuang happened to discover them in the year 1900.Debate about the reasons for the sealing of the so-called library cave still rages. Responsible scholars have suggested different motives: a genizah for sacred waste, fear of impending invasion, interment to survive religious decay, memorializing a local holy man, relocation of a single monastic library.

Regardless of how the mystery of their burial is solved, however, this book accentuates the astounding diversity of the Dunhuang manuscripts and the amazing new light they shed on the past. Most of the Chinese historical record was produced over the millennia by professionals tasked with writing about the past to teach a lesson to those in power. By contrast, the Dunhuang corpus came together accidentally.The Dunhuang materials include, to be sure, medieval versions of the standard histories studied at the time, including Records of the Grand Historian, History of the Han Dynasty, Records of the Three Kingdoms, and History of the Jin Dynasty. But they also contain non-standard versions of many of the histories as well as otherwise unknown works, including biographies, military histories, and textbooks for teaching history in local schools. Diversity and the chance survival of otherwise unknown texts are true for all the categories of traditional Chinese writing found at Dunhuang.

Another way to think about the remarkable diversity of sources discovered at Dunhuang is to consider social class and levels of literacy. Elite culture is represented in the dozens of Lotus and Diamond Sūtras produced by scribes in the imperial court as part of the official copying and empire-wide promulgation of canonical Buddhist texts in the seventh and early eighth centuries. There are also more than twenty manuscript copies, some with annotations and notes on pronunciation, of the erudite anthologySelections of Refined Literature (Wenxuan 文選) by Xiao Tong 蕭統 (501-531), copied at Dunhuang between the sixth and ninth centuries.Middle-brow culture is also abundant. Primers used in local schools, including many whole texts unknown before the Dunhuang discoveries, together with sheets of practice characters and handwriting exercises, provide insight into how students learned to read and write during the medieval period. Practical documents from daily life also show how the barely literate engaged in technical, legal, and religious activities. The Dunhuang corpus contains texts for counting numbers and figuring out the calendar; contracts for rent and sale of grain, cloth, and land, or the services of servants and slaves; wills and divorce agreements; and memos announcing meetings of lay Buddhist congregations that were circulated among members and required people to check their names off a list before passing them to the next member. Many such memos and wills bear incorrectly formed names, pictorial signing marks, check marks, lines, fingerprints, or knuckle-imprints in place of a signature.

Like other experts in Dunhuang studies, Professor Hao is careful in this book to reflect on the interplay between Dunhuang’s local culture and the broader world, including the Chinese imperial forces emanating from Chang’an far to the east and the significant, sometimes overpowering cultures, city-states, and empires to the south and west, including the Tibetan empire and Uyghur kingdoms. The town of Dunhuang had been established as a garrison for Han-dynasty (206BCE-220 CE) troops in the second century BCE. It was the westernmost town in a string of oasis-towns marking the east-west passage (the Hexi Corridor)situated between the Gobi Desert to the north and the Tibetan Plateau to the south. Moving westward, once past Dunhuang, travelers would choose between northern or southern routes skirting the edges and following water sources of the Taklamakan Desert. Following the influx of Han people from central China, the city’s demography underwent change in both numbers and ethnic make-up.During the centuries under discussion in this book, the area was successively under control by different dynasties, including Northern Liang (397-460), Northern Wei (386-550), Sui (581-618), Tang (608-907), Zhou (690-705), Tibetan rule (786-848), various regimes of the Five Dynasties (907-960), and Song (960-1275). For the period 848-1036, Dunhuang was essentially the seat of power for the quasi-independent Return to Righteousness Army, which reclaimed most of the Hexi Corridor from Tibetan control and vowed loyalty to Chinese regimes in central China.

The ethnic and cultural pluralism of this part of western China is also reflected in the linguistic diversity of the Dunhuang manuscripts. Although most were written in Chinese, a significant number of other languages used in central Asia are also represented. Some 8,000 of the roughly 60,000 manuscripts were written in Tibetan, ranging from multiple copies of canonical scriptures to records of religious debates, census data, land contracts, and other documents used by the Tibetan imperial administration. Recent scholarship has shown that for a few centuries after the period of rule by Tibet, Dunhuang remained essentially a bilingual environment, supporting translation activities, cultural interaction, and intermarriage. Manuscripts written in Uyghur (Old Turkish) also survive at Dunhuang, traceable to nearby Uyghur regimes to the east and west of Dunhuang as well as Uyghur-speaking residents in Dunhuang itself. Khotanese, an ancient Iranian language, is also attested, since in the tenth century the ruling family of the area, surnamed Cao 曹, was related by marriage to the king of Khotan. Khotanese texts include Buddhist scriptures, medical texts, literary works, administrative reports, and works of geography.

The chance collection of texts and their improbable survival across the centuries at Dunhuang also open a unique window into local variations, non-canonical practices, and banned religious movements that show up nowhere else in the historical record. The standard histories and official compilations of government reports known from printed or transmitted sources explain, for instance, how property was supposed to be divided and how taxes should be collected. But the Dunhuang documents show exactly how land was measured, recorded, and taxed, how local populations were counted, how practice diverged from proclamation. Dunhuang was a small city with a large presence of government offices (whether under control of the Tang, the Tibetans, or the Return to Righteousness Army) and a relatively large number of Buddhist monasteries. These institutions exerted significant control, followed national or trans-regional protocol, and mandated the production and dissemination of texts. The Dunhuang corpus certainly exemplifies the regulatory functions of state and church, but at the same time it divulges how much of medieval social life exceeded these boundaries. Texts that were never supposed to have been written survive among the Dunhuang manuscripts, including local calendars for planting and sacrifices. Similarly, scriptures produced by outlawed religious sects are in abundance, as are books excluded from the official canons of Buddhism and Daoism.

Dunhuang Manuscripts, the book, is an introduction to medieval China and the silk road focusing on the content, form, and significance of the manuscripts discovered at Dunhuang. It is intended for general readers, students, and teachers who may not know Chinese or who lack direct access to the primary sources and the considerable body of modern scholarship written in Chinese and Japanese. This book takes the reader through the primary sources, placing them in the context of Chinese history, the interaction of cultures along medieval trade routes, and the discipline of history of the book. This book is also designed to introduce the full range of subjects covered in the Dunhuang documents to readers who may have begun with a more specialized interest, such as Chinese literature, manuscript culture, Buddhist studies, or the history of Chinese medicine. Aside from listing important secondary studies in the Bibliography, this book does not pile on references to scholarship on each subject—for that, an English translation of Rong Xinjiang’s Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang is happily now available. Nor does this book provide guidance for finding and reading the original manuscripts, skills which are best developed through seminars and workshops.

The first edition of this book was published in Chinese in 2007 under the title Manuscripts from the Stone Cavern: The Legacy of Dunhuang. A Japanese translation by Yamaguchi Masateru and Takata Tokio was published in 2013; and a second, revised edition published in Chinese in 2016. Our English translation is based on the original edition of 2007, with some changes and updating.

The original book has many strengths which we have endeavored to reflect transparently in this English version. Perhaps the book’s greatest virtue is that it is aimed at an educated reader with no specialized knowledge of the subject. It is sophisticated and urbane, elegant and unpretentious. Its style is witty, it is filled with wisely-chosen examples, it has lots of great pictures, and it contains no footnotes.

Another strength of the book is its sophisticated approach to the Chinese past.History, it is said, is never not written from the perspective of the nation-state or empire, even when its subject is international or transregional. This truism applies three times over to the field of Dunhuang studies. In the first place, the manuscripts themselves boast a variety of nation-states, languages, and cultures occupying the edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the six centuries before the year 1000. This naturally raises the question: to whose history do the manuscripts speak? What people’s—which nation’s—story do they tell?

A second sward of national interest started to grow in the year 1900. The manuscript hoard hidden in a cave at Dunhuang was uncovered by a citizen and former soldier of the Qing dynasty (1636-1912), Wang Yuanlu (ca.1850-1931), who was bribed by representatives of imperial governments—first Britain, then France, then Russia. Between 1907 and 1915, together with a private, non-governmental expedition from Japan, the foreign teams carried off as many as 46,000 manuscripts and placed them for safe-keeping in the British Museum, the Bibliothèque nationale, the Asiatic Museum in St. Petersburg, and elsewhere.The balance of roughly 14,000 documents remained in China. Based on the manuscripts held in Beijing, the first general catalogue of Dunhuang manuscripts was compiled by the historian of religion Chen Yuan 陳垣 (1880-1971) in the year 1931. Its title reflects what is still the mainstream attitude in China: Catalogue of Manuscripts from Dunhuang Remaining after the Theft (Dunhuang jieyu lu 敦煌劫餘錄). In respect to this phase of national and international history, the debate is ongoing. Who owns the Dunhuang manuscripts? Are they part of China’s cultural heritage? Or Britain’s? Or France’s? Or Russia’s?

Yet a third dimension of national history involves the modern scholarly worlds taking part in the study of Dunhuang manuscripts. In part owing to their far-flung dispersal, manuscripts from Dunhuang have occasioned an unusually broad international industry of scholarship.

In all three respects, Hao Chunwen’s Dunhuang Manuscripts offers important insights about the writing of history. The book unabashedly represents the position of most educated Chinese toward the invasion of their country at the end of the Qing dynasty and the carting away of cultural loot. As translator, I have chosen to let Hao’s words speak for themselves: chicanery, booty, bribe, steal, swindle, loot, plunder. This book is also based on the broadest and deepest foundation of secondary scholarship on the Dunhuang manuscripts, that produced by scholars in China since the ending of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). At the same time, the author and the book are committed to international cooperation, including with scholars and scholarship in Japan and the West.

In addition, the book follows Dunhuang manuscripts into every intellectual domain and genre in which they appear, including canonical and non-canonical religious texts from Buddhism, Daoism, Syriac Christianity (Nestorianism), Manichaeism, and Zoroastrianism; documents written by officials at all levels of the medieval Chinese government, including legal documents; economic sources such as household registers, registers of corvée and taxes, and contracts; geographical treatises and travel records; documents for social history, including clan genealogies, letter writing manuals, documents for local religious associations, financial records from Buddhist temples, and liturgies used in religious rituals; popular literature with significant admixtures of the vernacular language such as prosimetric forms that accompanied picture storytelling, lectures on sūtras, and various forms of vernacular poetry; scientific and technical literature dealing with medicine, astronomy, calendars, divination, mathematics; as well as the division of traditional sources into the categories of classics, histories, philosophers, and literary collections. This is a breathtaking range of writing, its authors ranging in time from 500 BCE or earlier to 1000 CE. Dunhuang texts cover most disciplines of knowledge and include many styles of writing, from the most formal to the most practical.

Hao Chunwen’s book not only introduces examples from each of these genres; it is also based on his intimate knowledge of both the texts (the words on the page) and the physical features of the manuscripts (the paper on which the words are written). The book grows out of thirty years of first-hand study of most of the manuscripts cited herein.

Rendering the original into a style of English calibrated for an educated, general reader who does not command Chinese has been my highest goal. For many sentences, this was not so hard, because of the clarity of the source. Other sentences, however, required more active intervention. A persistent challenge was translating the titles of books both premodern and modern; often I succeeded only after reading the original source itself. The biggest difficulty came in translating the abundant citations of primary texts from the original Chinese. Suffice it to say that both author and translator have learned much about the original texts and their language through collaborating on this book.

A second desideratum in presenting this book in English to general readers was to add background information. This was intended to help non-Sinologists appreciate the nuances of the book’s twenty-first century interpretative stance as well as the significance of the many ancient and medieval source texts from which the book quotes. Chinese readers would of course understand the book against a lifetime of education and insider’s cultural knowledge. But we could not assume readers of the English translation shared that background. Consequently, I have filled in some of the epistemological framework when presenting the same material to a Western audience. Hence, this English edition of the book includes a not inconsiderable amount of supplement and background. These interventions concern modern Chinese culture as well as ancient and medieval history, literature, philosophy and religion, and science and technology. I have also appended a skeleton Bibliography of works in Western languages to point readers to possible next steps in their reading.

As translator of this project it has been a pleasure to work closely with the author. Although we each bear different titles in the production of the book, in actuality our roles often overlapped.

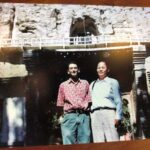

I have known Hao Chunwen since 1999, when we took part in a fieldwork project on Buddhism, social history, art, and archaeology. Our group of six scholars from China and six from the USA began at Dunhuang and other medieval Buddhist sites in Gansu province and moved on to locations throughout Sichuan. For one month we traveled together by mini-bus, read each others’ books, and debated the inscriptions, paintings, texts, and architecture in front of us. This was a great foundation for a long-term collaboration.

Professor Hao is Distinguished Professor at Capital Normal University, having earlier served as Professor and Dean of its School of History and as Professor at Shanghai Normal University. Since 1997 he has written and edited numerous books, ranging from monographs on the social and institutional history of Buddhism to meticulous editions and annotations of original Dunhuang documents. He has also led numerous collaborative research projects that cross borders, ranging from editing the major Chinese-language journal in the field to organizing international coordinating committees.

For the past twenty years Professor Hao and I have lectured at each others’ universities, taught each others’ students, and worked together on research.Thanks to funding from the Glorisun Global Network for Buddhist Studies and the support of the Buddhist Studies Workshop at Princeton University, he was able to spend a semester at Princeton in 2018-19, which allowed us to hash through the difficult portions of the translation.

In preparing this book for publication, we have also relied on significant help and advice from two other scholars. Luke Waring, who completed a Ph.D. in early Chinese literature and history at Princeton University in 2019, offered fastidious help throughout the project. In the final stages we also relied on the expertise of my colleague in Princeton University’s Department of EastAsian Studies, Wen Xin; we are grateful for his careful reading of the manuscript, which helped avert many gaffes and glitches.

The collaboration between author and translator has been rewarding intellectually and personally, a synergy we hope is reflected in the book. Stated simply: Hao brings expertise in paleography and social history, while Teiser has background in Buddhist studies. We have learned much from each other, and we hope that the resulting product is greater than the sum of our individual contributions.

目錄

Preface By Stephen F. Teiser

Abbreviations

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

The Legacy of Dunhuang

CHAPTER 2

Overview of the Manuscripts

Contents

Time Span

Textual Format

Binding Format

Languages

CHAPTER 3

Amount and Current Disposition of the Manuscripts

Contents and Significance of the Dunhuang Manuscripts

CHAPTER 4

Religious Texts

Buddhism

Daoism

Other Western Religions

CHAPTER 5

Historical and Geographical Texts

CHAPTER 6

Documents for Social History

CHAPTER 7

Popular Literature

CHAPTER 8

Scientific and Technical Writings

CHAPTER 9

Four Classes of Ancient Texts

Classics

Histories

Philosophers

Literary Collections

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

Chinese Language Studies

Western Language Works and Reference Works

Index

Index of Manuscripts and early Printed Editions

《石室寫經—敦煌遺書》簡介

敦煌古代文化遺產是世界文化遺產。早在1987年,在中國第一批被列入世界文化遺產名錄的名單中,就有敦煌莫高窟。所以,敦煌在世界上知名度很高。很多外國人不知道中國有甘肅省,但知道敦煌。

敦煌古代文化遺產主要包括敦煌莫高窟和藏經洞出土的敦煌遺書。雖然被列為世界文化遺產的是敦煌莫高窟,但敦煌學的形成卻主要是因為敦煌遺書的發現。現在,以敦煌遺書、敦煌石窟藝術、敦煌史蹟和敦煌學理論為主要研究對象的新興交叉學科敦煌學已經成為一門國際顯學。在國際學界乃至文化界都有重大影響。

敦煌遺書是1900年6月22日,道士王圓籙在敦煌莫高窟第17發現的從十六國到北宋時期的經捲和文書。這批古代文獻總數在六萬件以上,多數為手寫本,也有極少量雕版印刷品和拓本;其形態有捲軸裝、梵夾裝、經折裝、旋風裝、蝴蝶裝、包背裝、線裝和單片紙葉等;其文字多為漢文,但古藏文、回鶻文、于闐文、粟特文和梵文等其它文字的文獻亦為數不少;其內容極為豐富,涉及宗教、歷史、地理、語言、文學、美術、音樂、天文、曆法、數學、醫學等諸多學科,但以佛教典籍和寺院文書為主。不論從數量還是從文化內涵來看,敦煌遺書的發現都可以說是上一世紀中國最重要的文化發現,對了解中國中古時期的歷史和中西文化交流史具有無可替代的價值。

《石室寫經—敦煌遺書》用通俗易懂的語言,向讀者全面介紹了敦煌遺書的發現、概況、收藏情況及其具體內容。

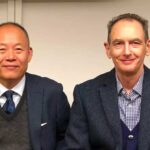

郝春文和太史文

郝春文

Hao Chunwen 郝春文 is distinguished professor of History at Capital Normal University 首度師範大學 and serves as the head of the university’s Center for the Study of Ancient Literature. He received his Ph.D. in History from Capital Normal University in 1999.

Hao’s primary fields of research are Dunhuang Manuscripts and Buddhism in China. He is also broadly interested in premodern Chinese History, with a particular focus on the period 200-1400.He has published several monographs and annotated primary source collections on related topics, including Zhonggu shiqi sheyi yanjiu 中古時期社邑研究 (Research into the Associations of Medieval China), Tanghouqi Wudai SongchuDunhuang sengni de shehui shenghuo 唐後期五代宋初敦煌僧尼的社會生活 (The Social Life of Buddhist Monks and Nuns in Dunhuang inthe Late Tang, Five Dynasties, and Early Song), Shishi xiejing: Dunhuang yishu 石室寫經——敦煌遺書 (Manuscripts from the Stone Cavern: The Legacy of Dunhuang), Dunhuang de lishi he wenhua 敦煌的歷史和文化 (The History and Culture of Dunhuang) (co-author), and Dunhuang sheyi wenshu jijiao 敦煌社邑文書輯校 (Collection of Edited Documents from Dunhuang Related toAssociations) (co-authored). His current project, sponsored by the National Social Science Fund of China, investigates Dunhuang documents kept in the U.K.and collects and studies primary sources related to social history. The outcome of this project will be a 30-volume series Yingcang Dunhuang shehui lishi wenxian shilu 英藏敦煌社會歷史文獻釋錄 (Annotated Transcription of Dunhuang Documents concerningSocial History Preserved in the U.K.), of which 15 volumes have already been published.

Hao is the president of the China Association of Dunhuangand Turfan Studies and serves as chair and committee member of many academicorganizations. He is the chief editor of Dunhuang Tulufan yanjiu 敦煌吐鲁番研究 (Journal of Dunhuang and Turfan Studies) and Dunhuangxue guoji lianluo weiyuanhui tongxun 敦煌學國際聯絡委員會通訊 (Newsletter of the International Liaison Committee for Dunhuang Studies), and serves on the editorial board of Zhongguo shi yanjiu 中國史研究 (Journal of Chinese Historical Studies). Believing that academic exchange and collaborations inspire new ideas, he is an organizer and active participant in academic conferences and other projects. He has lectured widely at home and abroad, including at Peking University, Nanjing Normal University, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, National Chung Cheng University, Princeton University, Harvard University, Yale University, and The University of British Columbia.

Hao began his teaching career at Beijing Teachers’ College in 1986, and later joined Capital Normal University. In 1994, he was promoted to full professor for his special contributions in research and teaching. He has taught many courses for both graduate and undergraduate students, such as “Premodern Chinese History,” “The History of Sui, Tang, and the Five Dynasties,” “Introduction to Dunhuang Studies,” “Studies of Dunhuang Documents,” and “Topics in Theory and History.”

Stephen F. Teiser and Hao Chunwen at the Yulin Grottoes (榆林窟), in 1999

太史文

Stephen F. Teiser is D.T. Suzuki Professor in Buddhist Studies and Professor of Religion in the Department of Religion at Princeton University. His work focuses on Buddhism and Chinese religions, tracing the interaction between cultures through textual, artistic, and material remains from the Silk Road. He also serves as Director of Princeton’s interdepartmental Program in East Asian Studies, and in 2014 he received the Graduate Mentoring Award in the Humanities from Princeton University’s McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning,

Teiser’s forthcoming book from Sanlian Publishers, based on the 2014 Guanghua Lectures in the Humanities at Fudan University, is entitled 儀禮與佛教研究 (Ritual and the Study of Buddhism). His main research to date appeared in three monographs: Reinventing the Wheel: Paintings of Rebirth in Medieval Buddhist Temples (2006), awarded the Prix Stanislas Julien by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, Institut de France; “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism (1994), awarded the Joseph Levenson Book Prize (pre-twentieth century) in Chinese Studies by the AAS; and The Ghost Festival in Medieval China (1988), awarded the prize in History of Religions by the ACLS. He has also edited several books, including Readings of the Platform Sūtra (2012) and Readings of the Lotus Sūtra (2009).

Teiser earned an A.B. at Oberlin College (Ohio) and received M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Princeton University. He has held teaching appointments at Middlebury College and University of Southern California, and has been visiting professor at Écolepratique des Hautes Études (Paris), Heidelberger Akadamie der Wissenschaften, and Capital Normal University 首都師範大學 (Beijing). He has received fellowships and grants from numerous organizations, including American Council of Learned Societies, E. Rhodes and Leona B.Carpenter Foundation, Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation, Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation, Henry Luce Foundation, Andrew Mellon Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities, Silkroad Foundation, Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and Social Science Research Council.

原始發帖: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/RPU8j-ZdyEqxA6yhLU6zrg