By Rui Ding, University of British Columbia

On Tuesday, June 29, 2021, From the Ground Up: Buddhism and East Asian Religions (FROGBEAR) project held a workshop entitled “Metadata and How to Make It, for FROGBEAR and Beyond.” In this series of summer training sessions, nearly forty faculty and graduate students from different academic institutions all over the world joined the workshop virtually. Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions making on-site fieldwork impossible, the FROGBEAR workshops this summer provided online training opportunities for graduate students wishing to gain skills and knowledge in preparation for field visits in the future. The workshop introduced FROGBEAR field visit data previously collected from sites in East Asia, how to access and browse the FROGBEAR Database of Religious Sites in East Asia, how to collect metadata from fieldwork, and how to record metadata and make it accessible via the University of British Columbia (UBC)’s digital repository, cIRcle.

The workshop was divided into two sections. In the first part, the three speakers, Dr. Bruce Rusk (University of British Columbia), Tara Stephens-Kyte (University of British Columbia), and Anne Baycroft (University of Saskatchewan) shared their knowledge and experience of the database and the process of collecting data and creating and organizing data and metadata. In the second part, members of the workshop practiced inputting metadata by reviewing photos taken from fieldwork and discussed questions that came up during the process.

Bruce Rusk (University of British Columbia), Tara Stephens-Kyte (University of British Columbia), and Anne Baycroft (University of Saskatchewan). Screenshot courtesy of Carol Lee (UBC FROGBEAR). Republished with permission.

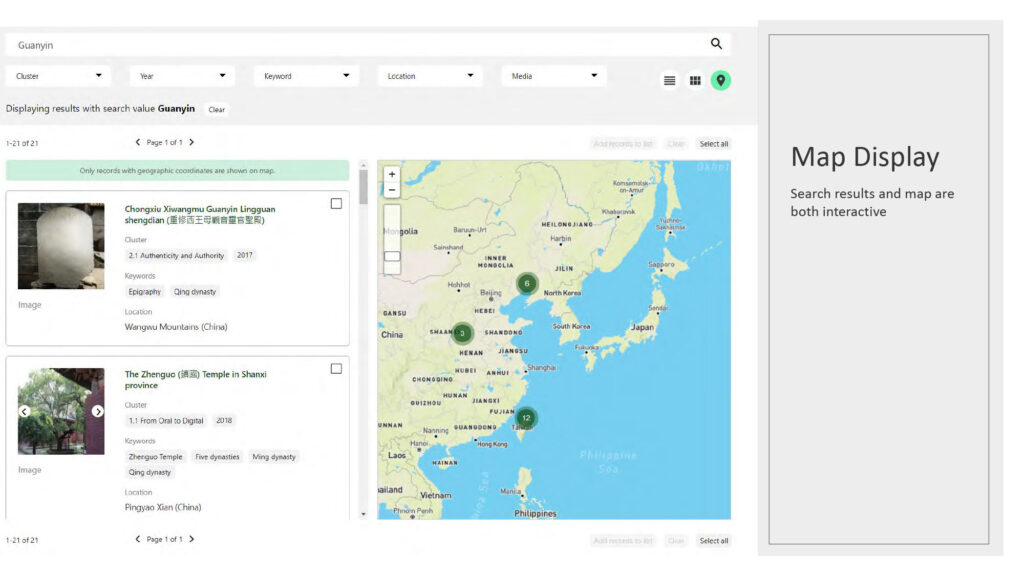

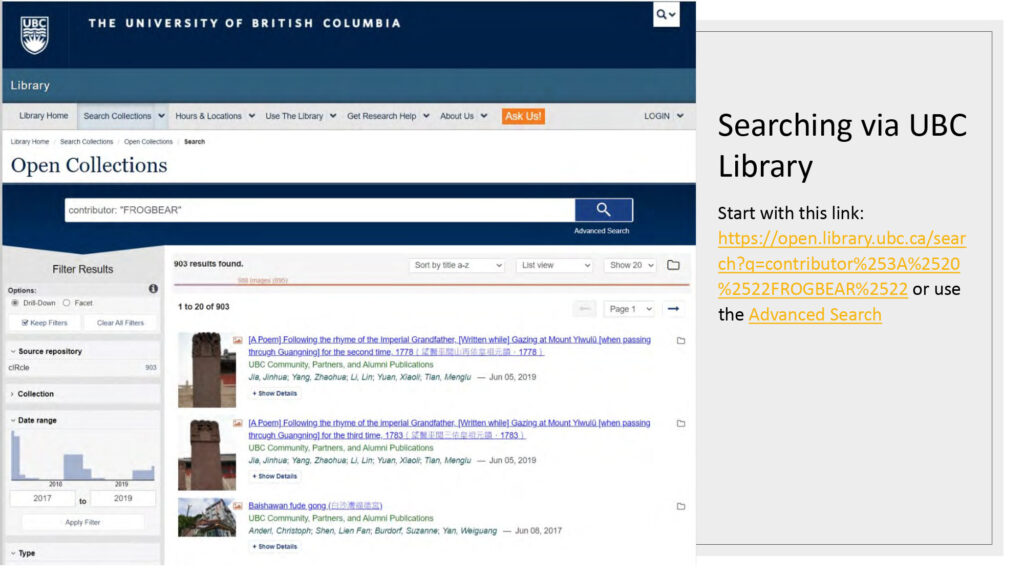

Dr. Bruce Rusk began with a brief introduction of the FROGBEAR project. The project started in 2016 and between 2017 and 2019 five research clusters visited sites in East Asia to collect data. Cluster visits in 2020 and 2021 were cancelled due to COVID-19 and rescheduled to 2022. Dr. Rusk then introduced FROGBEAR Field Visit Data in detail. During 2017–2019, 903 records were created, with 895 of them containing images and 124 containing videos, including drone footage and 3D photospheres. These data include records of sites, documents, inscriptions, and sculptures, presented in formats such as videos, images, texts and data files. All the data and metadata are open, public, and reusable, stored on UBC Library servers with unique, permanent identifiers for each record. There are two ways to access the collected data: FROGBEAR Database of Religious Sites in East Asia website (https://frogbear.org/app/), and UBC Library Open Collections (https://open.library.ubc.ca/), both of which have their own features for retrieving the materials. The FROGBEAR database only contains FROGBEAR material, and a user may sign up for an account to create and share customized lists. The search results can be easily filtered by FROGBEAR-specific categories such as cluster and region, as well as mapping geographical data. This website, however, may not be permanent. UBC Library Open Collections, on the other hand, provides access to a wide range of material from multiple UBC repositories of which the FROGBEAR data in cIRcle is a subset. A user can also conduct more complex searches by field, Boolean, and Application Programing Interface (API) searches, and sort their results. The data in cIRcle is retained indefinitely, but the Open Collections interface does not display geographical data like the dynamic map on the FROGBEAR Database.

Sample search result in FROGBEAR database with map display. Slide courtesy of Bruce Rusk. Republished with permission.

Sample search result in UBC Library Open Collections. Slide courtesy of Bruce Rusk. Republished with permission.

Beyond the basic information of a data record, there is metadata—“data about data,” to describe the time, location, author, and other information identifying the digital objects. Without metadata, electronic objects from fieldwork could not easily be searched or interpreted, even if it were accessible online. It is important to make sure that these metadata are entered by experts. During the Q & A session, Dr. Rusk answered questions about the possibility of establishing a channel for external comments and corrections on the database, the issue of user-friendliness, the training of experts entering the data within the cluster, and the long-term expectations for the database.

In the presentation by Tara Stephens-Kyte, she further explained the role of metadata and how it is organized. Stephens-Kyte explained what metadata is and why it is important, how field data becomes an item in the FROGBEAR database, what the metadata template for FROGBEAR looks like, and some tips and tools for good record creation. She started with an introduction of cIRcle, UBC’s open access digital repository for research and teaching material created by the UBC community and its partners. The FROGBEAR database is one of the many collections within cIRcle. What makes this data collection accessible is the metadata such as the information about the title, creator, description, location, and date. Most importantly, metadata must be accurate and systematic for people to find and use.

Landing page of cIRcle.

According to Stephens-Kyte, there are three types of metadata: descriptive, structural, and administrative. Descriptive metadata contains basic information about the resource title, author, and description, and is the most essential of the three. Structural metadata help users in discovering the data and how they relate to other data. Administrative metadata is for understanding how to manage the resource such as rights and permissions, including software requirements and copyrights. To ensure that the data meets the UBC Library’s mandate as an institutional repository, cIRcle offers core services to satisfy the different functions of the three metadata categories. Because the metadata is directly linked to our ability to search and find these resources, the Library applies metadata standards and quality controls which impact how content is accessed and displayed via UBC Library Open Collections and FROGBEAR database. A key component of structural data is preservation which is best supported by creating data files which use non-proprietary file formats where possible to ensure that the data is accessible in the long term. cIRcle also requires rights and permissions which support accessibility and promote re-use including a Creative Commons License, a Non-exclusive Distribution License and, where applicable, a Consent to Use of Image for photographs or recordings of people.

Metadata is important to understand because, as Stephen-Kyte explained, “the better the metadata, the better the experience.” Having better metadata makes further studies easier by enabling researchers to accurately search the database and discover materials and allows for more efficient analysis. It is especially important for materials where specific information such as geographic location or time period are not visible on the resource but are important context for the user. Metadata is organized by the following four approaches. The first is elements/fields which offer a basic building block of metadata description, including but not limited to title, abstract, and author. The second is rules or standards that must be followed in order to maintain consistency across records. The third is instructions for populating elements, such as the language used for specific topics in a given field. The use of controlled vocabularies, for example, can ensure consistent descriptions and discoverability by standardizing applied terminology.

Stephens-Kyte then presented a snapshot of the FROGBEAR metadata spreadsheet and explained the function of each part. She also mentioned what should be paid attention to when selecting the images of the sites, and things to notice when writing descriptions in the metadata. The data should be sufficiently clear for people who are unfamiliar with the subject material by providing relevant information that conveys the context and importance of a source. The description should be the part that researchers inputting data spend the most time on. It is the most challenging but essential part because it provides context for the content being viewed. The title is important as well because it affects how the item record will be displayed in cIRcle. Multiple files can be attached to the same title, especially for entries that are instances of the same site or object. The record title should be in English as much as possible, but Romanizations or Chinese characters can be added when applicable. Subject keywords describe what the content is about and although cIRcle does not have a strict rule on this, they recommend having at least 3–5 broad subjects, and ideally each FROGBEAR cluster should develop its own set of relevant keywords (i.e. controlled vocabulary). This way, people can easily identify which sources may be of interest and to then search for related materials. When recording the location of the subject, the geographic coordinates and the place name should be used to create more precise context for the source and allow it to be transferable to the FROGBEAR database mapping tool. At the end of the presentation, Stephens-Kyte pointed to some resources available for further reading, including a PowerPoint of a UBC Library Metadata Workshop, FROGBEAR Data Collection Instructions, the FROGBEAR database, and FROGBEAR materials in UBC Open Collections via cIRcle. In the Q & A session, the participants talked about utilizing API when using FROGBEAR data for their own research, and the possibility of curating an online exhibition of the data collection.

In the third presentation, Anne Baycroft, a PhD Candidate at the University of Saskatchewan, delivered a presentation on how the data was collected through fieldwork, with Jingshan Temple (經山寺) in China as an example. This presentation covered the process of photo and data collection in the field, how to create metadata using the cIRcle metadata template, and the results in the FROGBEAR database and UBC Library Open Collections.

The first thing Baycroft recommended was familiarity with background information relevant to the cluster, including its research area and goals, its research questions, and background readings. This helps prepare participants to understand the materials before arriving at the site. Second, she recommended working in pairs or small groups when doing the fieldwork, and assigning roles to each member such as photographer, note taker, translator, reader, and measurer. Third was to make a game plan by deciding what to photograph and how to take these photos. She recommended taking a walk through the space with your group to discuss what is important to document, the best approach to photographing them, and any potential barriers to data collection. Fourth was collecting location information including date, geographical coordinates, site name, object name, text name, and language. It may be helpful to use tools such as a digital compass for obtaining the geographical coordinates and checklists to ensure that all the information is filled out before leaving the site in the case that one cannot return to the same place to collect more data. Fifth, was to write detailed notes for each photograph including any unique information that may be useful for someone looking at the photos later on. Her sixth recommendation concerned translating the data collected in fieldwork into metadata. Baycroft highly recommended inputting the metadata into the spreadsheet template the same day the fieldwork was conducted, and working with group members to keep the information complete and accurate. She also recommended conferring with cluster leaders and members on “subject” terms and “description” sections. In the Q & A session, Baycroft answered questions about the video release of interviews in the fieldwork and some important issues concerning photographing within public spaces and fieldwork sites.

After the three presentations, the workshop moved on to a group exercise. Participants were divided into six groups using data collected from Matsunoo Taisha (松尾大社, Matsunoo Taisha/ Matsuo Taisha) in Kyoto, Fu Xi Temple in Taipei (台北伏羲八卦廟), and Mount Hiei (比叡山) on the border between Kyoto and Shiga Prefecture. With the provided photographs, notes, and spreadsheet templates, members practiced selecting the photos and inputting the data into metadata, working in groups in the breakout rooms. Group members took on the role of photograph selector, note taker, translator, and reporter.

After the group exercise, the reporter for each group shared how they worked together on the data, and their questions or concerns during the process. One of the participators asked about copyright issues when entering the description of the sites, especially when using external resources such as Wikipedia as an example, and Stephens-Kyte addressed the citation of external resource contributors as an answer. Another concern from group members practicing on Matsunoo Taisha was about the familiarity with the data, especially under the circumstance of lack of on-site fieldwork due to COVID-19. For participants working on Taipei Fu Xi Temple, writing a description under the guidance of the template was tricky, and extra efforts on the description were necessary. When doing data entry on Mount Hiei, some members found that choosing which system of Chinese characters (Traditional or Simplified Chinese Hanzi, or Japanese Kanji) became a question. Baycroft answered that system of character use can depend on the field location and historical context in which researchers are working. Dr. Rusk added when describing Chinese classics in Japan it may be appropriate to provide both Romanizations, Chinese and Japanese. Most often, English translation is the primary language, followed by Romanization and Chinese characters. There were also questions regarding the format of data entry and some practical issues in collecting data during the fieldwork, and Baycroft and Dr. Rusk introduced some useful tips when doing an on-site visit to address these issues.

Rui Ding is a PhD student in UBC whose research field lies in 14-19th century Chinese history, with a great interest in comprehensive historical research in and outside China, including Korea, Japan, the Ryukyu, while utilizing more research methodologies of global history, religion and material culture into her research.

Click here to the original posting