Student Reflection on the workshop Working with Objects and Manuscripts – Wongaksa Temple Museum, Korea

Jiayi Zhu

University of Chicago

December 13, 2021

On June 15, 2021 the Frogbear workshop, “Working with Objects and Manuscripts—Wongaksa Temple Museum, Korea,” was held on Zoom. Teachers and students from all parts of the world gathered together to carefully study the valuable Buddhist objects collected by Venerable Jeonggak at Wongaksa, Korea.

The workshop was divided into three sections. Before digging into the Wongaksa objects and manuscripts, Paul Copp (University of Chicago) gave a brief lecture and shared his thoughts on studying religious objects. Then, Venerable Jeonggak (Wongaksa Temple Museum, Central Sangha University) led a handling demonstration of pre-selected objects stored at Wongaksa Temple with live English translations by Youn-mi Kim (Ewha Womans University) and Seunghye Lee (Leeum Museum of Art). Last but not the least, all participants engaged in a discussion on these objects and beyond.

After the welcoming remarks made by Susan Andrews (Mount Allison University), Copp started his lecture titled, “Thinking About Working with Objects.” Coming from the perspective of studying material culture and religious practice, he encouraged all in the workshop to think about four questions: Why was the object made the way it was made? What kinds of uses was it made for? What was it made of? And how was it actually used?

Left: Susan Andrews (Mount Allison University); Right: Paul Copp (University of Chicago)

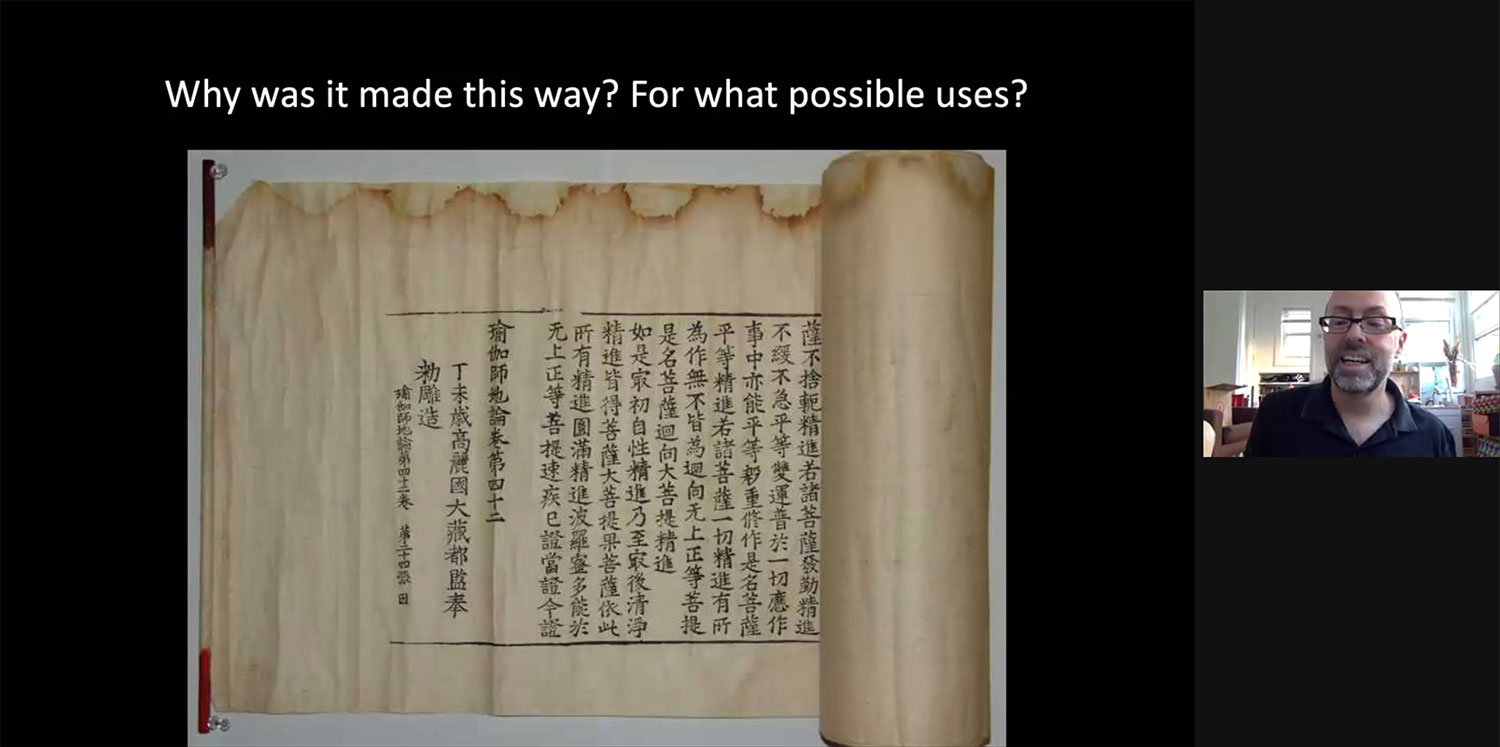

To answer these questions, he picked a few pieces from the Wongaksa Temple object list, as well as others from Dunhuang, as examples. Although he has not examined these objects in person, Copp suggested ways to read and analyze them. The first set of manuscripts he showed come with wide margins. One of these wide margins was left blank, while the other one is filled with commentary or other kinds of ancillary text. Depending on the content and when these characters were added, we may be able to find out more about the use and reading practices related to these manuscripts.

Discourse on the Stages of Concentration Practice (Yogâcārabhūmi-śāstra) from Wongaksa Temple collection

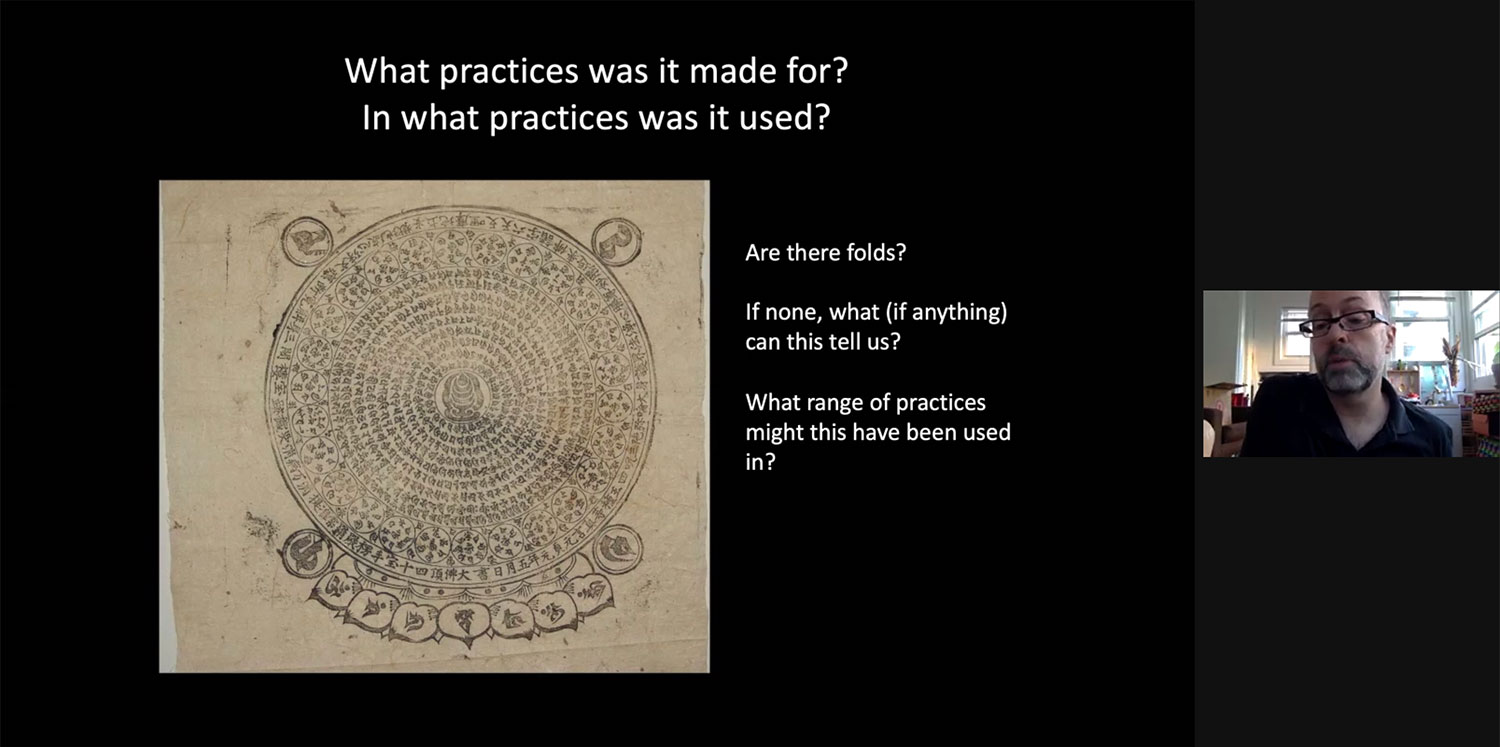

The second example was an incantation talisman from the object list. By observing the physical properties of the object, we can learn about what has been done to it and its potential use. For example, some other incantation talismans were made to be worn, and thus there would be creases on the paper, where they had been folded to be placed in a container. But there are no visible folds on this particular talisman. Was it made to be used as an amulet? Or made to be contemplated? These are some of the questions that could be asked.

An incantation talisman—mixed dhāraṇī including Great Usnīsa Dhāraṇī from Wongaksa Temple collection.

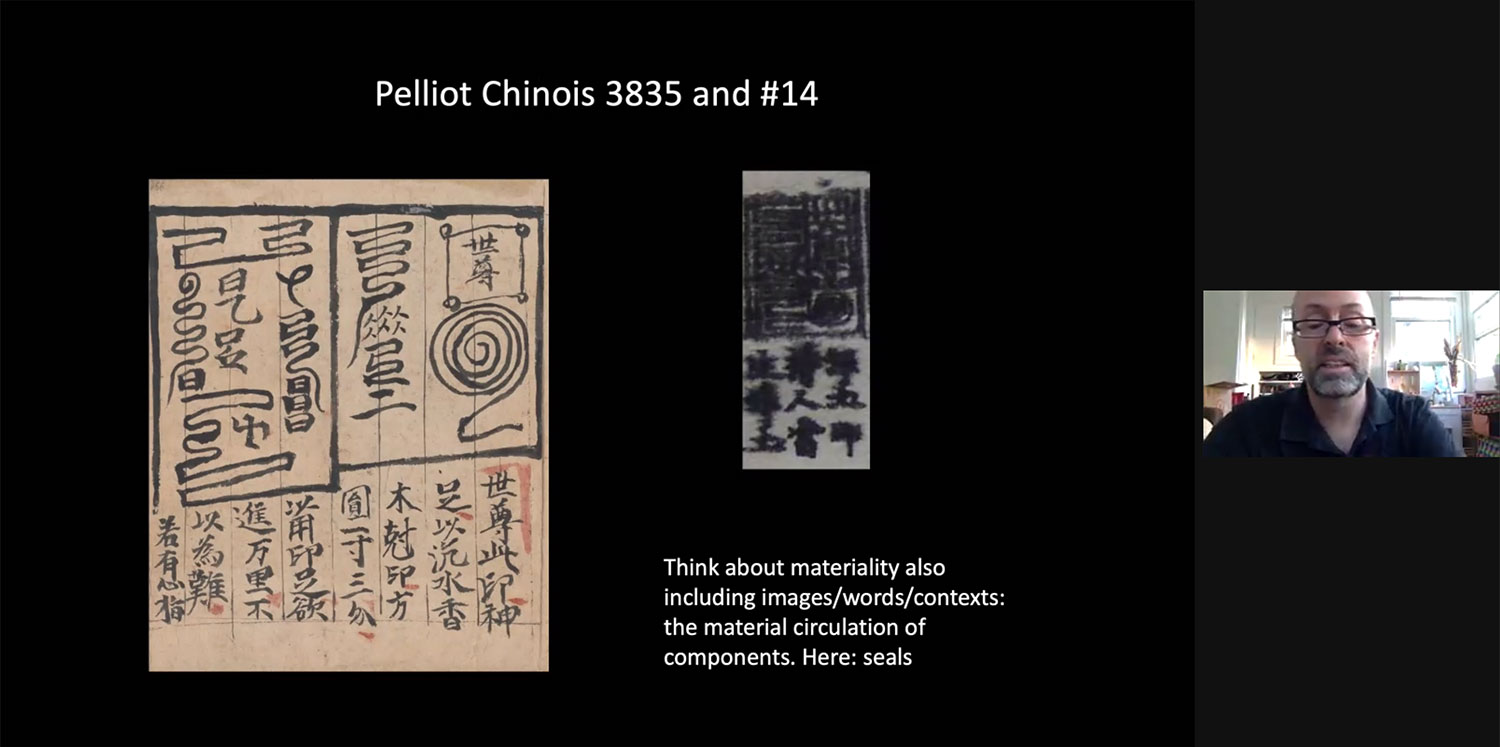

Thinking of these manuscripts at different levels—as text and as object—can help us understand the context of use better. The third example was a seal found on a printed ritual manual from Wongaksa. Copp suggested ways that, through comparison with similar objects from Dunhuang, we might start to analyze and learn about the circulation of the components that made up this object. A similar seal is found on a Dunhuang manuscript (Pelliot Chinois 3835). As a seal, they look alike; but as for other components around them on the paper, they are drastically different. This suggests the ways that such components might have been mixed and matched within different ritual contexts. We can also begin to think about the vast geographical scale of these borrowings, in this case spanning Korea and Dunhuang. Objects travelled with people when they moved around places so we have to consider how components shift in the world of material circulation and how it ends up in a different context.

Left: Pelliot Chinois 3835; Right: mixed dhāraṇī and Buddhist talismans from Wongaksa Temple collection.

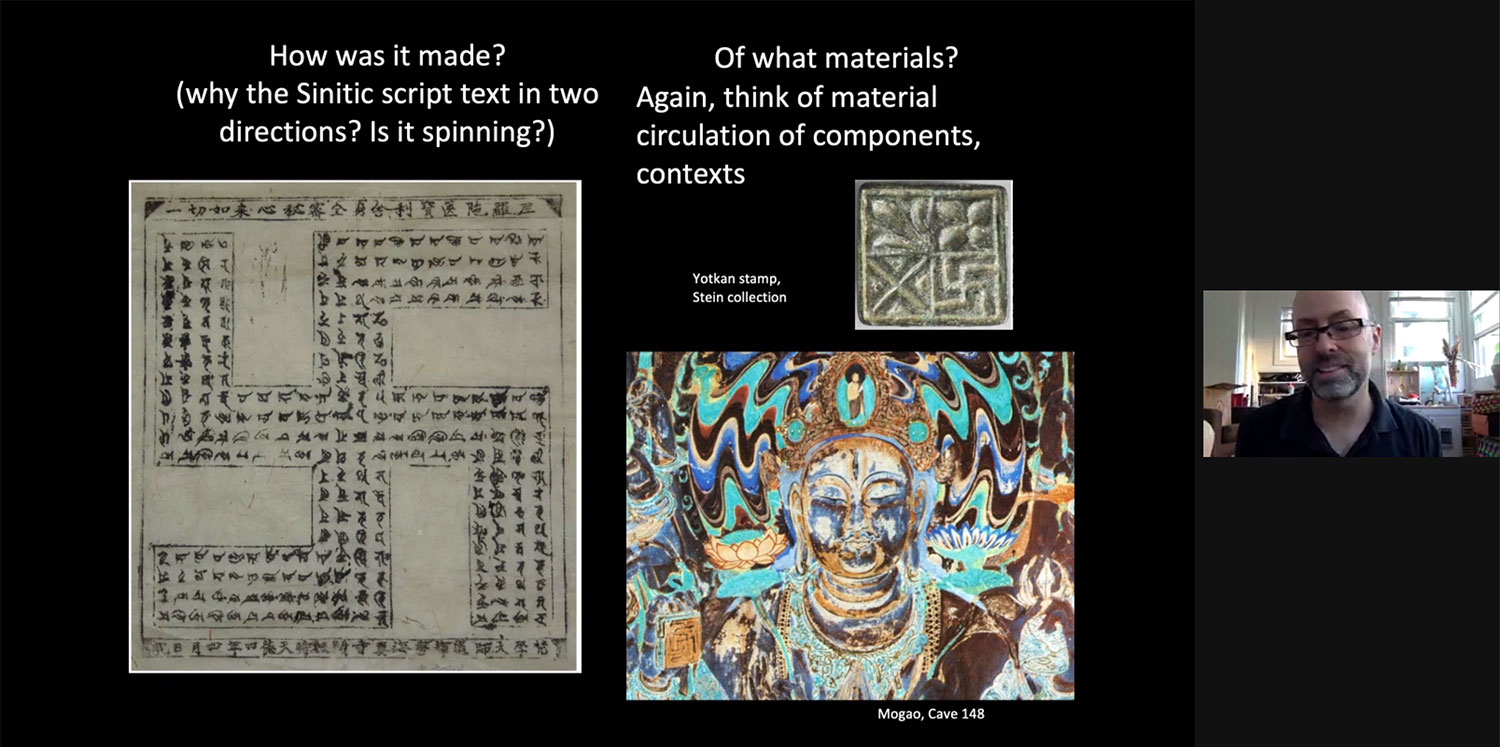

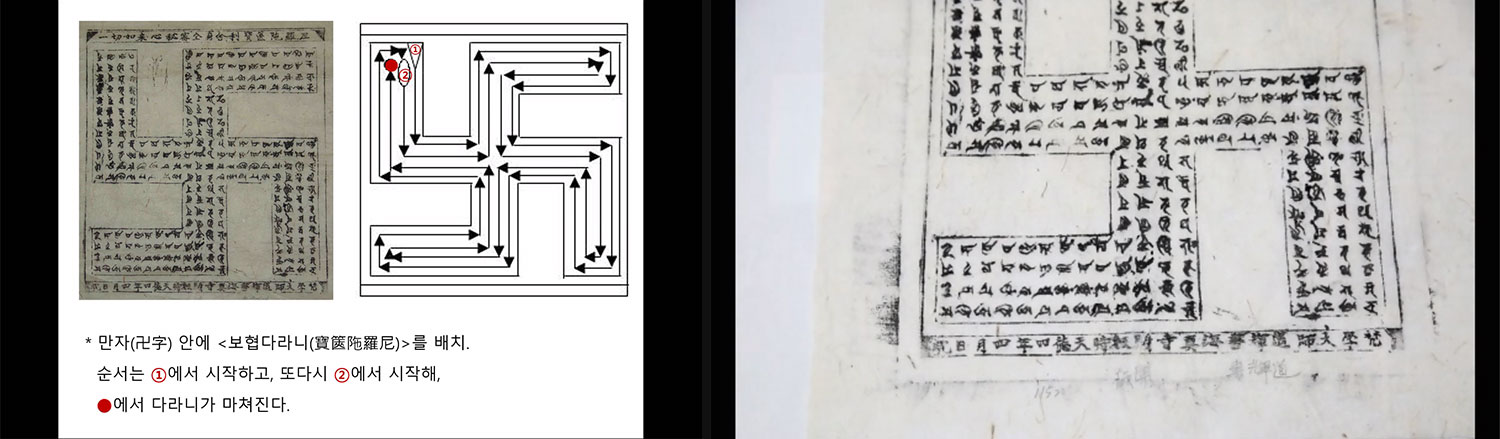

The last example of the lecture was a dhāraṇī print of a text in Indic script within a swastika shape, again from the Wongaksa collection. The colophon in Chinese on the top reads from left to right, but the one on the bottom reads from right to left. Copp wondered if it would be useful to imagine that, given the nature of the central figure, this might indicate that the figure was meant to be seen as spinning. He intended this a thought-experiment to get students thinking in terms of the entirety of an object, materially, visually, and textually.

Left: Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Precious Casket Seal of the Concealed Complete-body Relics of the Essence of All Tathāgatas from Wongaksa Temple collection. Top: Yotkan stamp from Stein collection. Bottom: mural detail from Mogao Cave 148.

Then, we moved on to the Wongaksa objects, selected from a collection of over 2,000 pieces. The eighteen Buddhist sutras, dhāraṇī prints, Buddhist paintings, and crafts on display that day, according to Venerable Jeonggak, are among the most valuable and significant objects he collected.

From left to right: Youn-mi Kim (Ewha Womans University), Venerable Jeonggak (Wongaksa Temple Museum, Central Sangha University), and Seunghye Lee (Leeum Museum of Art).

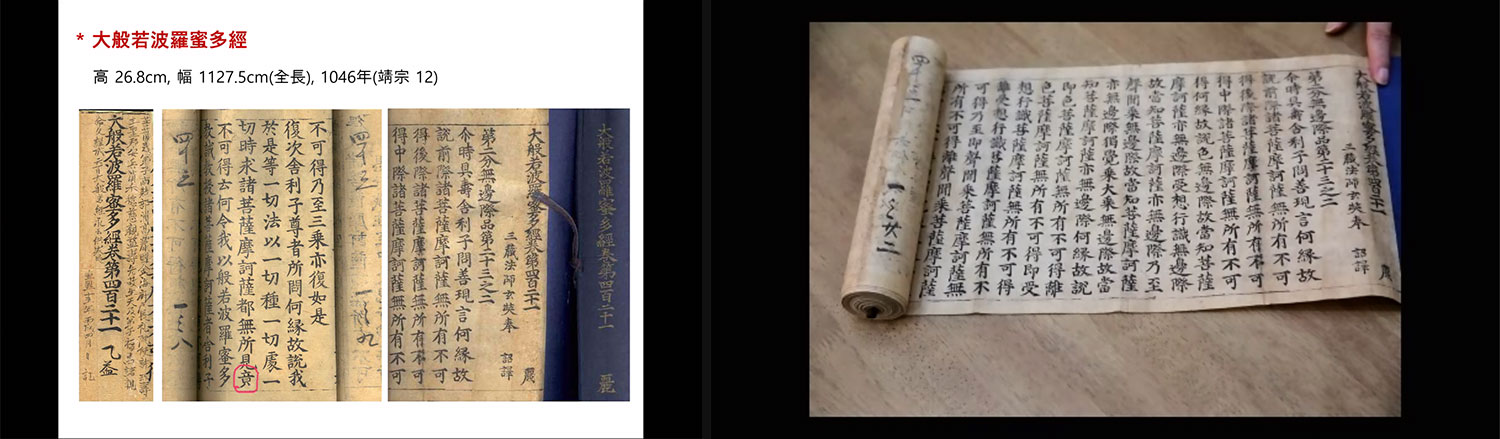

The first group of objects are printed Buddhist sutras. Venerable Jeonggak began with a scroll from the first edition of the Korean Buddhist canon. Among the surviving scrolls printed from the first edition, twenty are designated as National Treasure and sixteen are designated as Treasure by the Korean government. The scroll we saw is one of the Treasures. Venerable Jeonggak gave a brief introduction on the Korean canon and its relation to the Chinese canon. This version of the Korean canon is similar to the Chinese Kaibao canon, but unlike the Kaibao canon, there is no publication record. This particular scroll was printed before 1046, as indicated by the donor inscription towards the end. He also showed us one scroll from the second edition of the Korean Buddhist canon, printed from the original thirteenth century woodblocks that are still preserved in Haeinsa in Korea.

Mahāprajñāpāramitā sutra, printed before 1046.

Discourse on the Stages of Concentration Practice (Yogâcārabhūmi-śāstra), printed from Tripitaka Koreana woodblocks carved in 1247.

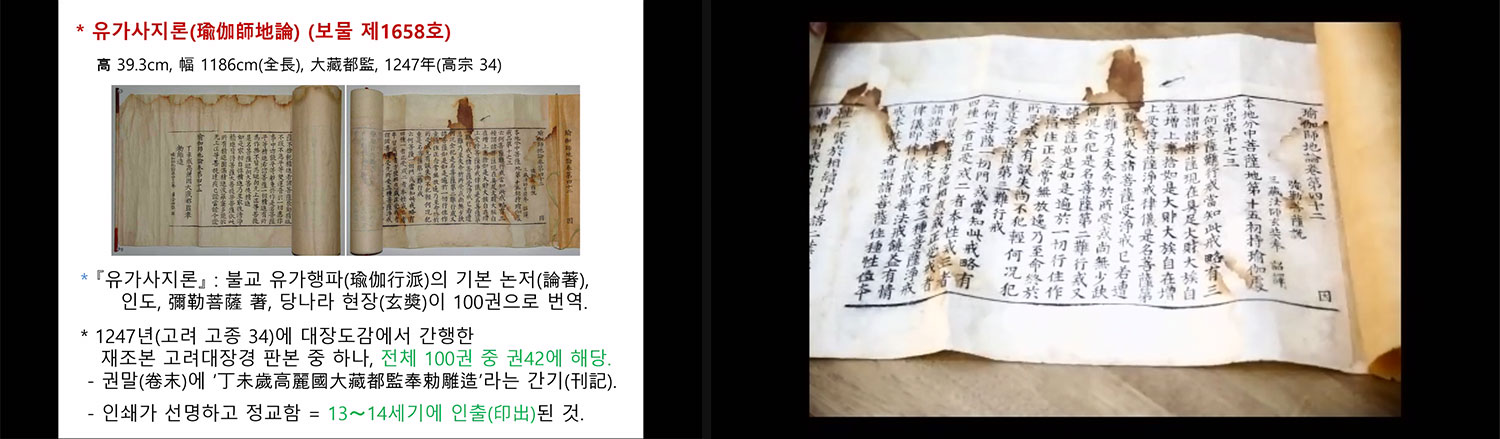

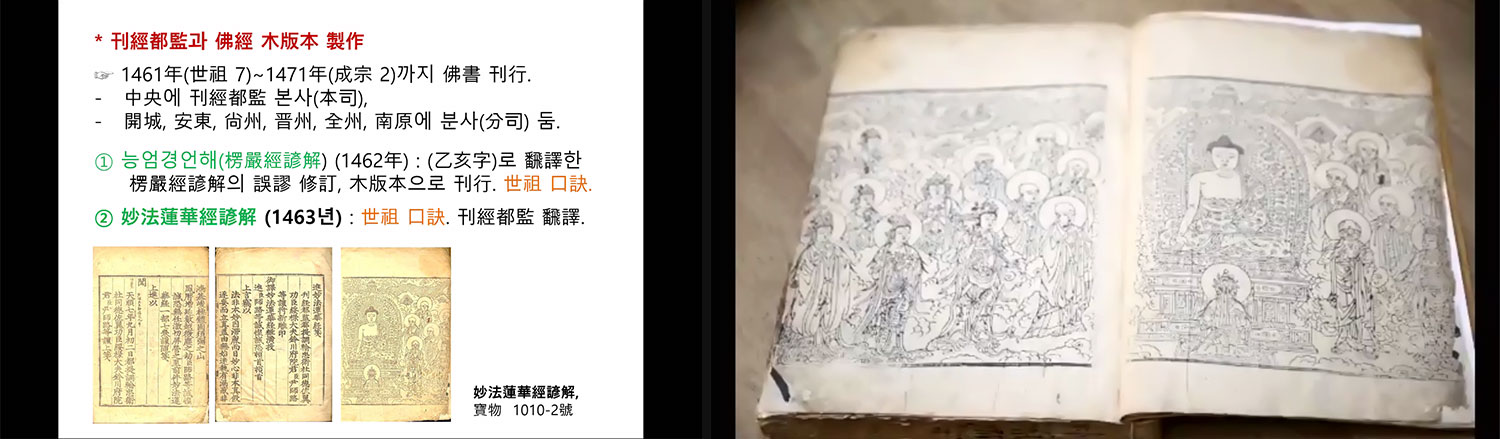

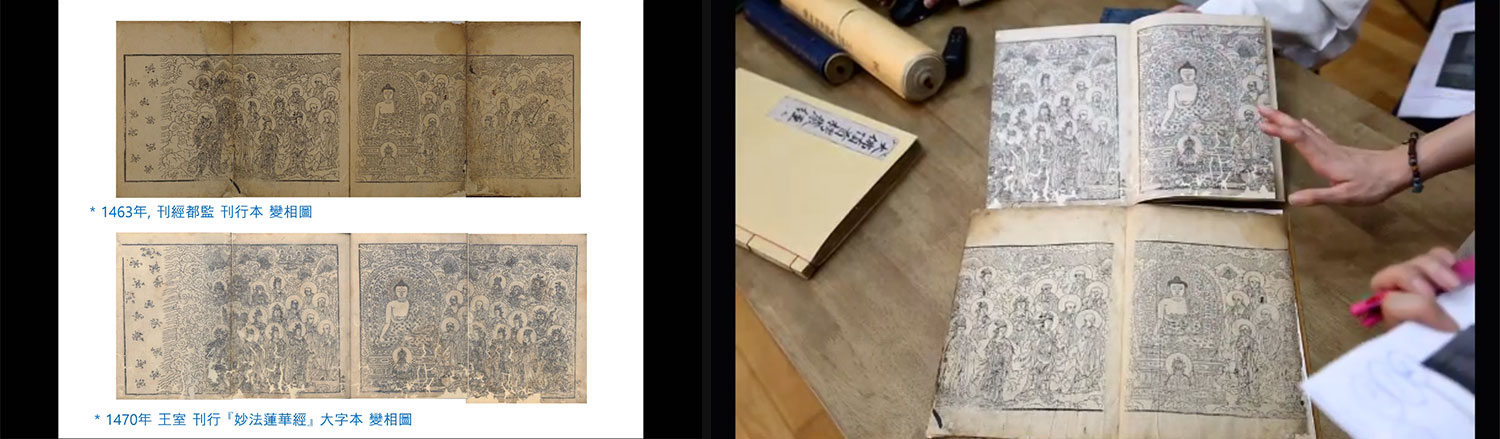

Following this, Venerable Jeonggak displayed several other sutras also designated as Treasures. Among which was the Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Dharma printed in 1463 by Gan’gyeongdogam. The sutra we looked at was the edited version before the official publication. It used a special kind of paper made from mulberry mixed with straw. The most important part of this printed sutra is its frontispiece—the scene of the Sakyamuni Buddha preaching at Vulture Peak. The prototype of this illustration first appeared in a Chinese Buddhist scripture published in 1417 during the Ming dynasty. Then, the illustration was found on a Korean print from 1459. The same illustration seen in the Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Dharma from 1463 appears in a later version of the sutra from 1470. Interestingly, Buddhist paintings from the Joseon dynasty were also largely inspired by this particular illustration.

Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Dharma, dated 1463, published by Gan’gyeongdogam.

Comparison of Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Dharma 1463 version (top) and 1470 version (bottom).

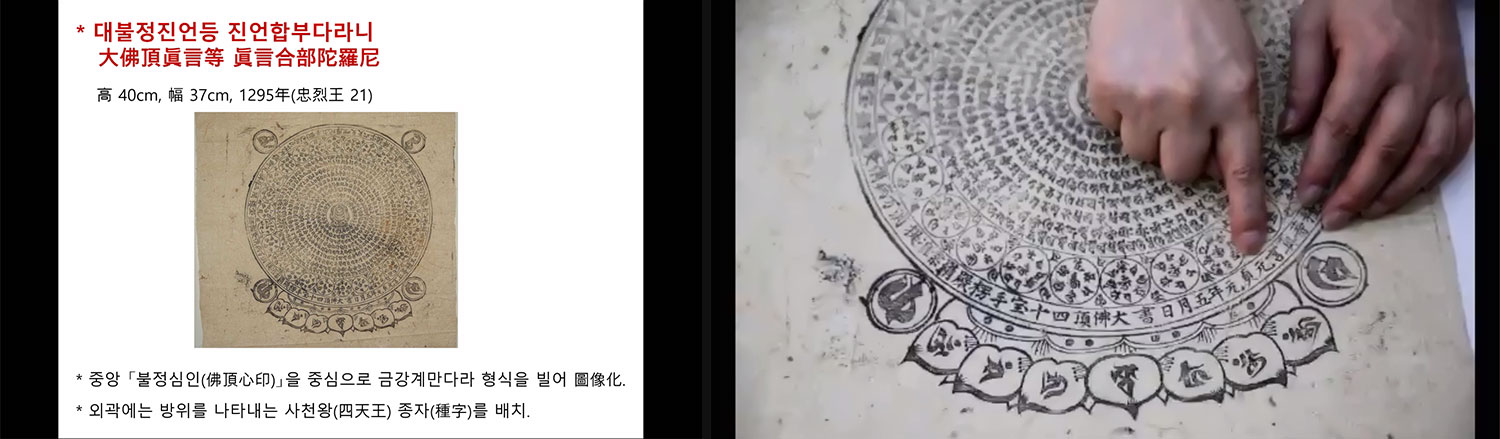

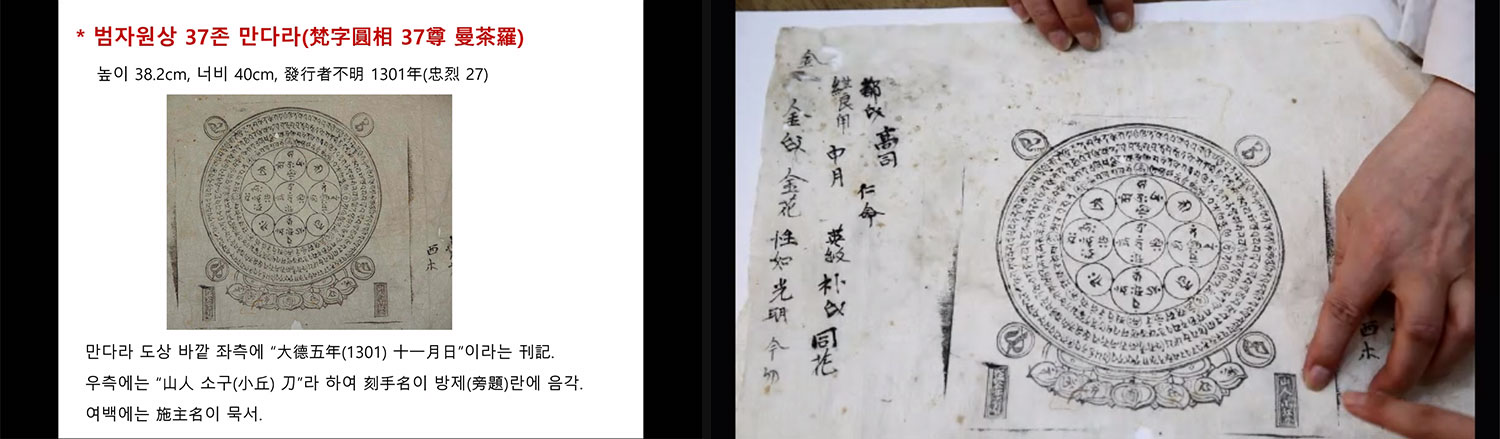

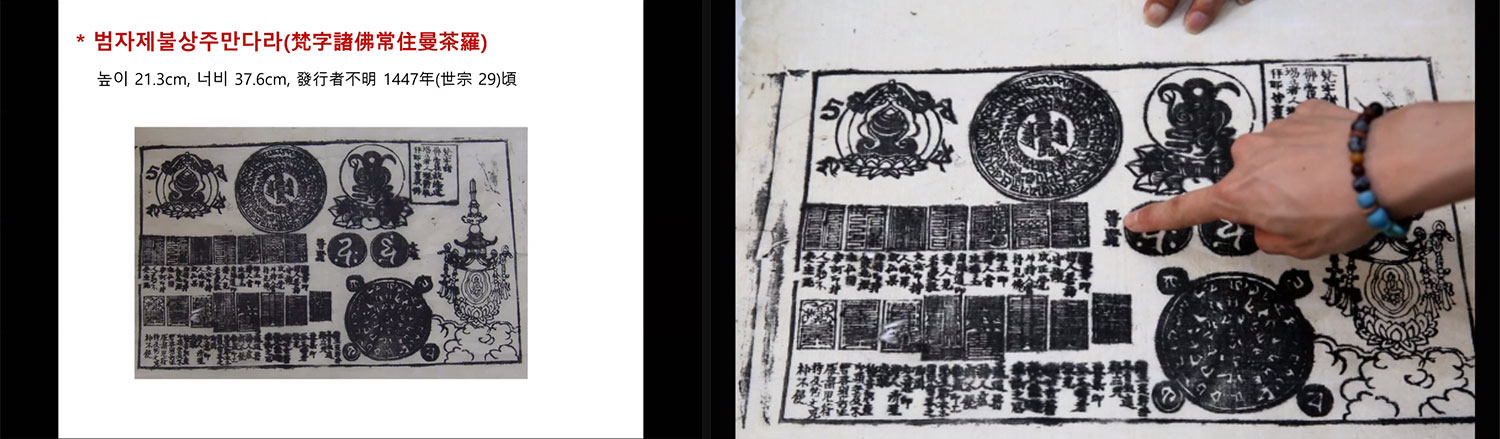

The second group of objects we examined was the dhāraṇī print. Dhāraṇī is a kind of incantation or spell that encapsulates the essence of a Buddhist teaching. The first print Venerable Jeonggak introduced was the Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Precious Casket Seal of the Concealed Complete-body Relics of the Essence of All Tathāgatas in a unique swastika shape, which was the last example Copp used in his lecture. This 1152 print has its text starting from the upper left corner and proceeding through the margin of the swastika. The next two dhāraṇī were printed in 1295 and 1301 in a circular shape, with four characters representing the Four Heavenly Kings at the corners attached to the main circle. The 1301 print was probably enshrined in a Buddhist statue, as there were names handwritten to the right of the print, which might have been those of the donors. Lastly, Venerable Jeonggak showed the print Copp used as his third example. On this 1447 print, there is a variety of woodblock printed Buddha seals, dhāraṇī seals, and Siddham letters.

Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Precious Casket Seal of the Concealed Complete-body Relics of the Essence of All Tathāgatas, dated 1152.

Mixed dhāraṇī including Great Usnisa Dhāraṇī, dated 1295.

Mixed dhāraṇī with the Diamond Realm Mandala in the center, dated 1301.

Mixed dhāraṇī and Buddhist talismans, dated 1447.

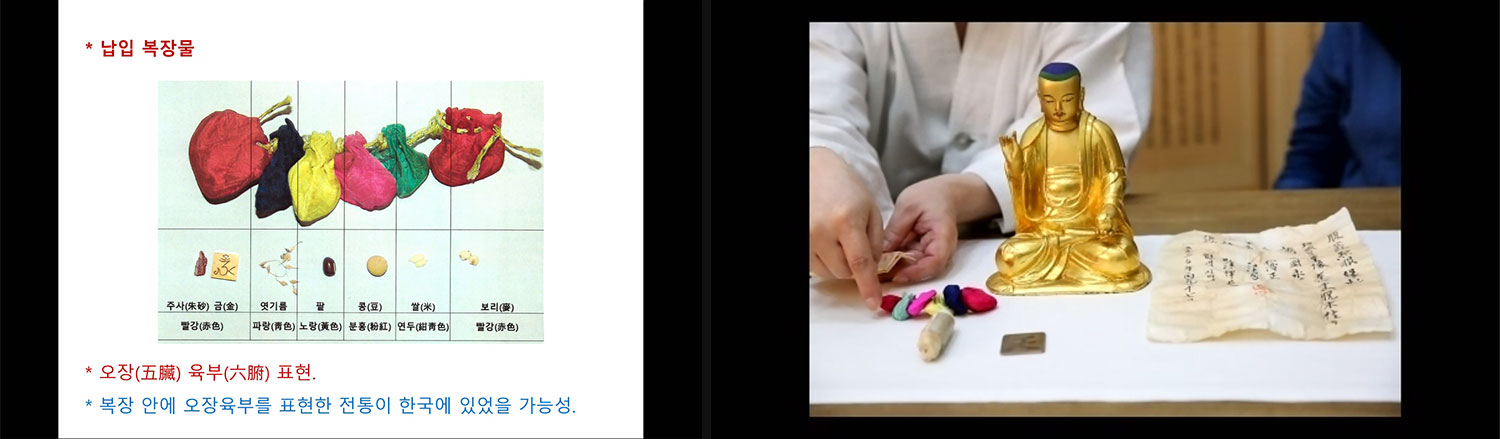

After a short break, the workshop moved on to examine three-dimensional objects. The first object was a gilded Kṣitigarbha statue dated between the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, based on the style of his elongated upper body. The gilded part can peel off as time goes by, therefore, practitioners will regild at later times. Further, the enshrined objects in this statue, called pokchang in Korean, indicate that this statue was restored in the year 1977. Pokchang contains written materials and textile objects. The textile objects include materials like cinnabar, gold, fermented barley, red bean, and rice. Venerable Jeonggak mentioned that they might have symbolized the human body and intestines.

Ksitigarbha bodhisattva from the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century, and consecrated objects within it from 1977.

Next was a set of small terracotta pagodas. According to the Pure Light Dhāraṇī Sutra, one would receive merit from writing its dhāraṇīs and enshrining them into pagodas. Venerable Jeonggak showed us the holes at the bottom of the small pagodas, which means the practice prescribed by the sutra might have been carried out here. But none of the dhāraṇī inscription is intact. These examples are likely from the Unified Silla period, as the ones from the Goryeo period do not bear any holes.

Miniature terracotta pagodas, Unified Silla dynasty.

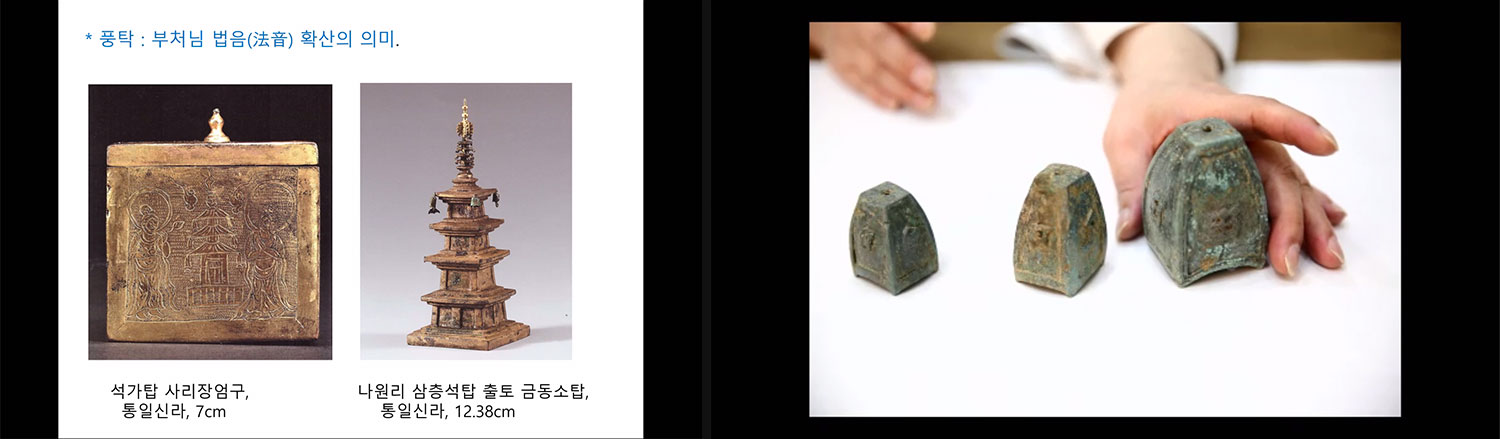

Following this, we saw a set of three wind bells or wind chimes from the Goryeo period made of bronze, with a Siddham letter inscribed on each side of the bells. The bells symbolize the spread of the Buddha’s words to enlighten people. Venerable Jeonggak showed some pictures of how the wind chimes were attached to the actual pagodas. The three examples are different in size, indicating that they might have been hung at different levels of a pagoda.

Bronze wind bells, Goryeo dynasty.

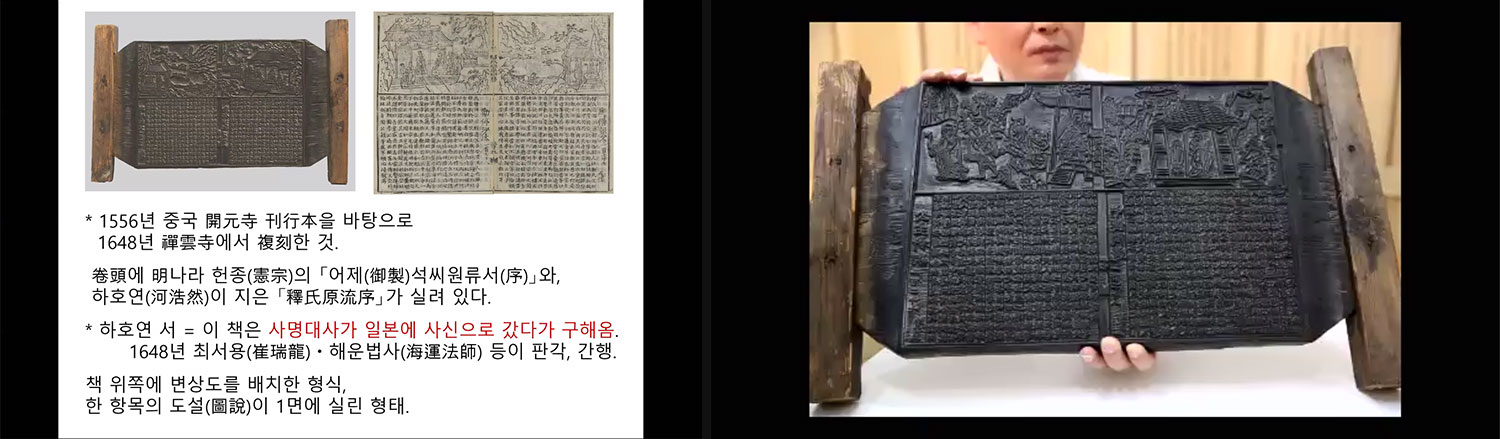

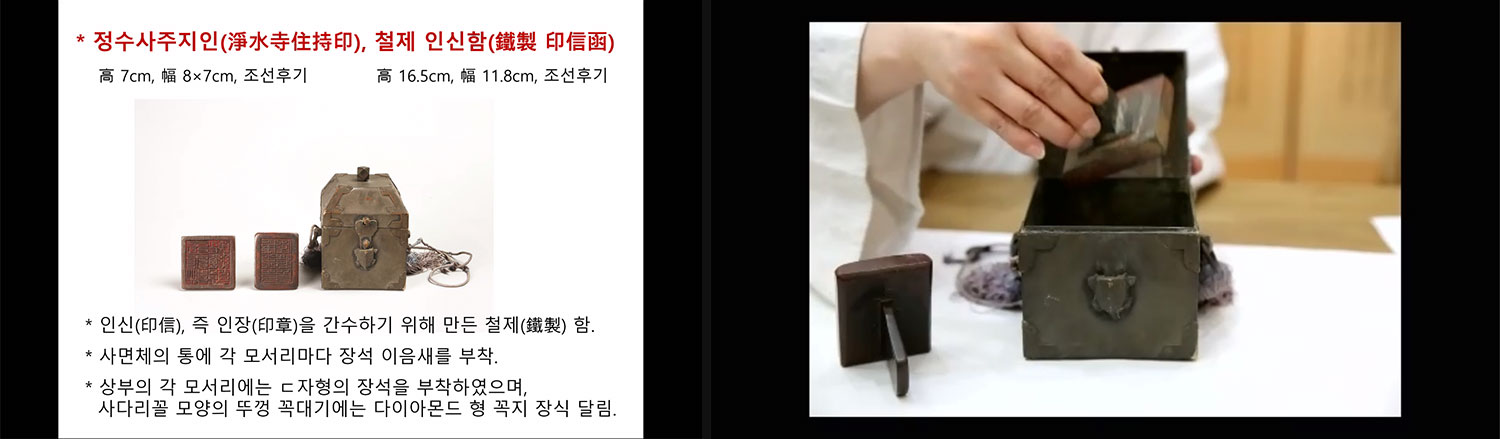

Venerable Jeonggak also picked a woodblock from his collection as an example to show how the prints we saw earlier were made. The cost of the sophisticated craftsmanship would be exorbitant even today. The iron case housing two copper seals is also the product of careful craftsmanship. The seal belonged to the abbot of Jeongsusa. It looks like the ones bestowed upon high governmental officials, and its comparatively large size indicates the prominence of Jeongsusa in the late Joseon.

Woodblock of Seokssiwollyu, dated 1569.

Iron case and seals and of the abbot of Jeongsusa, late Joseon period.

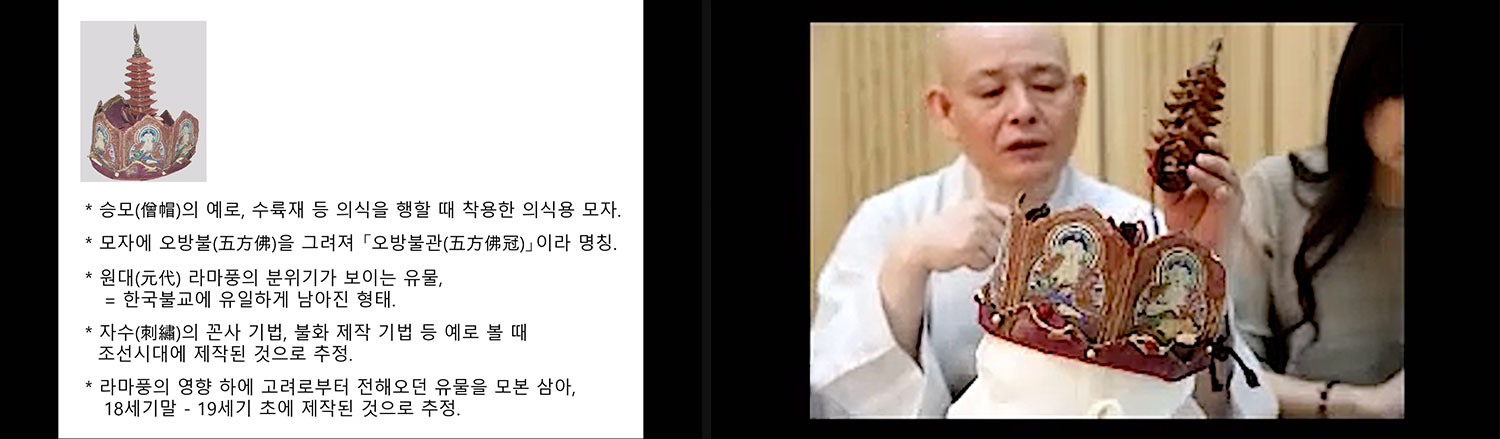

The last demonstration we had was on a Buddhist crown bearing the five directional Buddhas from the late Joseon dynasty. Based on Chinese Buddhist paintings, this kind of Buddhist crown was probably used at rituals like the Water Land Ritual. In the center is a miniature pagoda made of paper; the Five Buddhas were painted on paper and then pasted to the sides of the hat. According to Venerable Jeonggak, it utilized techniques such as twisted threads and is worth further examination.

Monk’s hat for ceremony (hat with Five Directional Buddhas), late Joseon.

After viewing all of these objects, the floor was opened up for general discussion. Some questions were inquiries on details of the shown objects. Copp asked where the case with two seals were stored. Although the original context was lost, Venerable Jeonggak referred to the portraits of abbots from Joseon dynasty as a clue—the seal case is usually placed on the armrest next to the abbot as the symbol of authority. A workshop participant asked about the material used for carving woodblocks. The example shown was made of Korean pear tree as it is a harder type of wood according to Venerable Jeonggak.

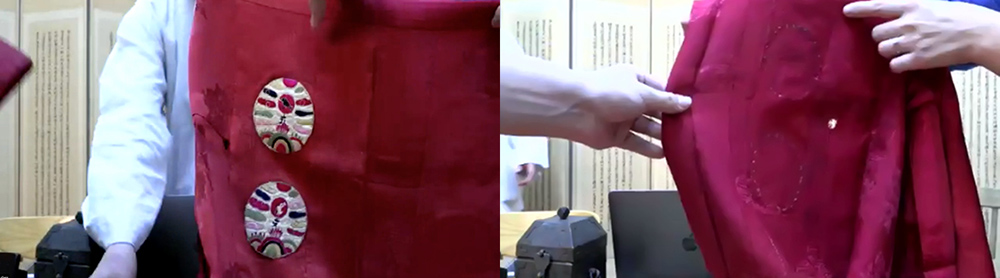

Participants in the workshop were also curious about the context of using these objects, especially the Buddhist crown with the Five Buddhas. One of the questions was on why the Buddhas were pasted on instead of painted directly on the fabric. Venerable Jeonggak explained that the painted Buddhas were made to be detachable because then the textile could be washed without ruining the paintings. Other objects like his monk’s robe also have these kinds of removable components for the same practical reason. Another participant asked about how the paper pagoda and the Buddhist crown were incorporated into one set of ritual objects. Venerable Jeonggak replied that he once encountered a Chinese Water Land Assembly painting depicting such a crown, and this might have been one singular case of a Buddhist crown inspired by such Chinese tradition.

Left: embroidered patches on the front of the monk’s robe; Right: backside stitching of the patches on the inside of the robe.

The workshop concluded with Venerable Jeonggak’s remarks. He first thanked all the participants from around the world for coming to this online workshop and welcomed everyone to visit and study these objects in person in the future. He also thanked everyone that made this workshop possible. Kim, Lee, and Venerable Jeonggak remained online for a while after the workshop officially ended to present the painting of Avalokiteśvara in White Robe dated to 1880, and other additional artefacts from the object list for those who were interested.

Jiayi Zhu is a PhD student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilization at the University of Chicago. She is interested in medieval Buddhist ritual and art in East Asia. For her doctoral research, she plans to examine the use of dhāraṇī in local practices across China, Korea and Japan.

Click here to see the original post