By Saly Sirothphiphat

FROGBEAR project’s cluster 3.4 Typologies of Text-Image Relations was led by Christoph Anderl, in collaboration with Marcus Bingenheimer, Oliver Streiter, Tzu-Lung Melody Chiu, Ngar-sze Lau, and Yoann Goldin. The project took place from May 24 to June 2, 2023, in the beginning of Bangkok’s monsoon season. One of the project’s goals was to follow the footsteps of Wolfgang Franke, a German sinologist, who travelled to Thailand to document Chinese inscriptions at different Chinese religious spaces several decades ago, and later published the photos he took. The cluster participants were organized into smaller groups and were assigned with different inscription photos taken by Franke. Their tasks were to revisit places that Franke trekked and to photo-and-video document additional Chinese religious spaces that he might not have visited. These tasks were designed to give a better understanding of, if not illuminate, Franke’s choices of space and inscription. In other words, what might have been Franke’s reasons for including and leaving out some inscriptions and sites. Another goal of the project was to provide accessible online data gathered from this fieldwork’s documented Chinese religious spaces in Bangkok in the form of 360-degree videos, detailed photos, and interview accounts with the locals to interested individuals. Throughout the program, the use of advanced technological documentation of the spaces and the emphasis on digital humanities were also central to the participant practices and ways of conducting fieldwork.

May 23, 2023

Cluster participants and leaders arrived in Bangkok, Thailand and checked in at the hotel at their convenience. Most participants stayed at Shanghai Mansion (เซี่ยงไฮ้แมนชั่น, pronounced Sianghai mansion) Bangkok on Yaowarat road (ถนนเยาวราช, pronounced Thanon Yaowarat), which is the main road in Bangkok’s Chinatown neighborhood. Instead of “Chinatown,” the local Thai people call the neighborhood “Yaowarat” after the road. At night, hundreds of hanging neon signs in assorted sizes and colors light up, turning the already busy road into an even more bustling and vibrant one. Pop-up restaurants, together with all sizes and all sorts of food stalls and carts, quickly filled both sides of the road which was already lined with restaurants during the days. While cars on the street were often forced to stop due to the traffic jams, tourists and locals never ceased their activities. People were walking, browsing food stalls, eating while walking or at pop-up food stalls, taking photos, asking for donations, selling lottery tickets, busking, and just having a good time. As I made my way along both sides of the street, I could barely hear anyone speaking Thai, apart from the shop keepers and food sellers.

When entering my room on the fourth floor, I met my roommate for the first time. She is Chinese and at that time was about to graduate with a master’s degree in England. As a descendant of Overseas Chinese in Thailand, I found that we share many values while have so much to learn from each other. We talked about how the architecture and interior design of the hotel looked very orientalist. By orientalist, we meant it was as if the hotel designers built and decorated the place according to the western imagination of Chinese styled dwellings and furniture. The place did not look like anything Chinese I saw in Beijing or Hangzhou. My roommate also completely agreed. But this was simply our observation and opinion based on our experiences. We thought it would be interesting to consider the question: where did the Thai imagination of what was considered to be Chinese come from, given that many Thais are of Chinese origin and emigrated before the state’s enforcement of social assimilation that shaped and made Thainess? We fell asleep, talking about ghosts, spirits, and haunting stories, which are Thais’ favorite topics of discussion. Little did we know that our journey during the fieldwork in Bangkok would add many more sticky layers and meaningful complexity into the way we view Thailand and its people’s religiosity.

The room in Shanghai hotel in which my roommate and I stayed during the fieldwork (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

May 24, 2023

After breakfast, we all grouped up and got Grab (an Uber-like service in Thailand) to Thammasat University Pridi Banomyong International College (มหาวิทยาลัยธรรมศาสตร์วิทยาลัยนานาชาติปรีดีย์ พนมยงค์, pronounced Maha vittayalai Thammasat Vittayalai nanachat Pridi Panomyong, or Thammasat University hereafter). It took us around fifteen minutes to get to the university despite the driver saying, “it depends on the traffic.” Thammasat University is located on the eastern bank of Bangkok’s main river—the Chao Phraya (แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา, pronounced Mae-nam Jao-praya).

To begin the official fieldwork, Professor Christoph Anderl (Ghent University) gave a talk to FROGBEAR participants, translators, Thammasat University professors, and interested individuals. At Thammasat University, different researchers, such as Dr. Thomas Bruce, Dr. Paul McBain and Dr. Omthicha Duangratana, welcomed FROGBEAR participants. Then, Professor Marcus Bingenheimer (Temple University) presented basic information about Bangkok, and introduced the audience to the city’s districts, religiosities, population, ethnicities, and languages. Professor Oliver Streiter (Kaohsiung National University, Taiwan) presented his works on tombstone tracings in Northern Thailand to show the data collection of how the Thai-Chinese’s knowledge of Chinese language may fade over time, and fieldwork experiences with locals.

Tzu-Lung Melody Chiu 邱子倫 (National Chengchi University, Taiwan) presented ethnographic research on oversea Chinese’s funerals, their materiality, and ethnographic research methods that can be applied to fieldwork. Dr. Paul McBain presented the project of digitalizing Thai temples and introduced the audience to a wide range of tools and programs in terms of prices and abilities that can help digitalize temples and space.

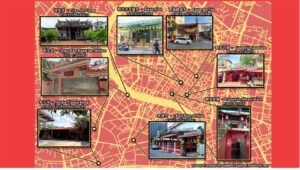

After the helpful and informative lectures, participants and leaders chose the group they wanted to join. There were five groups and each focused on a different deity. The five deities included Bentougong (本頭公) or Pun Tao Gong (ปุนเถ้ากง), Tianhou (天後) or Chao Mae Tubtim (เจ้าแม่ทับทิม), Xuantian (玄天) or Chao Po Suea (เจ้าพ่อเสือ), Guanyu (關羽) or Thepa Chao Guan Yu/Chao Po Guan Yu (เทพเจ้ากวนอู/เจ้าพ่อกวนอู), and Guanyin (觀音) or Chao Mae Guan Yim (เจ้าแม่กวนอิม). Consisting of one leader (a professor), one translator (a speaker of Thai, English, and some Chinese), and 2–3 students, each deity group received its own list of eleven to twenty temples/shrines/foundations to visit.

After a long day of lectures and introductions to Thailand, religions in Thailand, and helpful technology in fieldwork, we all headed to a pier nearby to take a ferry to Iconsiam (ไอคอนสยาม, pronounced Iconsayam), a mall on the western bank of the Chao Phraya, to get on a cruise. Some participants mentioned that Bangkok is so diverse that each area seems to have its own style and uniqueness. This was prompted by the fact that Chinatown, Thammasat University, the pier we were standing at, and the other side of the river all looked like completely different zones with distinct characteristics. The ferry trip took around twenty minutes and saved us from Bangkok’s terrible traffic during rush hour. We then arrived at the Iconsiam shopping mall which just opened in 2019 and has welcomed tourists of various nationalities every day since—except for its closure at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. We then waited to board our cruise and got to spend more time getting to know other participants and group members.

On the cruise participants got a glimpse of Bangkok along the Chao Phraya; different bridges, buildings, architecture, temples, hospitals, and so on. After the cruise, participants got off and took different means of transportation to get back to the hotel. Some participants and I took a tuk-tuk back to Chinatown. The long first day of the program ended with exhaustion, enjoyment, and excitement.

The welcome and presentation at Thammasat University conference room on the first day (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

A bridge seen from the dinner cruise on the Chao Phraya (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

May 25, 2023

Participants met up for breakfast at the hotel lounge before starting their first day of fieldwork. Our group consisted of one professor (Christoph Anderl) and three students (Kira Johansen, Saly Sirothphiphat, and Oliver Thomson). Starting at 10am, for our first fieldwork site we decided to go to one Guanyin temple near the hotel. It was only a ten-minute walk. This was a deliberate decision. The strategy was that we would first visit all the Guanyin temples/shrines that Wolfgang Franke had documented, and then other Guanyin sites later. Also, starting off with a closer site allowed us to fix any mistakes. If something went wrong (as in forgetting to take a photo of something or forgetting to ask some questions in an interview), we would easily be able to go back to recollect the needed data.

The first temple we visited was Guanyin Gumiao (觀音古廟) or Aa Nia Keng shrine (ศาลเจ้า อาเนี้ยเก็ง pronounced San chao aa nia keng or ศาลเจ้า แม่กวนอิมฉือปุยเนี่ยเบี้ย pronounced San chao mae guan im chi pui nia bia) which is a phonetic Teochew 潮州 reading in Thai scripts. It was a small shrine with multiple nooks, altars, objects such as big drums, small drums, Guanyin figures at the main altar, various other Guanyin figures, Guanyin’s two helper statues on the left and on the right, divination leaves, divination bamboo box with numbered sticks inside, candles, banners, and paper burners. On one wall, Princess Sirindhorn or Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn (กรมสมเด็จพระเทพรัตนราชสุดาฯ สยามบรมราชกุมารี)who visited the shrine several years ago. The caretaker pointed us to the photo to see how respectable, old, and reliable this shrine is, commenting that “even Phra Thep [what Thai people call Princess Sirindhorn] came here!”

This shrine has a Thai spirit house and a statue of Goddess Dhāraṇī or Phra Mae Dhāraṇī (พระแม่ธรณี pronounced Pra-mae Tor-ra-nee) wrinkling her hair from the enlightenment scene of the Buddha’s life story. The co-existing deities and powerful figures, regardless of different religious traditions, point out that multiple realities can exist in the same space for the Thai worshippers. The caretaker told us that the owner of the shrine works somewhere else, and he was hired to take care of it. People walking by were happy to share any story and anything they knew regarding the shrine with us. The food stall seller told the renovation story when they found the inscriptions on the wall at the entrance of the shrine. We realized that Franke would not have encountered these inscriptions as they were discovered after his visit. The coffee shop owner across the street told us how this shrine precedes his father and grandfather. Sometimes, when the caretaker did not know the answer, he would look outside the shrine and yell “MOM!” Then, an older lady—who we assumed to be his mother—came to help him with the questions. Yet, she did not talk directly to us.

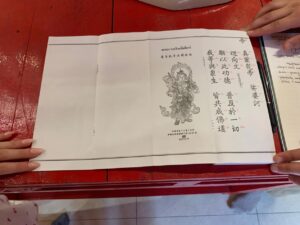

No one we conversed with spoke Mandarin Chinese or any Chinese dialect. One of the people walking by told us that most older people speak Teochew (แต้จิ๋ว pronounced Tae-jew). We saw this reflected in the phonetic reading of Chinese characters in the chanting books. For example, the character 生 (sheng) which would be pronounced with first tone in Mandarin Chinese, is accompanied by red Thai writing เซง (seng) which is the Teochew pronunciation of the same word. We asked to buy the red chanting books, but the shrine caretaker said that they are not for sale. This was an interesting point and information because as we proceeded with our fieldwork and research, we would receive varied reasons and answers from different Guanyin shrine caretakers.

From left to right: Professor Christoph Anderl, Oliver Thomson, Saly Sirothphiphat, Kira Johansen in front of the Guanyin Gumiao (觀音古廟) in Chinatown area (photo courtesy of Christoph Anderl).

Comparing today’s photo with that of Franke’s. Slide by Kira Johansen. Republished with permission.

People and everyday activities surrounding the Guanyin shrine. Some people would put their hands together in a praying manner when walking past the shrine. Here, there was a small pop-up food stall with seats in front of the shrine. The food seller was very eager to talk to us and gave information about the shrine before we met the shrine’s caretaker (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

The Guanyin shrine has red chanting books for the chanting group that visits once a week. Each book has a different collection of Buddhist scriptures but all of them have Chinese writings and corresponding Thai writings of phonetic Teochew next to each character (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

We set up a 360-degree camera to get full panoramic photos of each site we visited (photo courtesy of Kira Johansen).

May 26, 2023

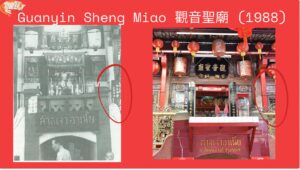

The second shrine we went to was also visited by Franke more than twenty years ago. It was Guanyin Shengmiao (觀音聖廟) or A Nia Keng Shrine (ศาลเจ้า อาเบี้ย pronounced Sanchao abia). The shrine was quite small and narrow in a busy alley full of pedestrians, motorcycles, food stalls, street vendors, and stray cats. At this second site, our group started to notice for the first time a stage situated across from the shrine. We found out from people around there that it was an opera stage for Guanyin. This opera stage shows up in other Guanyin shrines as well. The shrine hires an opera troupe to perform for the Guanyin on her birthdays and some people who succeeded in their prayers also come back to buy the Guanyin a gift of the whole night (or a couple of nights) of opera shows, or film screenings.

The caretaker of the shrine was a man in his 50s. He had just started a Facebook page of the shrine to record and share its history and stories, as he told us: “I’m worried about the future of the shrine after I’m gone.” He told us that the shrine was originally built by Chinese migrant families doing business around the area, but he did not know when or where in China they came from. Now, a couple of families have their kin as board members of the shrine. These people make decisions regarding the shrine. Again, the caretaker did not speak or understand any Mandarin.

At this Guanyin shrine, after we donated some money, we could write our names in the donor book. Then, the shrine caretaker would walk to the space under the drum which was high up near the ceiling. Under the drum, the caretaker would pull a long cloth string which was tied to a wooden stick. The wooden stick would hit the drum and make a loud and low “dum.” The caretaker hit the drum three times, making a “dum dum dum” sound every time a donation is made.

The front view of the Guanyin Shengmiao (觀音聖廟) (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

Donors tablet that was not there when Franke visited as it was added in the 90s (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

The shrine was next to a river and often flooded. The lifted-up level was used to help avoid flooding but now it became a place where the caretaker stayed during the night to prevent thieves hoping to steal old and valuable objects from the shrine (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

Comparing today’s photo with that of Franke’s. Slide by Kira Johansen. Republished with permission.

Visitors and worshippers can donate to have their names and family names written on candles, banners, and lamps. Lit every morning, a pair of candles depending on sizes can last from one to three months. The red banners are put up from Guanyin’s birthday until Vegan Food Festival, Che Festival, or เทศกาลกินเจ (Tessakan kin che) when they are replaced with yellow banners (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

May 27, 2023

Guanshiyin Pusa Gong (觀世音菩薩宮) or Guanyin shrine Wat Kanmatuyaram (ศาลเจ้าแม่กวนอิม วัดกันมาตุยาราม pronounced San chaomae kuan im wat kanmatuyaram) demonstrates the complicated and interlayered features of Buddhism in Thailand. The next site was a smaller shrine, the smallest of all the Guanyin shrines we visited, located next to a Theravāda Buddhist temple called Kannatuyaram Temple or Wat Kanmatuyaram. Here, according to the shrine caretaker, the Theravāda monks helped establish and support this place of worship.

The caretaker told us that this Guanyin shrine was founded by the Theravāda monk next door. A Singaporean student of a monk at the Kannatuyaram Temple gave him a statue of Guanyin. The statue was put somewhere in the temple for a while until one day, a visitor told the monk that “Mother Guanyin needs her own shrine” and as a deity, “she cannot be shrineless.” Hearing this, the monk asked around for people who would be familiar with the Chinese deity and her tradition. He then became a supervisor of the shrine’s construction and its caretaker afterwards. The current caretaker obtained her job because she is from a Chinese family, “can converse in Chinese” with foreign visitors and believers and understands Chinese traditions. She told us that because the shrine is financed by the visitors’ donation alone, when the donation was not enough, the Theravāda temple and its abbot would help with electricity and water bills, together with other supports it might need. In return, when the shrine did well with money, it would donate some to the Theravāda temple as well.

This shrine was the first site in our fieldwork where we encountered someone who could speak and understand Chinese. The shrine caretaker was a lady in her late fifties. She could speak Thai, Mandarin Chinese, Teochew dialect, and Guangdong dialect. Her parents came from southern China, and she was a babysitter in Hong Kong at some point in her life. That is how she came to speak many languages. However, she said that she does not read any Thai or Chinese. When we got to the shrine, she was with two other ladies who looked around the same age as her. Those two ladies came to help answer our questions as well.

The first interesting finding was that one of the ladies participates in the weekly chanting group. She said most members just memorize all the texts and when they chant, they do not really read anything from the book, despite holding it and looking as if they are reading it. She demonstrated how she pronounced the chanting in Teochew. We wondered how they would standardize the chanting to be in harmony, given that people may speak different dialects. The lady said that the group would ask every new member to read and see what adjustment to make in the pronunciation. Also, there are always some members of the temple community leading the chants so people could follow or slowly adjust to the standardized way of chanting. When asked where one would get the chanting books, the same lady pointed us to a publisher nearby. She said, “it’s very easy to obtain” as people would take the chanting books they like to any publisher/press and tell them that “I want a copy of this.” However, after following her instructions, we did not find the press she mentioned or a way to obtain the red chanting books.

Amidst the hot and humid weather, we moved on to Nanhai Guanyin Gong (南海觀音宮) or Nam Hai Guan Yim Nia Shrine (ศาลเจ้า หน่ำให้กวนอิมเนี้ยะ pronounced Sanchao namhai kuan im nia) as the second site of that day. It was the first shrine that the caretaker did not seem to be welcoming or willing to talk to us. He in fact told us “no photo” at the beginning. Then, after listening to us explaining our research and sharing purposes, he understood and told us that many people who are not related to the shrine at all came here and took photos of the altar with Guanyin, posted them online, and then asked for donations from online communities. The donations went into these con artists’ own pockets and not the shrine. The caretaker, after realizing we were friendly and had no such intention, became a completely different person who was very welcoming and happy to show us around.

He was relatively young compared to other caretakers we met—probably in his thirties. He lived at the shrine with his girlfriend, who studied and spoke Mandarin but she was not there at the time. They helped each other take care of the shrine and made devotional objects like gel candles that visitors could buy and offer to the Guanyin statue. From him, we learned that people sometimes leave their own Guanyin statues at the shrine for any time from three to seven days to one to nine months for consecrations before picking them up and continuing worshipping at home. “Some never came back to pick up,” he said while pointing to all sorts of dusty Guanyin statues on top of the cupboards nearby. He said some people gifted Guanyin statues to Guanyin, the main deity of the shrine, but some just find a place to get rid of their Guanyin statues.

This is the same case for animals that people deserted there. He told us that the stray cats living in the shrine were abandoned by some people. “What could I do? If I ignore them, they will die,” he said, so he took care of them. He told us that the government agency told him that they would send some vets to spay and neuter the cats but after a long wait, that has not happened. “This is the third or fourth time this cat gave birth already!”

We also learned a different account regarding the red chanting books. Here, the caretaker told us that we cannot buy the red books or obtain them anywhere because they were made specifically for and donated to the shrines.

A front view of the outer entrance to the Guanshiyin Pusa Gong (觀世音菩薩宮) (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

From left to right: Nanhai Guanyin Gong (南海觀音宮) caretaker, Kira Johansen, Professor Christoph Anderl, and Oliver Thomson. Professor Anderl looking at an old text presented by the shrine’s caretaker (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

A front view of the outer entrance of the Nanhai Guanyin Gong (南海觀音宮) (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat.

Stray cat family that lived in the Nanhai Guanyin Gong (南海觀音宮). Many shrines and temples in Thailand shoulder the burdens of stray animal caretaking (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

May 28, 2023

It was the first day that we took a taxi to our Guanyin sites instead of walking. These two sites were much farther from our hotel compared to the past sites. They are located on the western side of the Chao Phraya. Jianan Gong (建安宮) or Gian An Geng (ศาลเจ้า เกียนอันเกง pronounced Sanchao kian an keng) shrine gave a serene and more organized impression—this could be because it was in a quieter place and next to the river. It had received an award for a shrine with “the best architecture” and was visited by Princess Sirindhorn as well.

This was the first time that we were informed that contacting the shrine “through Facebook messenger” (and not email) before interviewing was mandatory. Otherwise, we could not have any of their time for questions. Taking photos inside the building is strictly prohibited. The shrine caretaker, standing behind a table full of pearl necklaces and other beautiful objects that visitors could buy and make offerings to Guanyin statues of their choices. Next to the caretaker, under the table, there was a woman who looked seems to be at the same age as the caretaker’s. She was tending to a sleeping baby. On the one hand, it seems that there is no time off for a caretaker and being a caretaker is not merely “working” as a caretaker but “being” a caretaker as one must work around-the-clock. On the other hand, being a caretaker seems to allow a person to bring their whole self (who they are and their family) to the workspace, meaning that, while the caretaker looks after a shrine, they and their family are taken care of in return by the shrine.

A man who was walking around the site told us that he and his family owned the shrine, and it is in the process of being renovated. We wondered how much change could be tracked from the beginning as taking photos was not allowed. If we revisit next time, we will not know what exactly has changed and how. This seemed to be what happened to the memories and histories of the Thai and where they come from as well.

Before we left, we met a young lady who seemed to be in her twenties. She bought a pearl necklace, candles, and incense for Guanyin. I asked her if she came here often. She said not really but “I started to come here more now.” When asked why, she told me that her mother was sick but then got better after she came to pray to Guanyin for her mother’s health so “I want to give back.” I wondered how she found out about the shrine, she said: “people told me this shrine is really working when it comes to health issue.”

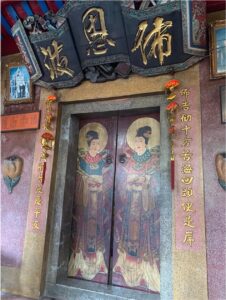

The next shrine was Nanpu Gong (南埔宮) or San chaomae a niao (ศาลเจ้า แม่อาเหนียว). It was a small shrine surrounded by a small community. On the way to the shrine, we each got free ice cream from the locals because it was the birthday of one of the locals living near the shrine. At the shrine, the caretaker was an older man—probably in his 80s. He was immensely proud of his job and the shrine. He closed the shrine doors so we could see the beautiful paintings of Guanyin on them. “People came here from all over the world to see these paintings” he said with a smile. There were other people around the shrine who helped the caretaker close the doors and answer our questions. We were told that two other caretakers before him passed away while sleeping because they cheated the shrine by stealing donation money so “it’s very important to be honest when working with Guanyin, otherwise she will take your life.” The caretaker was very scared of this and emphasized by telling this story to me twice.

At this shrine, when asked who often came here to pray, he said the people in this community, and he used the words “descendants of Mother Guanyin” to refer to the locals living near the shrine. The shrine caretaker and other locals who were with him told us that Guanyin likes watching movies so people who succeeded in asking for anything from Guanyin would come back to screen one Chinese, one western, and one Thai movie for her as a three-night package. For her birthday, they hired a Chinese opera troupe to give her a show for three nights. The opera performance would be performed on the stage facing the shrine. When the doors were closed, the (painted) Guanyin on the doors could directly watch the performances.

The shrine also owns incense pots given by King Rama V (1868—1910), some antique ceramic plates, and other objects in the dusty display cupboard. The caretaker told us that many people asked to buy some of the objects and offered a price, but he never dared to sell them, recounting the stories of the two previous shrine caretakers.

It was also at this shrine that we finally got some red chanting books. The caretakers said that we can donate money and take the red books, reminding us that he was not selling them. We learned how the shrine caretakers might not share the same beliefs, knowledge, and management philosophy. To an extent, it was as if each caretaker lived in their own sovereign areas. It would be fair to say that there is no generalized concept of what Chinese religious space in Bangkok is.

A front view of the entrance to the Jianan Gong (建安宮) or Sanchao Kian An Geng (ศาลเจ้า เกียนอันเกง). The shrine is right next to the Chao Phraya (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

A front view of the entrance to the Jianan Gong (建安宮) or Sanchao Kian An Geng (ศาลเจ้า เกียนอันเกง). The shrine is right next to the Chao Phraya (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

A view of the front entrance of the Nanpu Gong (南埔宮) or Sanchao Mae A Niao (ศาลเจ้า แม่อาเหนียว). The shrine caretaker proudly closed the doors and presented to us the beautiful paintings of Guanyin on both doors (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

A framed and printed news about the shrine on the wall inside of the Nanpu Gong (南埔宮) or Sanchao Mae A Niao (ศาลเจ้า แม่อาเหนียว) (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

May 29, 2023

The day off was very much needed for some repose. Over the past couple of days, I would hear the participants telling each other that they were quite tired, asking each other if they were tired, or candidly remarking that the other person looked exhausted. It was a well-deserved break, well deserved for everyone after days of physical and mental work. Some people decided to check out different bars, malls, palaces, and even more temples on their own and as a group. One group went to the Dhammakaya Temple (วัดพระธรรมกาย pronounced Wat phra Thamma kai) which was perceived as notorious and criticized intensely by some Thais in the past couple of years due to their controversial monetary scheme and architecture that “deviated” from “true” Buddhism. I do not remember how the temple settled the accusations and pacified the news but given that it still operates with many branches abroad, there must have been quite a number of supporters. On that day, I went home, which is around a two-hour drive with traffic from the hotel or forty-five minutes without traffic.

May 30, 2023

It was not clear whether the day off went by very quickly or the last day of field work arrived quicker. To our surprise, the cluster leaders decided to switch groups in a “mix-up” day. Our group got a new leader, Professor Ngar-sze Lau (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) while our regular leader, Prof. Anderl, led a different group. On that day, we planned to visit two Guanyin temples: 1. Niaoshi Si (鳥石寺) or ศาลเจ้า โอวเจียะหยี่อาเนี้ยเก็ง pronounced Sanchao O jia yi ania keng and 2. Guanyin Tang (觀音堂) or Chao Mae Kuan Im Shrine (โรงเจ กวนอิมตั้ง pronounced Rongche Kuanimtang).

At the first shrine, we were told that the owner of one of the most well-known wholesale malls often came there to pray and donate. The shrine caretaker lived there with his young child. He became a caretaker due to Guanyin’s help and her protection. Like other shrines, Guanyin is not the only deity but she is also surrounded by Buddha statues in different poses and other Chinese deities. Visitors could donate and write their names and years of birth on the provided papers. The shrine caretaker then rolled those papers and piled them up on the shelf at the back of the shrine. The caretaker told us that “we will pray and chant” those names to enhance their good luck, health, and wealth for the full year before burning the papers.

The second shrine, Guanyin Tang (觀音堂) or Rongche Kuanimtang, was a foundation that supported orphans. The nuns at the foundation were orphans who were raised and sent to school by an overseas Chinese couple. A happy incident occurred there when we got connected by the shrine nuns to a Mahāyāna temple called Foguangshan (佛光山). Foguangshan is a Mahāyāna temple in Taiwan and the one we were introduced to is one of its branches. The nuns made us a vegan lunch, arranged the transportation from their place to Foguangshan temple and then back to our hotel in Chinatown after the visit. The trip took around three hours of car ride in total, and the nuns paid for everything. On the way to the temple, the nuns called the taxi driver to ask if we liked the food and if we were doing all right.

During our visit to Foguangshan, I talked to one of the workers. She is Thai and used to identify herself as a Theravāda Buddhist until she worked at Foguangshan. “I started to be more Mahāyāna Buddhist,” she told me. The Foguangshan abbot came from Taiwan. He seemed to be kind, happy, attentive, and curious when conversing with us. He gave us books and told us about the construction of the temple in 2012–2013. After an hour at the temple, we all took the same taxi—which was waiting for us the whole time at the nuns’ request—back to Chinatown to continue working on our data input and photo organization.

Front view of the outer entrance of the Niaoshi Si (鳥石寺) or Sanchao Ojia ania keng ศาลเจ้าโอวเจียะหยี่อาเนี้ยเก็ง. On the left side was an opera stage to perform for Guanyin (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

Front view of an inner altar where people gifted jewelry and make-up to Guanyin when their prayer came true. On the left side is the shrine caretaker who assumed the role and dedicated himself to serving the deity after he was “helped by Guanyin” to win a lawsuit (photo courtesy of Oliver Thomson).

From left to right: the nun at the Guanyin Tang (觀音堂) or โรงเจ กวนอิมตั้ง (Rongche Kuanimtang) who arranged our travel and meeting with the Foguanshang abbot for us, Professor Ngar-sze Lau, Kira Johansen, and Oliver Thomson. (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

The front view of the outer entrance of the Guanyin Tang (觀音堂) or โรงเจ กวนอิมตั้ง (Rongche Kuanimtang) (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

From left to right: Saly Sirothphiphat, Kira Johansen, Taiwanese abbot of Foguangshan Temple in Thailand, Oliver Thomson, and Professor Ngar-sze Lau at Foguangshan Temple Thailand (photo courtesy of Ngar-sze Lau).

Kira Johansen arriving at Foguangshan (佛光山) Temple in Thailand (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

May 31, 2023

After days and nights of fieldwork and data input, the participants and leaders realized more time was needed to complete everything by the end of fieldwork. All groups decided to spend the entire day working with the information and data they had and not to add any more materials on top of that. The participants and leaders input data, organized photos, and prepared for the group presentation on the last day of the fieldwork program. Participants and leaders worked at the hotel lounge from 10am to 6pm and even later into the evening and night on that day.

Part of the presentation slides: a map showing visited Guanyin temples during the 2023 fieldwork. Slide by Oliver Thomson. Republished with permission.

June 1, 2023

It was another day of summarizing and organizing data. Our group went to a café for the third time, hoping to work on our data there. Unfortunately, of all three workers at the café, none knew how to use the espresso machine. Since it was our third time, they offered for us to use the espresso machine to make coffee by ourselves. We decided to resort to another small café with artisanal tea and coffee. This café was located opposite the first Guanyin shrine we went to on our first day of field work. I remembered somebody said how funny it was that we accidentally ended up next to where we started off.

In the evening, the FROGBEAR leaders and participants were invited to The Siam Society (สยามสมาคมในพระบรมราชูปถัมภ์ pronounced Sayam samakom nai pra borommarachupatham). We took an underground train (MRT) from Wat Mangkorn วัดมังกร station (meaning “Dragon Temple” in Thai) in Chinatown (Yaowarat) to Sukhumvit (สุขุมวิท) station. Located in downtown Bangkok and surrounded by towering buildings and skyscrapers, the Siam Society consisted of a couple of medium-height buildings in an older style, green lawns, and trees. It looked like its own realm.

Professors in our cluster group gave talks to FROGBEAR participants and an interested audience. Prof. Bingenheimer talked about Chinese religious space in Bangkok. Prof. Streiter and Dr. Yoann Goldin (Kaohsiung National University) presented their findings about cemetery tombstones and Chinese character tracing in Northern Thailand, Bangkok, and Taiwan. Dr. McBain then introduced the audience to technology use in fieldwork and the urgency of digital humanities especially in Thailand where seasonal flooding and humidity often ruin temple art.

After the gathering and lectures at the Siam Society, participants found themselves right behind a huge mall called Terminal 21 and across the street from Soi Cowboy (ซอยคาวบอย Soi khaoboi). The area is called Sukhumvit, and it is one of the most bustling night life areas in Bangkok. As a part of our research and fieldwork experience, the participants and some leaders decided to stay together while walking through Soi Cowboy, while the others had different opinions, did not walk through Soi Cowboy, and headed back to the hotel. I remember it was loud, colorful, and dizzying. Once everyone got to the other side of the alley, some went back to the hotel, while some had dinner around there.

The announcement board at The Siam Society (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

June 2, 2023

After breakfast at the hotel, participants travelled to Thammasat University. We concluded our official fieldwork in the same conference room in which we started off. Each group was scheduled to give a short presentation and fieldwork discovery to other participants and professors at Thammasat University after lunch. Preceding the sharing, Prof. Lau gave a presentation on ethnographic methodology, how to conduct ethnographic research, and problems researchers might encounter. The presentation was very insightful and relatable to the participants at that point, after being in the field for over a week. Then, Professor John Johnston (Thammasat University) presented on Thai Buddhism, its materiality, and its relationship with environmentalism. It was also an interesting and enriching topic. The professors’ interests and presentations throughout the program were remarkably diverse, informative, helpful, and most of all, needed.

After lunch at Thammasat University’s cafeteria next to the Chao Praya, our group came across a fortune teller shop. She did birth chart reading and palm reading. It was 300 THB for Thais and 500 THB for foreigners. Only two of us decided to get our futures read by the fortuneteller. Because she did not speak English, she used Google Translate to talk to non-Thai speakers. I noticed some inaccuracies in Google Translates’ reading. I wished I could know what was inaccurate in the fortune teller’s reading as well.

In the afternoon section, in which participants presented their findings, our group was assigned to go first. We showed what we found after following Franke’s footsteps. Two of the Guanyin temples we went to were visited and photographed by Franke. Then, after sharing our methods which included photographing, note taking, interviewing, and 360-degree filming, we focused on three recurrent themes in each Guanyin temple/shrine and in the caretakers’ interviews. One theme that constantly showed up was Guanyin’s relationship with the community. In kinship terms, the community members living around the shrine call her “mother” in the sense of a protector. One of the communities explicitly stated that they “are descendants of Mother Guanyin.” We also presented chanting books and chanting groups, both of which are found in all Guanyin shrines and temples. Our last point was about entertainment in the forms of opera and movie screenings for Guanyin. Different communities engaged in transactional relations with Guanyin. When someone received what they asked from the deity, they came back to screen movies and/or set up operas for many nights in return. These entertainments were also a form of gift for Guanyin on one of her three birthdays.

Guanyin shrines/temples connect and facilitate multi-layer relationships between people and communities, between individuals and between an individual and their community. Most significantly, some Guanyin shrines demonstrate the unique and ever-evolving relationship between Mahāyāna Buddhism and Theravāda Buddhism in Bangkok. For example, one Guanyin shrine had been sponsored and maintained by a Theravāda temple since its inception, and the other Guanyin shrine was blessed by Theravāda monks. The lines between different faith traditions are very blurry in Thai society. This complexity also reflects the difficulty of distinguishing between Thai and Chinese and defining what Thai-ness entails.

Professor Ngar-sze Lau presenting at Thammasat University (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

Participants from the Guanyin group took turns presenting their fieldwork findings at Thammasat University (photo courtesy of Christoph Anderl).

June 3, 2023

Professor Streiter and Dr. Goldin turned that quiet and unplanned morning into an intellectual and adventurous excursion. They lead five remaining participants to see a Muslim cemetery located right in the middle of Bangkok Chinatown where we respectfully looked at tombstones and the writings on them in hoping to get a better understanding of religious transmissions, movements, and adaptations in Thailand. The mosque’s name was Luang Go-cha Mosque (มัสยิดหลวงโกชา pronounced Matsayit luang ko cha)—Luang was a given title in past Thailand and Go-cha seemed to be a name. I had not realized that there is a Muslim cemetery within the Chinatown and even an active one. Next to the cemetery stood a cream-yellow colored mosque without dome architecture. The mosque caretaker told me that they would renovate the building soon, so it would not be the same when we revisit next time.

While other participants went to see tombstones and the arrangement of the cemetery, I conversed with the site’s caretaker. It was a casual and spontaneous conversation. Walking towards us, she said that the only concern was that she did not want women to step into the graveyard. “Men are ok,” she said. The lady, who seemed to be in her sixties told me how hard it used to be for not only for Muslims but also for Chinese to live and work in Thailand if they did not change their last names to Thai ones. Similar to other caretakers of Guanyin shrine, this caretaker of the Muslim cemetery lived on site in a small wooden house right next to the graveyard where her husband was buried.

After that, we all headed to a nearby café for coffee and to discuss what we had learned and what each person’s plan was after the fieldwork. Something we all agreed on was that fieldwork was not easy as it comprised many layers of labor, stakeholders, and technological collaboration. The fieldtrip ran for a suitable length of period and concluded at about the right time.

The Luang Go-cha Mosque (มัสยิดหลวงโกชา Matsayit luang ko cha) in Chinatown, Bangkok (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

The Luang Go-cha Mosque (มัสยิดหลวงโกชา Matsayit luang ko cha) cemetery (photo courtesy of Saly Sirothphiphat).

About the author: Saly Sirothphiphat is an MDiv student at Harvard Divinity School. She worked as a Chaplain Associate at Carleton College where she received her BA. Saly is currently an interfaith chaplain intern at MIT Addir and a Harvard Asia Center Thai Studies Program student assistant.

Click here for the original posting